Caroline Herschel, the first English professional female astronomer, made contributions to astronomy that remain important to the field today. But even many astronomers may not recognize her name.

Most scientists are interested in the latest techniques, data and theories in their field, but often know very little about the history of their field. Astronomers, like me, are no exception.

It wasn’t until I was teaching an intro to astronomy class that I met Caroline. Thanks to a new exhibition of her papers at the Herschel Museum in Bath, England, others can now learn about her too. Her story reflects not only the priorities of astronomy, but also how credit is awarded in the field.

Her path to astronomy

Caroline Herschel, born in 1750, did not have an easy childhood. After a bout of typhoid fever left her scarred at a young age, her family assumed she would never marry and treated her like an unpaid servant. She was forced to perform household chores despite showing a keen interest in learning from an early age. She eventually escaped her family and followed her older brother William Herschel, whom she adored, to Bath.

Caroline was initially a somewhat reluctant astronomer. She only became interested in astronomy when William had already delved deeply into the subject. Although she spoke somewhat disparagingly about how she followed her brother into various interests including music and astronomy, Caroline eventually recognized her true interest in studying astronomical bodies.

At the time, astronomers were mainly interested in finding new objects and accurately mapping the sky. The use of telescopes to search for new comets and nebulae was also popular. William Herschel became famous after his discovery of Uranus in 1781, although he initially mistook the planet for a comet.

