Claude Montana, the French fashion designer, who has probably died aged 74, defined the exaggerated silhouettes characteristic of power-dressing women in the 1980s, when he became known as the ‘King of Shoulder Pads’.

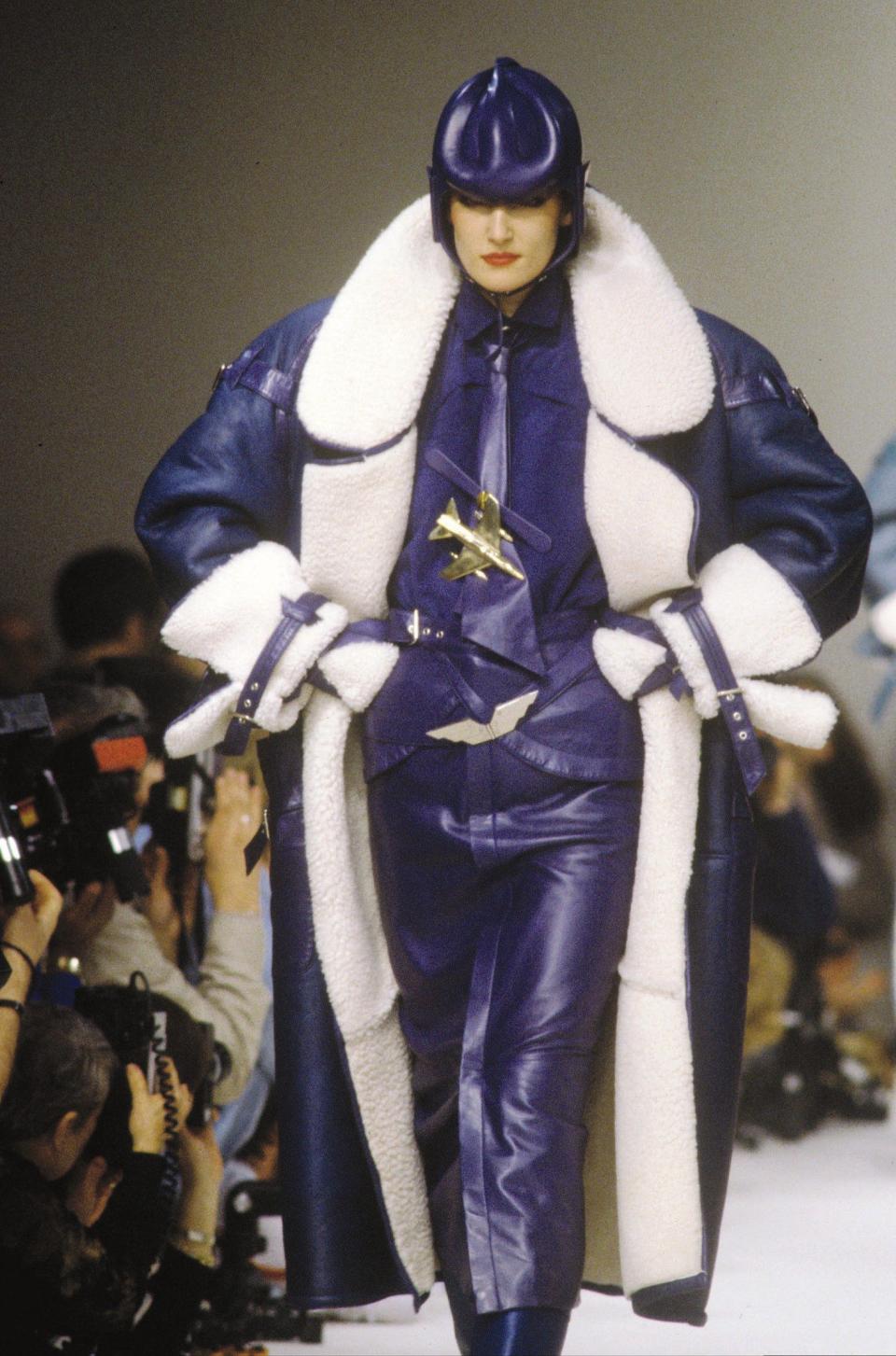

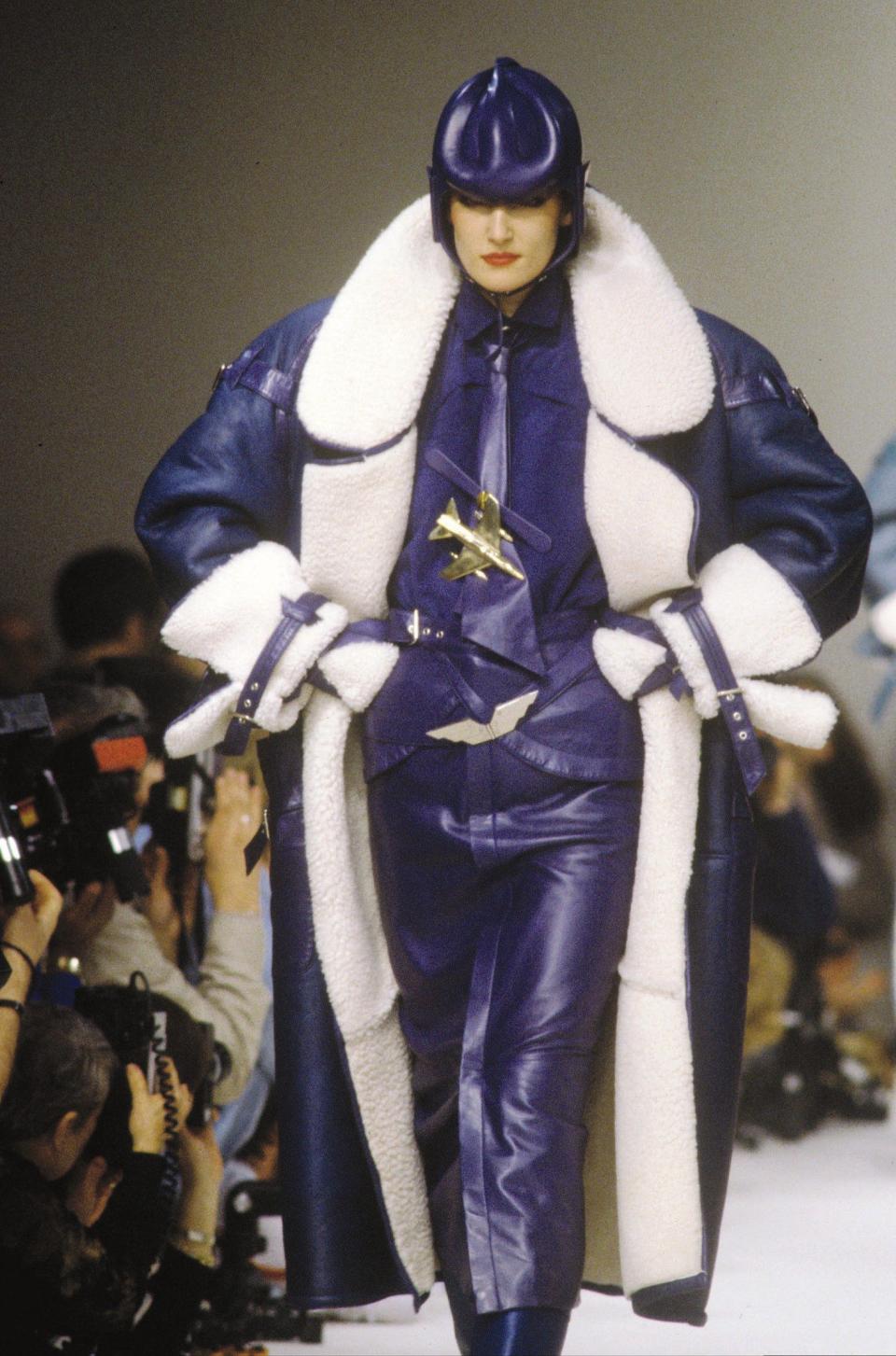

Initially, Montana’s aggressive silhouettes, heavily influenced by constructivism, shocked critics and buyers. His first collection from 1979, made almost entirely of leather, provoked a flood of abuse. Critics describe it as “flashy, messy and demeaning to women” and “whore fashion”. He was accused of being misogynistic and promoting a “neo-Nazi” aesthetic, although his aggressively sexual appearance with leather zippers and studs actually owed more to the gay subculture of which he was an active member than to any political movement .

Yet his razor-sharp tailoring, skill with leather and masterful use of color made Montana’s catwalk shows – with their haughty Amazonian models – the hottest ticket in town by the mid-1980s. What Montana did one season, others copied the next. Cher, Barbra Streisand, Diana Ross, Grace Jones, Elizabeth Taylor and Sally Field all wore Claude Montana – as did Don Johnson, Bruce Willis and Mickey Rourke.

