When you buy from our articles through links, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

The BepiColombo spacecraft may have only made quick flybys of Mercury, but it is already helping to unravel mysteries surrounding the planet closest to the sun.

In 2026, a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Agency (JAXA) will orbit Mercury, the smallest planet in the solar system. To do that, however, the spacecraft must first fly past Mercury, Venus and Earth several times. Fortunately, these flybys prove invaluable to science.

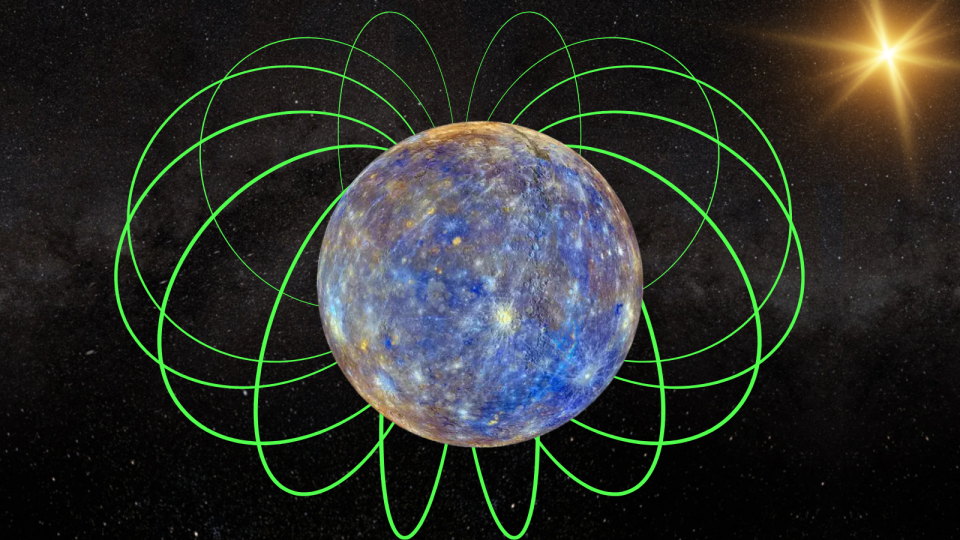

During a flyby of Mercury in June 2023, BepiColombo encountered several features of the planet’s magnetic field. This field forms a protective magnetic bubble around Mercury, shielding the planet from charged particles in the solar wind, similar to how Earth’s magnetosphere protects our planet – but scientists are curious as to why this small inner planet’s magnetic field is much weaker than that of us.

Because Mercury is much closer to the sun than Earth – Mercury is an average distance of 58 million kilometers from the sun, while Earth is about 150 million kilometers away – its magnetic bubble experiences a much more intense pounding from the solar wind.

One of BepiColombo’s main tasks will be to investigate this interaction and the properties of Mercury’s magnetic field. The spacecraft will build a dynamic double image of the space environment around Mercury by splitting into several units: the ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO).

Related: The BepiColombo probe captures stunning images of Mercury in the closest flyby yet

Fast flybys of Mercury are helping scientists determine BepiColombo’s final orbit, but these passes have also given operators tantalizing hints about the kind of science the mission will yield when it is actually in place. The six planned flybys will also provide glimpses of Mercury that would not be possible from orbit.

