Strange as it may sound, early germ theorists could tell us a lot about current attitudes toward climate change.

While researching a new book on the history of emerging infections, I discovered many similarities between the early debates about the existence of microbes and the current debates about the existence of global warming.

Both controversies reveal the struggles of perceiving an invisible threat. Both reveal the influence of economic interests that profit from the status quo. But more importantly, both reveal how people with different beliefs and interests can still agree on important policies and practices to address a global problem.

What you can’t see can hurt you

Seeing is believing, and until the mid-19th century it was very difficult to see the tiny organisms responsible for our so-called ‘febrile’ illnesses.

Although the circumstantial evidence was compelling, many people remained skeptical of “animalcules”—as microorganisms were once called—until the microscope was sufficiently developed. Even then, acceptance was gradual. The once-dominant ideas about disease-causing gases, called miasmas, persisted for decades before most people recognized that the fevers had a living cause.

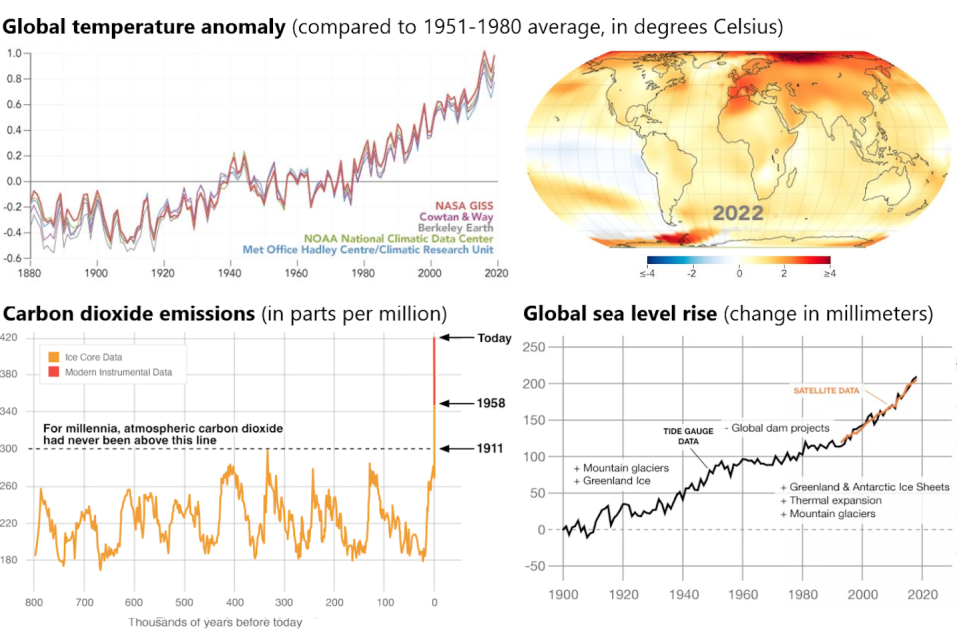

Climate change presents similar challenges in terms of visibility. While everyone can see and feel the weather, it is often difficult to observe the larger patterns and longer trends without the help of technical charts.

Even if people recognize the bigger picture, the case for human responsibility is complicated by the fact that the carbon emissions from our engines, like the bacterial infections in our bodies, are invisible to the naked eye. It is difficult to find human solutions when the evidence of human causation is invisible.

Economics may outweigh evidence

In addition to these challenges, there are also economic interests that often hinder scientific recommendations.

In the case of the germ theory, initial recommendations to prevent the spread of infection included the reintroduction of quarantines at ports and border crossings, which hampered international trade flows.

In the case of climate theory, recommendations to slow global warming include reducing the consumption of carbon-based fuels, thereby reducing the flow of oil. These strategies can threaten both livelihoods and profits, so it is not surprising that unions are divided over green initiatives and energy executives who spread misinformation about climate science.

Beliefs and interests do not have to coincide

But people’s beliefs and interests do not have to match if everyone benefits from the recommendations.