In the late 1980s, his fashion empire included ready-to-wear for women and men; licensing products such as scarves, ties and glasses, and a best-selling perfume, Montana Pour Femme.

Then things started to go seriously wrong. In 1989 he turned down the job of chief designer at Christian Dior because he found the assignment too demanding. “I need space,” he told The Washington Post. “I don’t want to have all this money and go to an asylum.” The job went to Gianfranco Ferre. Later that year, the distressed house hired Lanvin Montana for its haute couture line. Montana won the Golden Thimble, couture’s highest award, two seasons in a row, but Lanvin lost too much money on couture and did not renew his contract.

Even by fashion industry standards, his dismissal was brutal. His employer called press hours after he showed his January collection in 1991 to announce that Montana was out. The highly sensitive designer was devastated.

Deeply wounded, he retreated to his clothing business and continued producing leather bomber jackets and zipper-encrusted dresses. But his designs seemed old-fashioned among the grunge, waif and romantic looks that monopolized the catwalks in the early 1990s. His futuristic all-white women’s collection for fall 1995 was critically acclaimed. Women’s Wear Daily concluded, “Nobody beats Montana for tailoring precision,” but it wasn’t enough to halt declining sales.

Meanwhile, his personal life was falling apart. In 1993, after being rejected by his longtime male companion, Montana shocked his friends by marrying his androgynous catwalk muse, Wallis Franken. In what was widely seen as a cynical move to prop up a faltering career, he staged the wedding in July, in the middle of Paris couture week, with the bride’s white satin cowboy jacket over the tunic and trousers contrasting with the buckskin suit of the groom.

Three years later, Madame Montana committed suicide by diving head first out of the kitchen window of their flat in the seventh arrondissement of Paris while her husband slept in his bedroom. Her jewelry was neatly arranged on the kitchen table. The model’s friends, and many people in the industry, indirectly blamed Montana. Not only had Wallis had to deal with her husband’s addiction to the gay club scene and his possessiveness towards her, he was also said to have ridiculed her as ‘old and ugly’.

The following year, Montana filed for bankruptcy.

According to several normally reliable sources, Claude Montana was born in Paris on June 29, 1949 to a German mother and a Catalan father, although some sources claim he was born two years earlier, in 1947. He fell into fashion by chance when his father tried to convince him to follow in the footsteps of his older brother, a scientist who conducts chemical research. “I had to leave the house,” he remembers.

He and a friend left for England, with no job prospects and no money. “We remembered a Mexican recipe for making bracelets from toilet paper, glue and rhinestones,” he recalls. They baked the papier-mâché jewelry in an oven at night and sold it on street stalls during the day. In 1971, his designs were featured in British Vogue, and he managed to get by for six months until he was asked to leave the country because he did not have a work permit.

