In a rehearsal room under a railway arch in south-east London, a gang builds a barricade from old ladders and chairs. Actress Debbie Chazen’s Mrs. Gertz waves a kitchen utensil when she sees the ranks of police. “I need a bigger rolling pin!” She quickly turns into one of the officers, just as Jez Unwin, in a Jewish prayer shawl, turns into a blackshirt.

‘I think it’s time to join in! Irish and Jewish, black and white and young and old,” shouts Mairaid from Sha Dessi. This is followed by chants of “The y-ds, the y-ds, we have to get rid of the y-ds” and “Oy falls! The Cossacks are coming!”

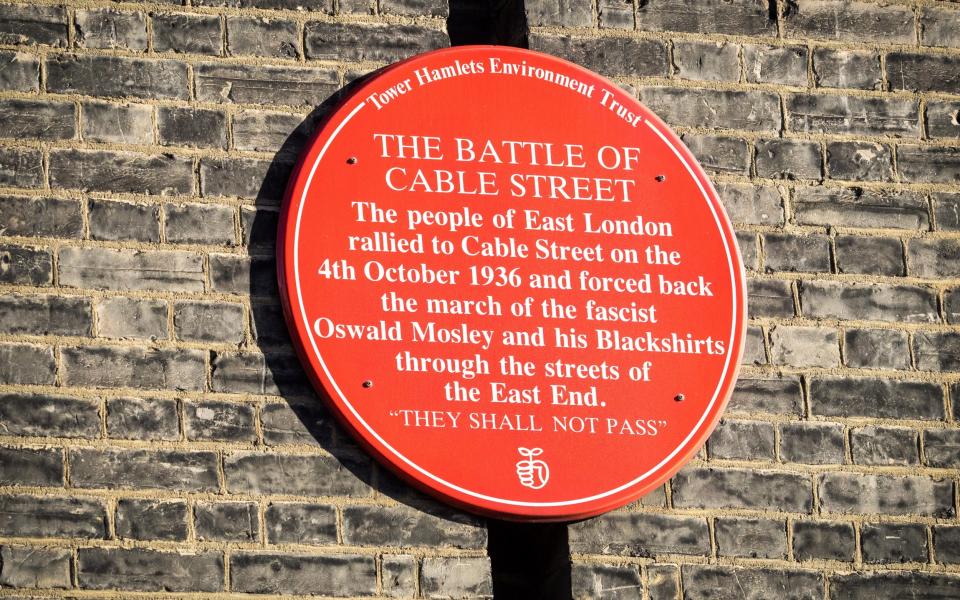

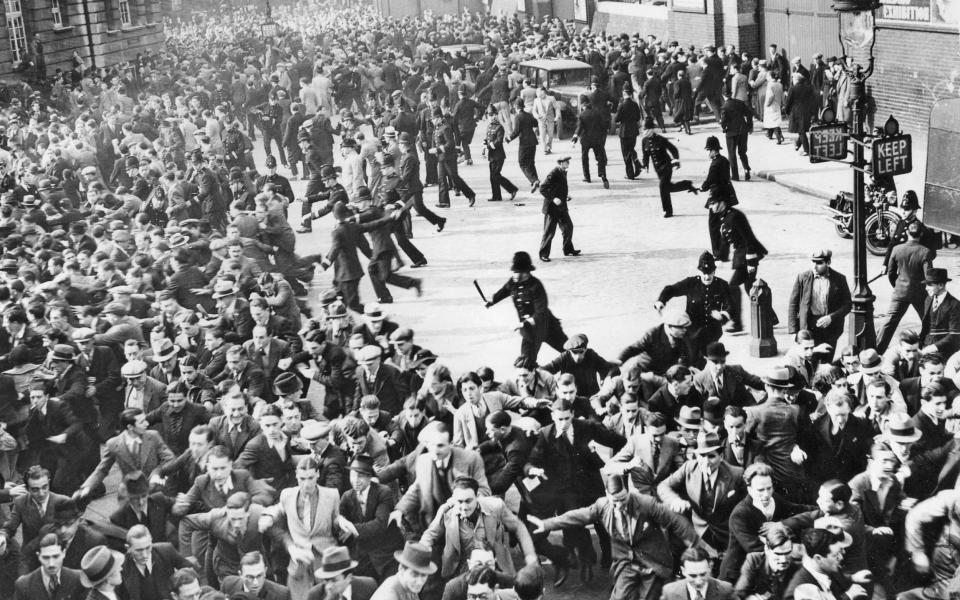

It is a riot of color and sound. In fact, it’s a plain old riot: the 87-year-old Battle of Cable Street is brought to life for a new musical, now showing at the Southwark Playhouse. As the boots of authoritarianism marched across Europe, Britain had its own demagogue, Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, whose members regularly beat Jews in the streets. On October 4, 1936, Mosley wanted to parade straight through the Jewish East End as a brutal provocation. The people of East London – not only Jews, but also Irish dockers, communists and trade unionists – united to stop him.

As many as 300,000 (estimates vary widely) appeared to block the path of as many as 5,000 Blackshirts in military formation. They eventually engaged in hand-to-hand combat with mounted police, who eventually persuaded Mosley to divert the march for fear of further bloodshed.

