New archaeological research has disproved one of the world’s most famous historical narratives: the environmental cautionary tale that claimed the ancient civilization of Easter Island collapsed in the Pacific Ocean because the islanders destroyed its ecosystem.

The research instead reveals how that civilization thrived through tenacity and innovation, until it was ultimately destroyed not by native Polynesian environmental disaster, but by European aggression, disease and exploitation.

The archaeological research shows that the island’s population remained stable at around 3,000 until the arrival of often violent and disease-causing European whalers, slavers and colonizers in the mid-19th century.

The population’s ability to survive at a stable level until then appears to be due to advanced horticultural techniques that the islanders used to maximize food production.

The new research, conducted by scientists from three US universities and an indigenous scientist on Easter Island, shows that early islanders identified areas of the island as suitable for intensive horticulture and then used advanced techniques to increase crop yields.

Their use of these techniques (rock mulching and rock gardening) implies an advanced knowledge of horticultural agronomy – technologies they almost certainly brought with them to the island, along with relevant plant foods, when they first arrived there around 1200 AD.

In rock mulching there was first the realization that the available natural soils did not have the required nutrients, and then there was another realization that the missing nutrients could be added to the soil by grinding rocks and mixing the resulting rock dust with the soil to mix.

Rock gardening helped regulate soil surface temperature, wind speed and humidity. By scattering small rocks and stones around their gardens, and by planting crops in the small spaces between them, they provided plants with better protection from wind and windblown sea salt and also helped maintain a more constant temperature and humidity. The civilization on Easter Island was Polynesian, as were the cultures of hundreds of other islands scattered across the Pacific Ocean.

Most of these islands are very remote and are often hundreds of kilometers apart. But what makes Easter Island unique is that it is perhaps the most remote and isolated place ever inhabited by people in ancient and medieval times.

It is located 3,500 kilometers from the nearest major landmass, South America, and 1,850 kilometers from the nearest other country. Linguistic, genetic, and other evidence suggests that the Polynesians who colonized Easter Island around 1200 AD came from the Gambier Islands, about 1,700 miles away.

The Polynesians were among the world’s first great sailors. Using 20-metre catamarans, they used the stars, the sun, the wind, wave and swell directions – and knowledge of seabirds and tiny bioluminescent marine microorganisms – to enable them to navigate with very considerable accuracy.

The Polynesian explorers who discovered and settled Easter Island almost certainly did not know the place existed. Like many ancient Polynesian explorer-settlers, they would have ventured into the unknown without knowing if they would ever find land.

Because Easter Island is about 1,700 miles from the Gambier Islands, they would have reached or exceeded the limits of their return range. Some long-distance expeditions of Polynesian explorers and settlers must have occasionally ended in fatal failure – when they failed to find new land and starved to death on the high seas.

Although the small islands scattered throughout the Polynesian Pacific Ocean make up only about 0.2% of that portion of the total area of the Pacific Ocean, Polynesian sailors were more adept at finding small patches of unknown land than any other people on Earth.

By using their knowledge of wave and swell phenomena, telltale land-based bioluminescent microorganisms and seabird behavior, they were able to increase their chances of finding previously unknown islands. And with the help of gigantic double-hulled canoe catamarans, they were able to carry enough food and fresh water.

