When Gregory Doran asked Ian McKellen to play Falstaff for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2014 production of Henry IV, he declined. “I told Greg the role was too hard,” says McKellen, “and I wasn’t sure if I would feel fat enough inside if I put on a fat suit.”

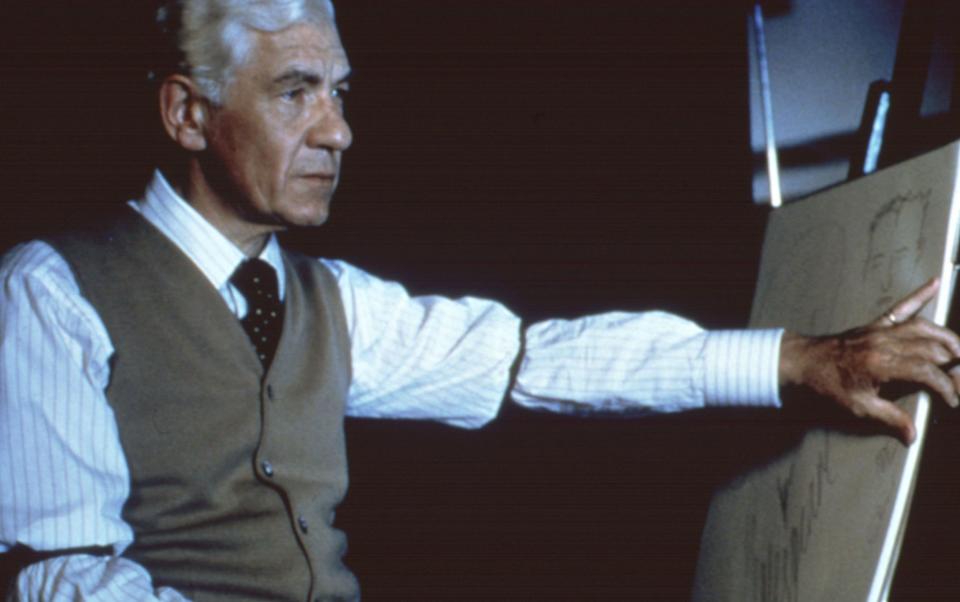

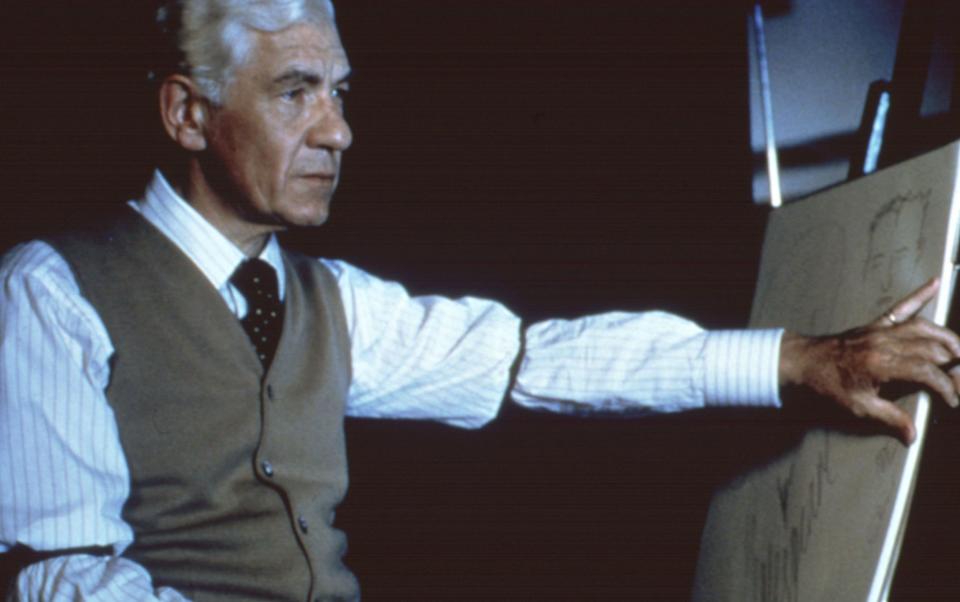

Ten years later he was asked to take on the role again, this time by director Robert Icke, for Player Kings, his new adaptation combining the two Henry IV plays. Would he refuse a second time? Little chance. During a break during rehearsals in south London, I ask whether Falstaff is as slippery to nail as McKellen feared.