The battle provided the backdrop for Arnold Wesker’s 1958 state-of-the-nation play Chicken Soup with Barley, and was featured in a 2019 episode of EastEnders, which featured the death of the show’s first Jewish character, Dr. Legg, was shown. But something has caught the spirit of the times: also this week, Tracy-Ann Oberman’s Cable Street set The Merchant of Venice 1936 was transferred to the West End.

“It seemed like a really important story to me about the times we live in,” says composer and lyricist Tim Gilvin, who is descended from Irish Catholics who lived near Cable Street. “This is about people’s fear that others are being abused for political gain.” His ‘melting-pot score’ covers genres ranging from rap and folk punk to Britpop and music hall. There are also Spanish melodies – a nod to the influence of the anti-fascists of the Spanish Civil War on the counter-protesters, who used ‘No pasarán’ or ‘They will not pass’ as their slogan.

“I think history repeats itself,” says director Adam Lenson. “Cable Street is being interrogated as we figure out how to make this current moment a reality.” Gilvin performed the first song, Only Words, at Lenson’s Signal concert series in 2018. That evening, he was told by a mutual friend that playwright Alex Kanefsky was talking about writing a Cable Street musical. They joined forces and presented another song at a pandemic-era Signal concert, which was broadcast online and was seen by producer Dylan Schlosberg, who commissioned the show.

Lenson is ready to take on anyone who is skeptical about musical theater tackling such a weighty history. “It’s been the project of my life to convince people that we need to stop underestimating musicals,” he says. “Musical theater can be anything and everything. The fact that this is so rarely allowed is normally a commercial constraint in terms of what people think it sells.”

Danny Colligan (Dirty Dancing), Sha Dessi (Les Misérables) and recent graduate Joshua Ginsberg play the three young protagonists: Ron, a northerner hired by the fascists, Mairaid, an Irish poet who is told by her mother that “a dream never did the dishes,” and Sammy, a former boxer who struggles to get work due to anti-Semitism. Only after he was cast did Ginsberg discover that his great-grandfather Isidor Baum fought on Cable Street and returned home bleeding profusely.

The battle is also a celebrated moment in my family’s history. My “Aunt Hannah” – my father’s cousin, Hannah Grant – was a passionate 15-year-old who lived at 183 Cable Street. I first interviewed her for a primary school project in the mid-1990s, and then again for the 70th and 80th birthday celebrations, before her death in 2017, at the age of 96.

Outraged by the BUF’s “bloody cheek”, she spread from door to door and went with her brothers that day, ignoring the orders of their parents, Jewish leaders of the Council of Deputies and the Jewish Chronicle. While men tore up paving stones and women emptied chamber pots from upstairs windows, Hannah took to the streets armed with marbles in her pocket: “When the police horses passed by, you waited for them to flood.”

In 2006, I returned to Cable Street with Hannah and two other veterans, Aubrey Morris and Ubby Cowan. I vividly remember Ubby telling me how he was pushed through the window of a department store by police with ‘bats the size of broomsticks’ at Gardiner’s Corner, the main focal point. His brand new sports jacket was shredded. His grandson, Yoav Segal, is the musical’s set designer.

This is a proud chapter in British Jewish history. It is also an illustrious event for the left. Jeremy Corbyn is much parodied for regularly harkening back to 1936. When questioned in 2015 about his alleged links to a Holocaust denier, he replied: “My mother stood in Cable Street next to the Jewish people and the Irish people. We all have a duty to oppose any form of racism wherever it emerges.”

Cable Street’s legacy includes the Public Order Act 1936, which bans the wearing of political uniforms by the public and allows police to ban or change the routes of marches. But Gilvin – who left Mosley out of the show to avoid giving him “too much oxygen” – is aware of the danger of mythologizing. “Our musical doesn’t end with the Battle of Cable Street, because a week later the East End experienced its worst night of anti-Semitic violence in decades [the “Pogrom of Mile End”], and membership of the BUF increased. It was a symbolic victory.”

Lenson, whose great-grandparents owned a hat shop in Cable Street, was an outspoken critic of Jewish extermination in art. He was at the forefront of ‘Falsettogate’ – the 2019 row over a London staging of the musical Falsettos, which is about a Jewish family but had no Jews in the cast or crew. “Jewface” began to enter the lexicon.

He also took on the Royal Court Theater for its decision – despite warnings of the offense – to give a greedy billionaire the unmistakably Jewish name Hershel Fink in the 2021 play Rare Earth Mettle. “What I’m so happy about is that there are both Jews playing Jews and non-Jews playing Jews,” he says. “Making the show feels a bit like karmic payback for some pretty painful years of activism in an industry that I unfortunately still find a bit anti-Semitic.”

He points out the misconception “that Jews control or are even very present in the British theater scene” – he has heard racist comments said with abandon. “I once told someone I was doing a job in the opera and the money was a little better than in musical theater, and they said, ‘Good Jewish boy, follow the money.’” He says he “definitely did his job.” lost by speaking out. After a while, people hear the tone of complaint louder than the sound of injustice.”

In November last year, 100,000 people marched through central London to protest the post-October 7 revival of anti-Semitism, in what was described as the largest demonstration of its kind since Cable Street. The trade unionists, communists and Corbynites were conspicuously absent.

I ask Lenson if he sees such diverse groups coming together again. “I hope so,” he says. “One of the reasons Cable Street is popular is because it has a small dose of idealism. So yes, I am an idealist and I would like to believe that when the real darkness comes, people will know what is right.”

‘Cable Street’ is at The Large, Southwark Playhouse Borough, London SE1 until March 16