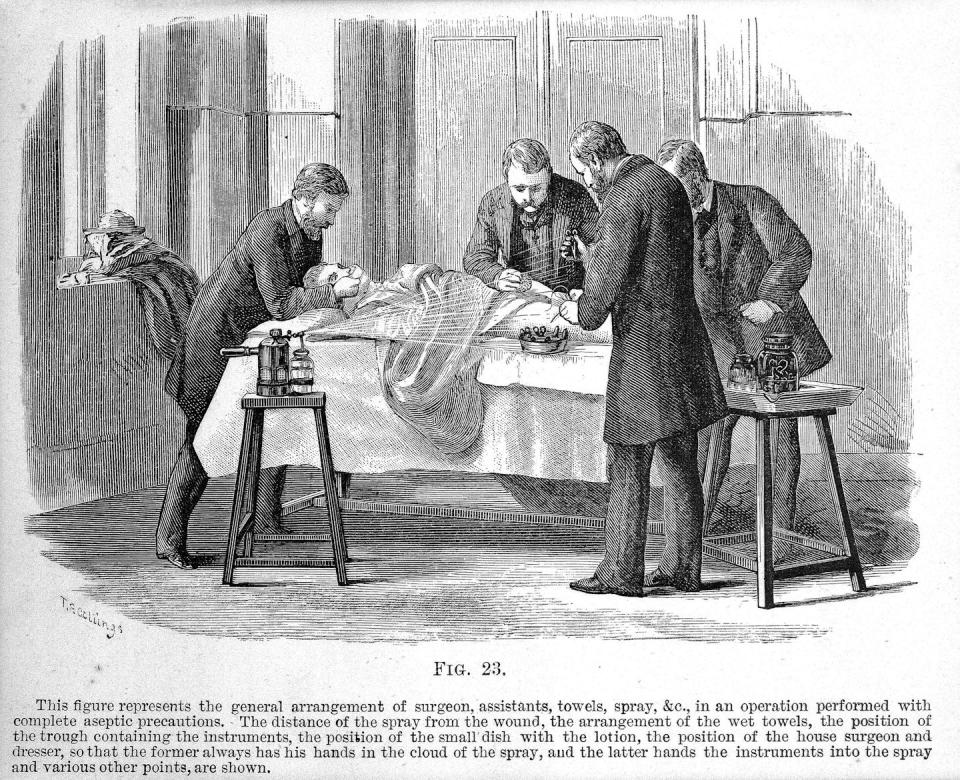

This was the case in the last decades of the 19th century, when surgeons who wanted to keep germs at bay nevertheless adopted the antiseptic techniques of Joseph Lister.

They did this primarily for the practical reason that their patients did better under the new methods. But when an explanation was needed, many of these die-hard skeptics claimed that Lister’s methods prevented the transmission of miasms rather than living organisms.

In response to these claims, Lister stated:

“If any one chooses to assume that the septic material is not of the nature of living organisms, but a so-called chemical ferment devoid of vitality… such an idea, however unfounded I believe it to be by any scientific evidence, will in a practical point of view be equivalent to a germ theory, as it will instil precisely the same methods of antiseptic administration.”

Lister was more concerned with saving lives than winning arguments. As long as surgeons adopted his methods, Lister cared little for their justifications. When it came to preventing infection, it was behaviors that mattered, not beliefs.

Behavioral change through complementary interests

The same goes for global warming: changing behavior is more important than changing beliefs.

An example is the large and growing environmental movement among evangelical Christians. Organizations such as Green Faith and the Creation Care Task Force cite Biblical scriptures to promote environmental stewardship as a sacred duty.

While many of these groups acknowledge human-induced climate change, some of their core beliefs contradict the evolutionary theories that my colleagues and I hold as scientists. But we don’t have to agree on fossils to move the world away from fossil fuels.

The same applies to priorities and economic interests.