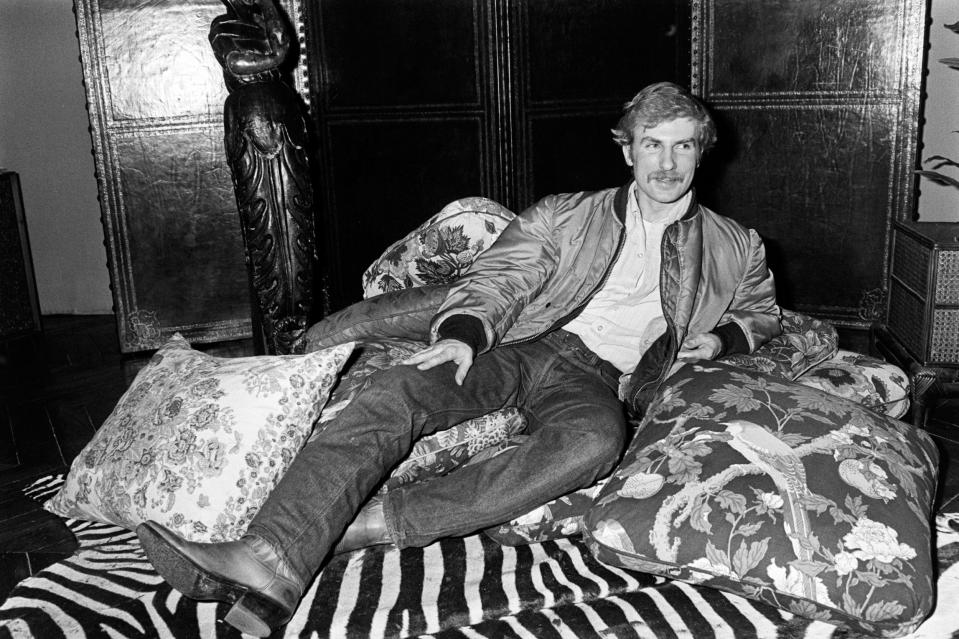

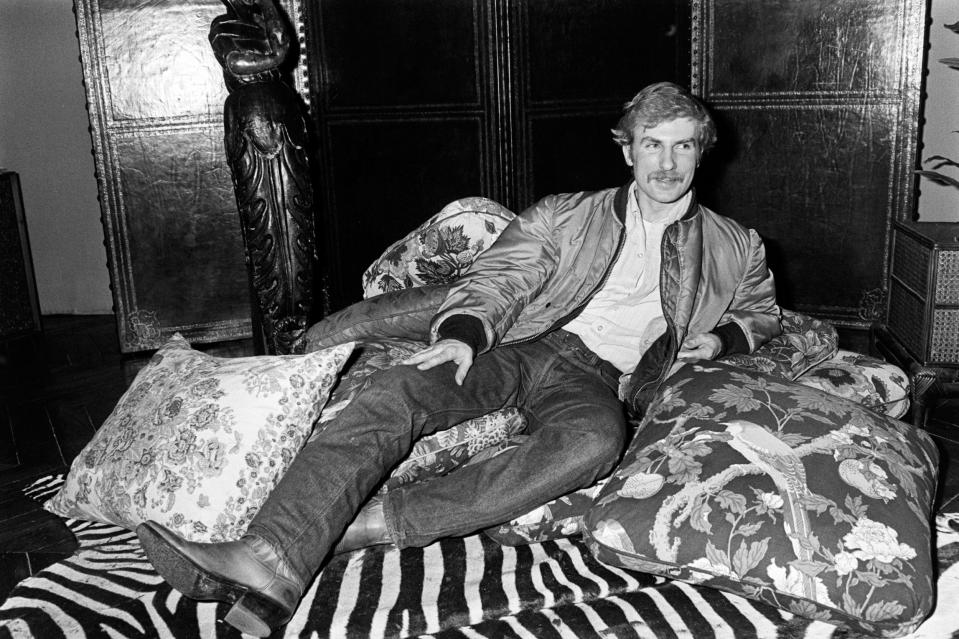

Montana returned to Paris, but failed to generate any interest in his jewelry designs. Instead, he tried to get odd jobs as an extra in the opera and films. He was openly gay, wore black leather, a Hitler mustache and dyed orange hair, and was rarely seen without a cigarette.

Eventually, a friend who made ballet costumes suggested he should go into fashion, and he found a job as a design assistant at a training company called MacDouglas, which took over when the designer left. He held his first fashion show in 1976. In 1978, he told Women’s Wear Daily, “Next season everything will have the biggest shoulders I can make.” So big, retailers later complained, that the clothes kept falling off the hangers. In 1979 he founded his own label.

From the beginning, Montana’s sexuality influenced his approach to design. An indefatigable clubber, he invariably appeared at Club Sept, a nightclub in Paris, at the head of a phalanx of leather-clad young men. So it was no surprise that his clothes for women spoke to the world he knew so well. He also had a penchant for uniforms, producing variations on the outfits worn by pilots, marines, factory workers and even members of the French Academy.

Over the years, Montana has honed his image as a tortured perfectionist. He was known to stay up all night before a show and throw tantrums over the slightest imperfection. He tended to avoid large social gatherings, even when he was the guest of honor. During a fashion week in Tokyo, when he was one of five designers whose work was on display, he turned down an invitation to a gala dinner and was instead seen at a nightclub where he stayed until six in the morning. He was not universally popular.

In 1998, a French investor group led by a former perfume house manager Nina Ricci acquired the Montana fashion business for about $821,000. Ironically, part of the agreement asked Montana to give up the rights to his name, something he had fought so vehemently for in the past. However, the designer would retain the right to design the home for another ten years.

Montana seemed happy with the arrangement and, freed from the pressures of running a business, he quickly recovered. In 1999, he unveiled Montana Blu, a line of affordable clothing for younger, hipper women, which was successful enough to spawn its own fragrance. Later, as fashion returned to harder, sculpted styles, Montana became an inspiration for a new generation of designers, including Alexander McQueen.

Claude Montana, born June 29, 1949, death announced February 23, 2024