Everyone is so preoccupied with emotions over Gareth Southgate’s departure that the departure this week of another leader of a similarly troubled British institution has gone relatively unnoticed.

On Monday, Burberry’s board announced that Jonathan Akeroyd, the CEO who had been at the helm for just two years, would be leaving the position.

The parallels are almost too painful to contemplate. But we must contemplate them. England’s elite football team has brilliant components, but a problem with goals: it can’t score enough.

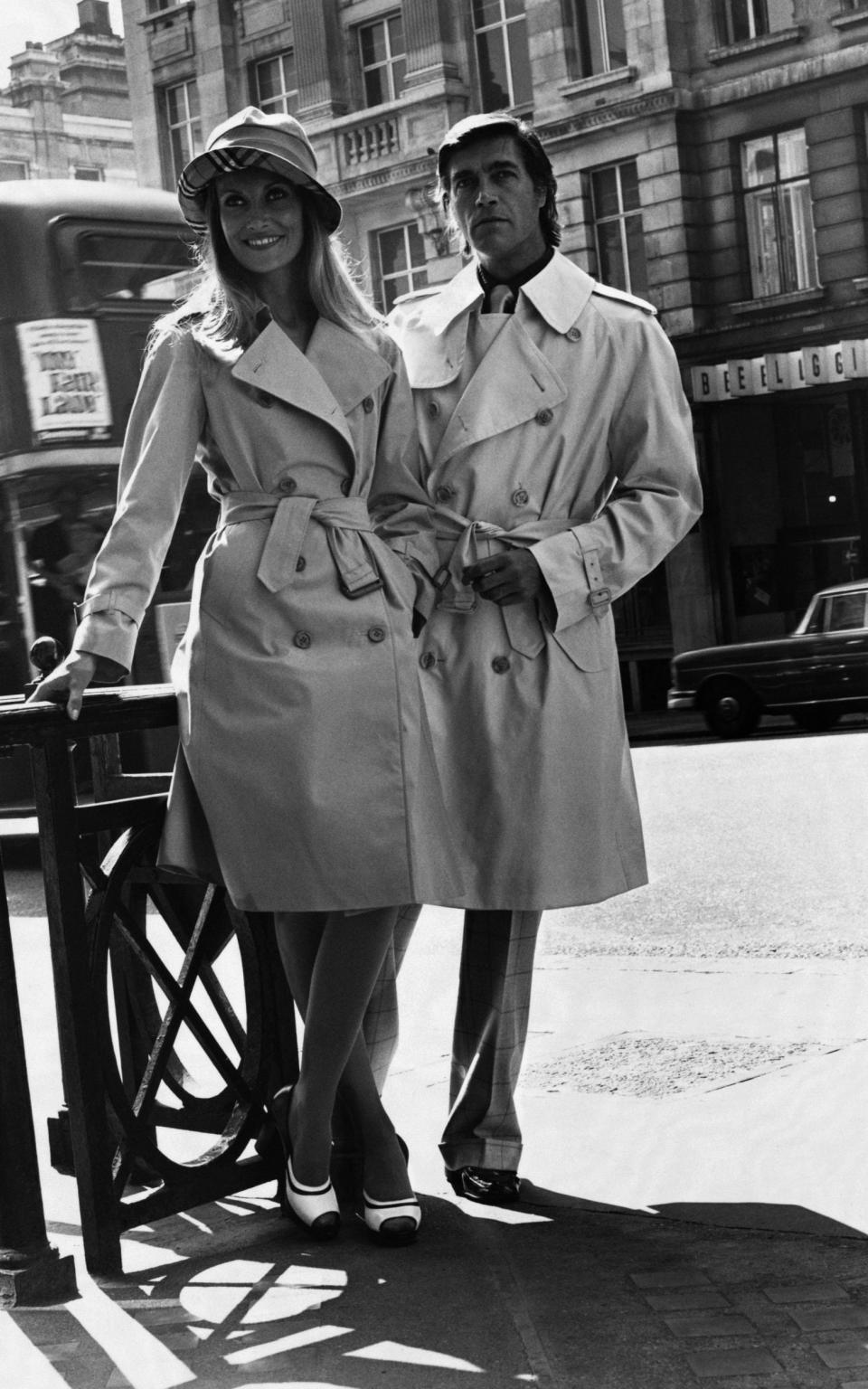

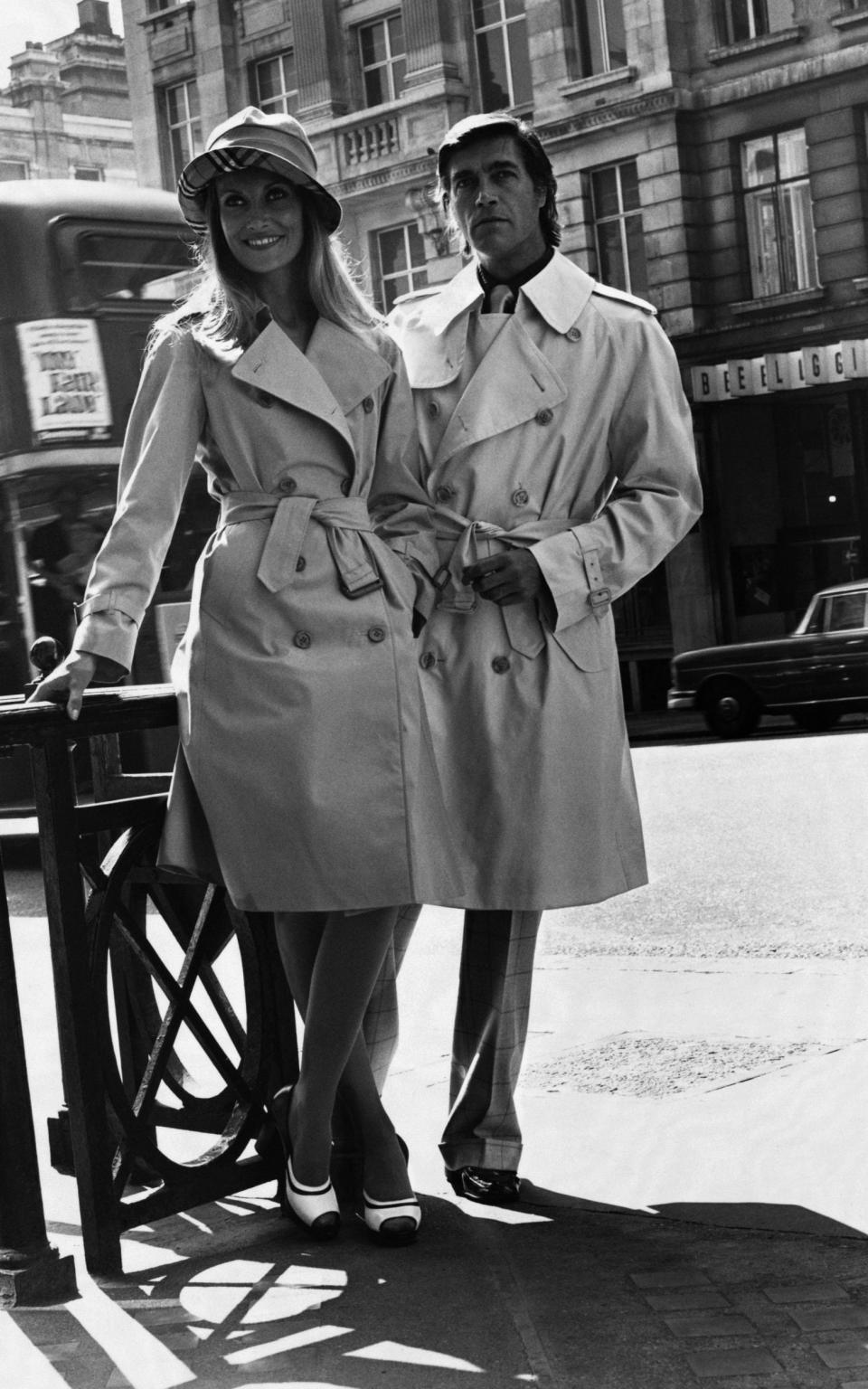

Burberry, too, is full of promise – unparalleled history, a royal warrant, a reputation, still, for the ultimate trench coat. But the problem is sales. There aren’t enough of those either.

In the first quarter of this year, they were down 21 percent. That was after a bleak period in 2020, 2021, 2022, etc. Both brands – the Lions and the Burberry Knights – may seem like the right choice, but when it comes down to it, they both, like their fans, suffer from a chronic lack of self-confidence.

Take Burberry’s commendably swift announcement that Akeroyd would be replaced by Joshua Schulman, who recently led Michael Kors and Coach.

Normally, the swift appointment of a successor is enough to calm a nervous stock market. But Burberry shares fell even further – by more than 15 percent. Because, whoah… Burberry is supposed to be top-notch. While Coach is… well, coach.

And Kors was all about moving mountains of £300 bags. Schulman did well with both. But this is the Championship, not the Premier League.