“Worse,” he gasps. “He looks like something out of The Sopranos: a petty criminal, a Lord of Misrule, a man you wouldn’t let near your children. He’s much harder to play than Lear or Macbeth.’

Difficult? John Falstaff, the incarnation of jolly old England, who spends most of his time tending the bar at The Boar’s Head with the errant Prince Hal? “In a Shakespearean monologue, the character never lies. But Falstaff always does that,” says McKellen. “In Lear and Macbeth, the plays carry the character. But at Falstaff you are the engine. He also speaks in prose, rather than blank verse, which is why I have so much trouble learning the lines.”

The late American critic Harold Bloom argued that Falstaff was “the greatest personality in all of Shakespeare”; McKellen believes that “Bloom was one of the few people who could understand him”.

McKellen turns 85 in May. He could be at home in his mansion on the Thames, basking in the glory of a career filled with legendary plays – Macbeth in 1976; Salieri in 1980s Amadeus; Richard III in 1990. Instead, he worries about Falstaff. Why did he do this to himself?

“Isn’t it ridiculous? After I did Lear again in Chichester I said no more Shakespeare. I’m done!” That was in 2017. Four years later, he accepted an invitation from director Sean Mathias (who had been McKellen’s partner throughout the 1980s) to play a strikingly elderly Hamlet at the Theater Royal Windsor – a production for which Mathias has now made a new version. the cinema. “He seemed to think I could do it. So I keep going. Shakespeare is what I have been doing for so long, it confirms that I am still alive.”

McKellen is in remarkable shape, but it’s been a long day and he’s tired. Does he seek solace in these great Shakespearean parts – Lear, Hamlet, Falstaff – each in their own way confronting mortality?

“Falstaff actually sends his water to the doctor,” he says, laughing. “There aren’t many plays where a character says, ‘Has the doctor looked at my monster yet?’ He knows that he is old, that he will die soon. The Henry plays are the great English plays: you get a picture of the country from top to bottom, from monarch to prostitute, from Westminster to Cheapside. But they are also about death. The plays are immortal and I am not. So I hitch a ride.”

McKellen doesn’t work to keep busy, but because he finds value in it. “If I got stuck in a light comedy on the box, I’d think, ‘God, what’s the point?’ But in the theater, life happens now. That’s Falstaff’s first word: “Now!” There is no life reported, it is life there.”

He despairs at Westminster’s cavalier attitude towards this art form. “Theater is in the fabric of what makes us British. So why isn’t the government saying this should be preserved and encouraged?”

McKellen was born in Burnley in 1939 and graduated from Cambridge in 1961; while there, he played Justice Shallow in a production of Henry IV, with fellow student Derek Jacobi as Prince Hal. In 1965 he joined Laurence Olivier’s National Theater Company at the Old Vic.

“When I started as a young actor, you were a civil servant, paid by the government or local government to serve the nation. It was an honorable job. You had to join the union [Equity] and that was only possible after you had been in the regional theater for 44 weeks. It was a forced internship outside London.”

He saw all that change when Margaret Thatcher waged war on the unions. “In one fell swoop, she destroyed a system designed to protect actors’ livelihoods and began the decline of regional theater,” he says. “She didn’t think, she didn’t know and maybe she didn’t care. If I lived in any other city in Britain now, I would resent the fact that the best of British theater tends to stay where it is. The National Theater is no longer touring. The National Theater!”

McKellen, an instinctive activist who protested Section 28 in 1988 and co-founded Stonewall a year later, toured his own one-man show in 2019 to raise money for 80 regional theaters. “These are the kinds of things that bother me and that I’m trying to do something about.”