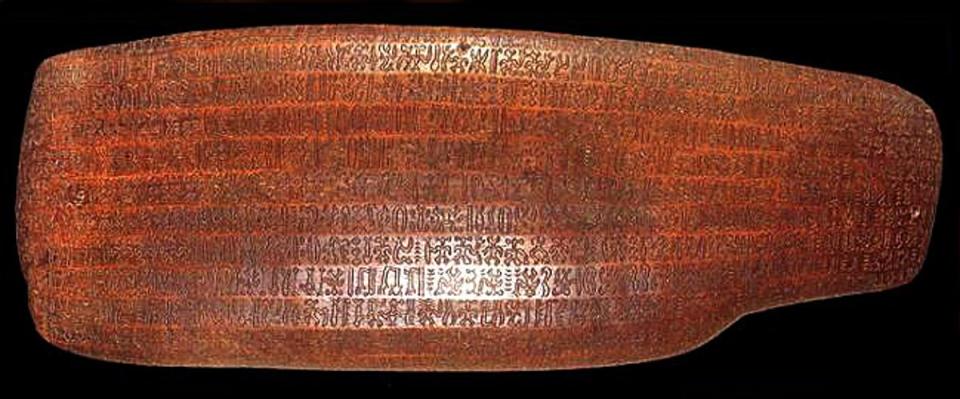

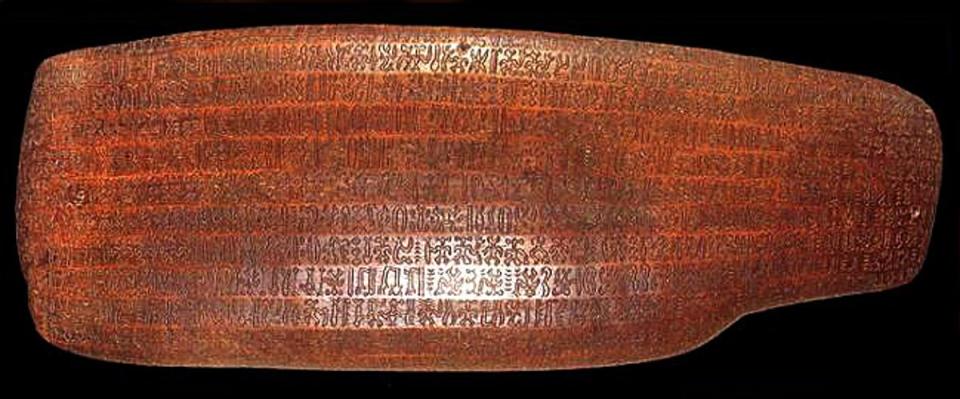

They also brought with them the Polynesian tradition of ancestor worship and the associated phenomenon of carving statues (representing those ancestors).

The globally famous giant stone statues of Easter Island are the world’s best-known Polynesian monumental works of art. Although only about 600 completed Easter Island statues survive intact or in a fragmentary state today, it is likely that several thousand were made over the centuries – from ‘small’ statues of five tons to gigantic statues of nine meters and 86 tons.

It is likely that the first Easter Islanders arrived as a group of about a hundred people on about six ocean-going canoe-catamarans. Around 1300, the naturally growing population reached the island’s carrying capacity: about 3,000 people.

The island’s palm trees were not suitable for making large seagoing vessels, leaving the residents completely isolated. Over the next 500 years, they cut down most of the palms, turned the top 1% of the land into mulched food gardens, and used another 10% of the land to grow yams, bananas, and sugar cane.

All crop varieties had been imported, probably during that first voyage of 1200 AD. They had also imported chickens and a kind of rat; species that provided proteins for centuries to come.

It took enormous courage, skill and determination to discover and settle Easter Island – and centuries of hard work and dedication to maintain a stable, successful society.

But that society and most of its members were unable to survive the arrival of disease-bearing, violent Europeans in the mid-1800s; many died of European diseases and others were kidnapped and enslaved.

European (including British) businessmen took control of the land and turned it into a huge farm, populated by 50,000 sheep. Ultimately, it was those sheep that destroyed Easter Island’s remaining environment – and it was disease and cruel slavery that killed most of Easter Island’s residents.

By the 1860s, 95% of Easter Island’s Polynesian population was dead or forced to leave. But over the past 130 years, the indigenous population has recovered and now makes up 45% of the 7,800 inhabitants of the island, also known as Rapa Nui – and part of Chile since 1888.

The groundbreaking study, which refutes the indigenous ecocide theory, was published yesterday by Scientific progresswas co-authored by American archaeologists Dylan Davis (Columbia University), Robert DiNapoli (Binghamton University) and Terry Hunt (University of Arizona) – and by Gina Pakarati, an indigenous independent researcher living on Easter Island.