That’s worrying. Like M&S and Colin the Caterpillar, Burberry is one of those British icons that sets the mood music for the economy. Right now, the soundtrack at Burberry is Götterdämmerung.

Granted, its current valuation of $4.07 billion sounds impressive considering all the blows it’s taken in recent years. But Italy has Prada ($17.7 billion), Armani (£5 billion), Moncler ($17 billion), Dolce & Gabbana ($6 billion) and Max Mara – all still proudly owned by Italians.

France has Chanel ($25.2 billion), Louis Vuitton ($36.4 billion), Hermes ($22.1 billion)… You get the idea. In a global context, Burberry is a small fry.

But it’s our little fish, and we need it to thrive because it’s hugely important to the British fashion industry. The rise of Burberry in the 90s and 2000s changed the perception of Britain as a style powerhouse.

From musty tourist trinkets to flagship fashion on Bond Street and Madison Avenue and Mario Testino campaigns starring Kate Moss, Stella Tennant, Eddie Redmayne and Rachel Weisz, it changed the way international players thought about Britain as a place where luxury giants could thrive.

Under the creative leadership of Christopher Bailey and CEO Angela Ahrendts, Burberry rediscovered its British heritage and became a global brand.

Yes, there were some setbacks: overexposure in the early 2000s saw the famous Burberry check become synonymous with a raunchy celebrity culture.

But Bailey kept his cool, stepped away from the check and focused instead on creating the world’s best trench coats. “Doing a Burberry” became a byword for rejuvenating dusty old brands and making them culturally relevant and hugely profitable.

Its success was partly a reason for the Gucci Group, then co-owned by Tom Ford, to establish its headquarters in London rather than Paris or New York.

It meant that London Fashion Week, always the poor relation of Milan and Paris, suddenly had a hot property advertising in the world’s major markets. As a result, it attracted big editors and celebrities to its shows here. Other, much smaller designers basked in the reflected glow, attracting attention they had never had before.

Burberry could have done better by bringing more production in-house. But at least the numbers we saw up and down showed that we could think big and ambitious at the luxury level.

But after Christopher Bailey – and his unyielding vision – stepped down in 2018, Burberry, like our national football team, appeared to lose faith in its value as a truly elite player.

Bailey’s successor, the Italian Riccardo Tisci, had neither the temperament nor a clear understanding of what the brand should stand for (mainly functional but stylish outerwear).

His successor, Yorkshire-born Daniel Lee, who was appointed creative director in 2022, has yet to convince fans.

There is a dispiriting pattern here. Despite its exquisite craftsmanship and the support of the Princess of Wales and Anna Wintour, Alexander McQueen has yet to achieve the commercial potential that its owner, Kering (formerly the Gucci Group), hoped for when it acquired a majority stake in 2000.

Mulberry, another British success, also ran into trouble in 2012 when CEO Bruno Guillon decided the brand needed to move from a British idea of luxury (quirky, practical bags costing up to £1,000) to a French one (more expensive bags costing £2,000).

Perhaps part of the problem is that the British sense of luxury is out of sync with the rest of the world – more restrained, more pragmatic, rooted in our love of outdoor sports and military tailoring. In short, less flashy.

The brazen logos that even a brand like Prada now feels obliged to splash across its accessories and clothes are still seen as immodest by some Brits. And as for the impossibly soft vicuña yarns and clotted cream leathers at Loro Piana and Brunello Cuccinelli: please give us some rain- and windproof Harris tweeds and scratch-resistant duffel bags instead.

Another problem is that if we do buy something extremely expensive and luxurious, we prefer to choose Chanel or Dior rather than a less luxurious brand from England.

All this is not to say that we don’t have great designers who use top quality fabrics, produce in small quantities and quietly provide customization and haute couture services to high-paying clients.

Anya Hindmarch, Erdem, Emilia Wickstead, Roksanda, Anna Valentine, Métier London and Suzannah London (who designed the Duchess of Edinburgh’s beautifully embroidered coronation dress) all do so.

And then there are the lesser-known designers, like Claire Mischevani and Fiona Clare, who dress the royal family.

But with the exception of Manolo Blahnik, who is a genius, most of these companies generate between £3-20m a year, some much less. Unless they launch perfume, sunglasses and make-up – all incredibly difficult to do without the infrastructure of an umbrella conglomerate like Kering or LVMH – that is unlikely to change.

Making Burberry more mid-market, as some industry experts believe Schulman is now doing, could be a logical step to improve sales.

But it also means that the British dream of becoming a breeding ground for luxury giants that can take on the French or Italians has been put on hold indefinitely.