His big screen career owes a lot to theatre: his film of Richard III was nominated for five Baftas in 1997, putting him firmly on Hollywood’s radar. A starring role in the 1998 James Whale biopic Gods and Monsters earned him an Oscar nod, followed by a second, three years later, for his unforgettable performance as Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings.

Neither nomination led to an award – but McKellen doesn’t care. “An Oscar is an award, not an achievement,” he says. “You won’t find an actor who really believes in it. Anyway, if you are nominated you are expected to do a lot of publicity to encourage Academy members – you are essentially campaigning to get their votes! I don’t think not winning it is a failure.”

Brendan Fraser, his co-star in Gods and Monsters, won the Oscar for Best Actor last year for The Whale, in which he donned 300 pounds (130 kg) of prosthetic fat to play a morbidly obese teacher. Presumably those who accused the film of fatphobia will also take issue with the sight of slender McKellen donning a fat suit in Player Kings.

“Would it really be better if I put the weight on and then took it off again after production?” he asks. “Growing up, I don’t remember ever seeing an obese child – we were all on rations or eating food from the garden. Likewise, Falstaff’s obesity is constantly mocked, in a way that makes you think there weren’t that many fat people around in the late 16th century.

“Fatness is not always about lifestyle. Overall, though, it’s mostly true – and that’s all I want to say about being fat.”

The turn of the millennium ushered in one of the most surprising phases of McKellen’s career, as this August Shakespeare became a star in big-budget blockbusters including the X-Men and The Lord of the Rings franchises. “I enjoyed working in Hollywood – it felt thrilling, exhilarating and brutal to be accepted into an alien world,” he says now. “But to be honest, I was never that interested in it.”

He is also not exactly enthusiastic about the place itself. “It feels like apartheid. Go to Beverly Hills and the expensive real estate is owned by white people. The only non-white people are waiting at the bus stops to go back to what you might call the ghetto. You don’t have to look to Hollywood for social progress.”

Has he experienced any homophobia in the United States? “Never. When I worked there, the person I saw the most was David Hockney. And Gore Vidal. You didn’t feel like you were alone with those giants around.”

McKellen, who lives alone, has never hidden his sexuality from his friends. Before Mathias, he had an important relationship with Brian Taylor, a history teacher, in the 1960s. Shortly after we meet, it is reported that he has split from Oscar Conlon-Morrey, a 30-year-old actor with whom he appeared in the 2022 pantomime, Mother Goose – but McKellen declines a subsequent request to comment on the matter off.

Still, making his homosexuality public had an empowering impact: “I freed myself internally and emotionally,” he says. He recalls a 1992 National Theater production of Uncle Vanya, in which “in the Act Three scene, when Vanya collapsed, I began to sob effortlessly. That had never happened to me before and I could only think that it was because there was nothing in me that I wanted to hide from anyone anymore. In that sense, my acting got better. Of course everything gets better: your relationships; your self-esteem; your place in society.

“I love seeing the confidence of young people who never got out because they were never in,” he adds. “They don’t live in a world where the closet is a required way of life.”

He has no doubt that his family “would have absolutely accepted who I was” if they had known. His father, a civil engineer, died in 1964, ten years after 12-year-old McKellen lost his mother to breast cancer, a “devastating” blow from which he believes he never fully recovered.

“Then I thought it was doable. Looking back, I don’t think so. At 12, there isn’t much point in losing the person you love most and who seems to love you back. They are irreplaceable. All my life, every time I fall in love with someone and want to devote myself to him or her, I always wonder: will they leave me one day?”

It’s a rare admission from a man who always seemed safest in his own skin. But when he gets up to go home, McKellen is nothing if not optimistic. “When the body gives out and your back hurts, well, there you go. You have to put up with that. If your mind is young, you can do anything.”

Player Kings is at the New Wimbledon Theatre, London SW19 (playerkingstheplay.co.uk), March 1-9, then on tour; Hamlet will be in cinemas for one evening only on Tuesday