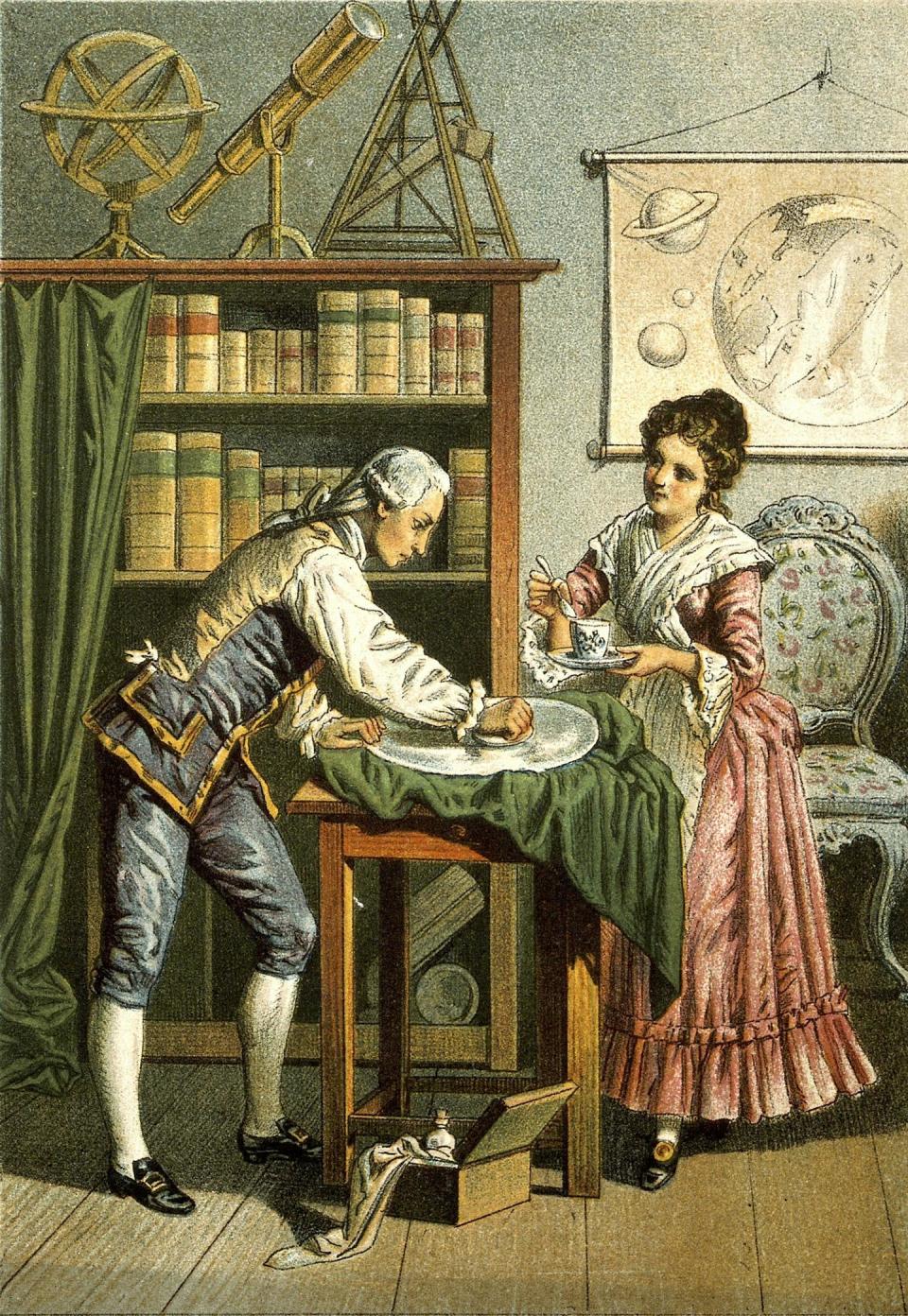

Early in her career, Caroline worked as William’s assistant. She focused mainly on astronomical instrumentation tasks, such as polishing telescope mirrors. She also helped copy catalogs and took careful notes on William’s observations. But then she started making her own observations.

Searching the air

In 1782, Caroline began recording the positions of new objects in her own logbook. Through this work she discovered several comets and nebulae. On August 1, 1782, she discovered a comet – meaning she was the first to see it with her own eyes in a telescope. This was the first comet discovery attributed to a woman. Over the next eleven years she discovered seven more comets.

At the time of the Herschels’ work, it was the actual observation of an object that deserved public recognition, so Caroline only received credit for the comets she herself saw through the telescope. For all her other work, such as recording and organizing all the data from William’s observations, she received less appreciation than William.

For example, when Caroline collected all of William’s observations into a catalogue, it was published under William’s name. Caroline is only mentioned in the newspaper as an ‘assistant’.

Nevertheless, in recognition of her discoveries and her work as William’s assistant, King George III of England awarded Caroline a salary, making her the first professional female astronomer.

Later in her life, Caroline reorganized the same catalog in a more efficient way, depending on how practicing astronomers interested in searching for comets actually observed the night sky. This updated catalog was later used as the basis for the New General Catalog, which astronomers still use today to organize the stars.

The Herschels also created the first – although not entirely correct – map of our galaxy, the Milky Way.

Who gets the credit in astronomy?

Recognition for scientific work within the astronomical community is very different now than it was in the time of the Herschels. In fact, most of the astronomers gaining recognition today are those whose work is much like Caroline’s: recording and organizing data from astronomical observations.

Astronomers rarely keep their eyes on a telescope’s eyepiece anymore, and many of the most important discoveries are made by telescopes in space. But astronomers still need to make sense of all the data from these telescopes. Catalogs such as Caroline’s are an important tool in this regard.

Most people today have never heard of Caroline Herschel. Although several astronomical objects – and even a satellite – are named after her, she does not have the same name recognition as other astronomers of her time. Part of the lack of recognition is probably because her brother took all the credit for her catalog. Today, astronomers would give them both credit.

Herschel is just one in a long line of female astronomers who were not given the credit they were entitled to and whose work was instead used to justify prizes for male scientists. These problems are not only limited to 18th century science, but persist in modern astronomy as well. Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who discovered the first radio pulsar, was no longer awarded a Nobel Prize in 1974 and the prize was instead awarded to her Ph.D. counselor.

Although astronomy has come a long way since the 18th century, astronomers still need to think carefully about how to fairly acknowledge the people who participate in scientific discoveries. Recognizing the contributions of astronomers like Caroline Herschel is a small step toward giving credit where credit is due.

This article has been updated to recognize other female astronomers who preceded Herschel.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Kris Pardo, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Read more:

Kris Pardo does not work for, consult with, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.