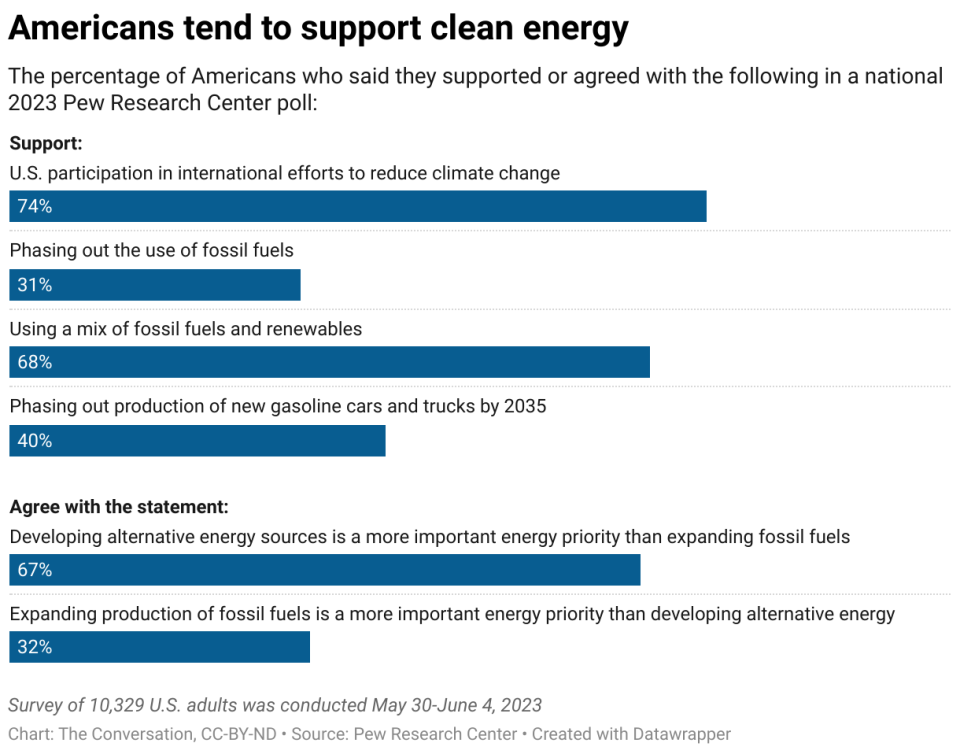

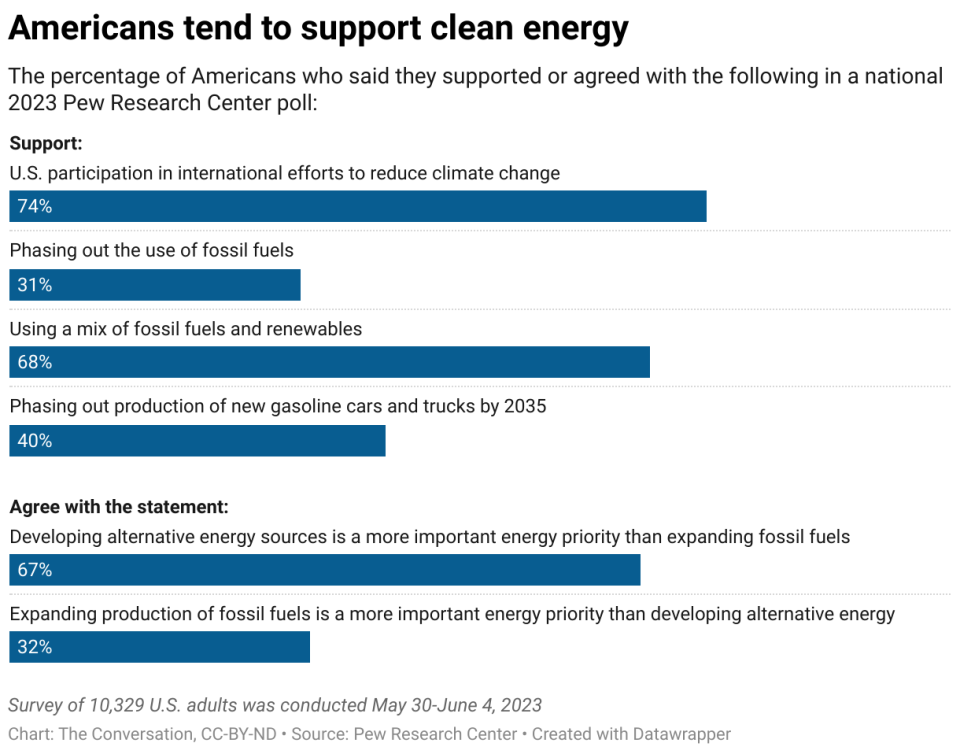

A recent Pew national survey found that a large majority of Americans support the development and use of renewable energy. This includes a slight majority of Republicans, although their motives often differ from those of Democrats.