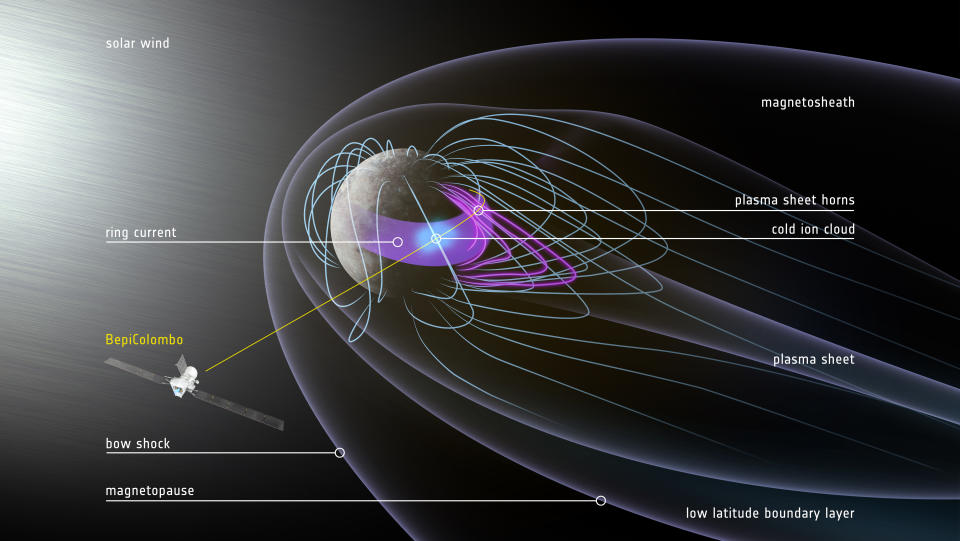

“These flybys are fast; we passed through Mercury’s magnetosphere in about 30 minutes, from sunset to sunrise and at closest approach from just 235 km above the planet’s surface,” said Lina Hadid, of the Laboratoire de Physique des Plasmas in Paris Observatory, said in a statement. “We sampled the type of particles, how hot they are and how they move, which allowed us to clearly map the magnetic landscape over this short period.”

Surprises in Mercury’s magnetic bubble

Hadid and colleagues conducted their research using BepiColombo’s Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment (MPPE) suite of instruments, which were active during the June 2023 flyby (the third of six encounters between the spacecraft and its target planet).

The team combined the data collected by MPPE with computer models, revealing the origins of interacting particles and the characteristics of Mercury’s magnetic bubble.

‘We saw expected structures such as the ‘shock’ boundary between the free-flowing solar wind and the magnetosphere, and we also passed the ‘horns’ flanking the plasma sheet, a region of hotter, denser electrically charged gas flowing outward like a tail toward away from the sun,” Hadid said. “But we also had some surprises.”

Using BepiColombo’s Mass Spectrum Analyzer, which is specifically designed for the complex space environment around Mercury, the team saw a turbulent boundary where the solar wind meets the planet’s magnetic field. This was indicated by a region of turbulent plasma with the highest energies ever seen on Mercury.

‘We have also observed energetic hot ions near the equatorial plane and at low latitude trapped in the magnetosphere, and we think the only way to explain this is by a ring current, a partial or a complete ring, but this is an area that discussed a lot,” Hadid added.

Ring currents like the ones she describes are generated when charged particles are captured by magnetic bubbles around planets. Earth’s ring current is at an altitude of tens of thousands of kilometers above the surface. Mercury’s magnetosphere is more compressed against its surface than Earth’s, meaning it’s a mystery how the magnetic bubble can trap particles a few hundred kilometers above the planet, as the team saw.

The team also studied the direct interaction between charged particles in the solar wind and plasma around Mercury and BepiColombo itself. This process is complicated by the fact that as the spacecraft points toward the sun it heats and cools, and heavier charged particles called ions cannot be detected because BepiColombo becomes electrically charged and repels them.

However, when BepiColombo moves into Mercury’s shadow, cool ions become detectable in a sea of plasma. This allowed BepiColombo to see ions of the elements oxygen, sodium and potassium around Mercury. The team believes these particles originated from the small planet’s surface and were launched into space by meteorite impacts or solar wind bombardments.

“It is as if we are suddenly seeing the surface composition ‘explode’ in 3D through the planet’s very thin atmosphere, known as the exosphere,” MPPE instrument leader Dominique Delcourt of the Laboratoire de Physique des Plasmas said in the statement. “It’s really exciting to see the connection between the planet’s surface and the plasma environment.”

RELATED STORIES:

— BepiColombo spacecraft swings by Venus on long path to Mercury

– Bow thruster problems delay the arrival of the BepiColombo probe Mercury until November 2026

— Watch Mercury roll by in a stunning sequence from the BepiColombo probe (video)

“During this rare dawn-to-dusk movement through the large-scale structure of Mercury’s magnetosphere, we tasted the promise of future discoveries,” Go Murakami, JAXA’s BepiColombo project scientist, said in the statement.

These findings come from the June 2023 flyby, meaning scientists still have data collected from last month’s Mercury flyby to analyze. After this, BepiColombo will make its last two flybys of Mercury, on December 1 and January 8, 2025 respectively.