Republicans are more likely to prioritize the economic benefits of renewable energy than Democrats, who cite global warming as their top concern.

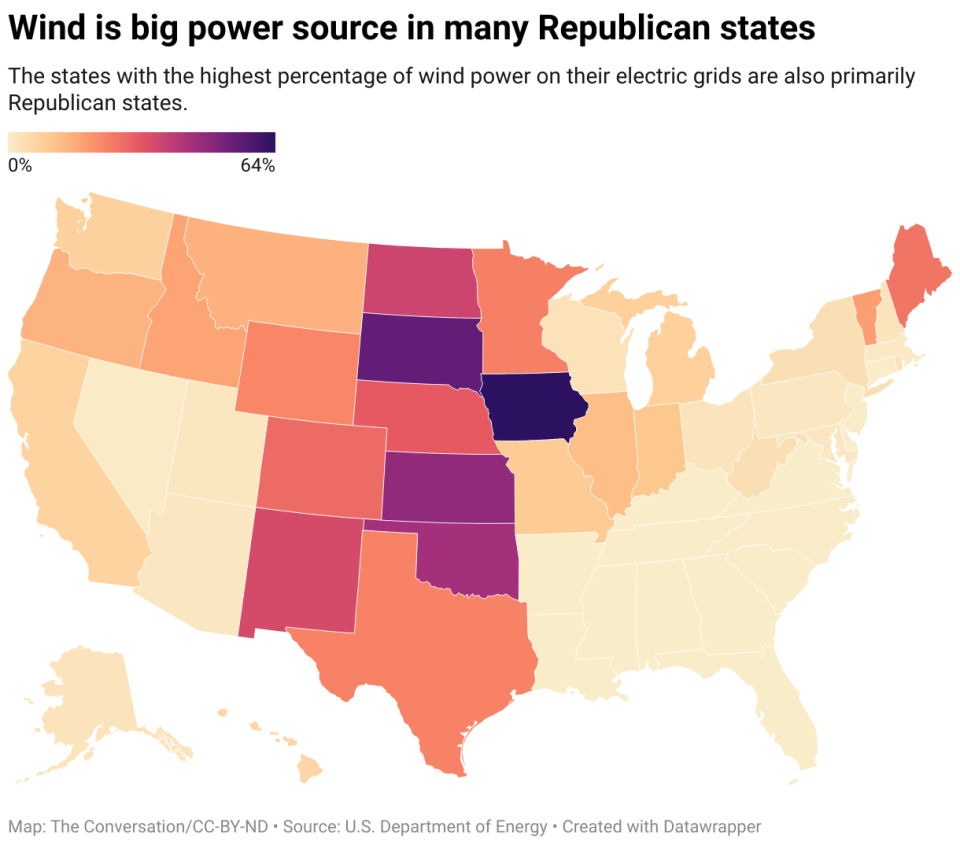

The economic benefits could explain why red states produce the majority of U.S. wind energy and why three of those states are among the top five solar producers in the country. Their adoption correlates with the geography of the wind and sun belts, where farmers see favorable returns for producing energy and a stable source of income to ride out the price swings of weather-sensitive crops. Livelihoods are a powerful motivator.

Finding common ground could change the world

None of these examples address climate change on all fronts. And there are differing views among Democrats and Republicans on how fast and how far the transition to renewable energy should go.

But we can learn one hopeful lesson from the 19th century: even though people didn’t agree on all the measures to prevent disease, they found enough common ground to achieve the greatest reduction in mortality in recorded history.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization that brings you facts and reliable analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Ron Barrett, Macalester College

Read more:

Ron Barrett is not an employee of, an advisor to, an owner of stock in, or a recipient of funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.