The water cycle that cycles Earth’s most vital resource in an endless, life-giving loop is in trouble. Climate change has disrupted the delicate balance of that cycle, disrupting the way water circulates between the ground, the oceans and the atmosphere.

The events of 2023 show how extensive these disruptions have become. From extreme precipitation and flooding to drought and contaminated water supplies, nearly every part of the US has been impacted by climate change and changing water availability.

The water cycle controls every aspect of Earth’s climate system, meaning that as the climate changes, so too does almost every step of water movement on the planet. In some places, water availability is becoming increasingly scarce, while in others climate change is intensifying rainfall, flooding and other extreme weather events.

As the planet continues to warm, this cycle is expected to become increasingly stretched, distorted and broken.

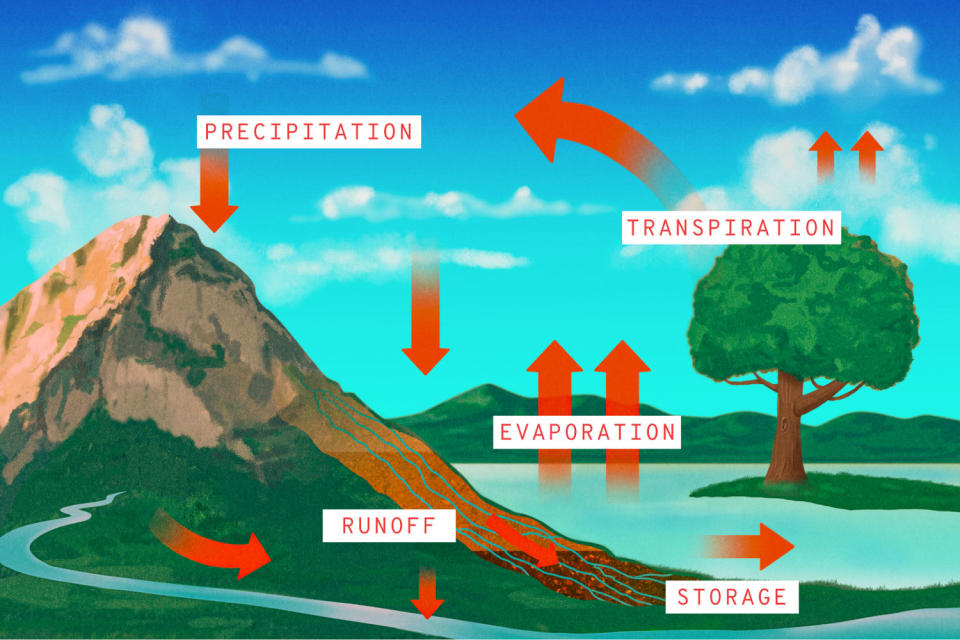

The water cycle – a staple of primary school science lessons — describes the constant movement of water in all its phases (solid, liquid and gas) on the ground, in the ground and up into the air. Powered by the sun and fueled by changes in temperature, the water cycle is the invisible link between Earth’s glaciers, snowpack, oceans, lakes, rivers, plants, trees, clouds and rain.

Liquid water flows over the land as runoff, with some of it seeping deep underground where it is stored as groundwater. Some of the water will flow into streams, rivers and other water bodies. And in some parts of the world, water is also stored in frozen form, as is the case with glaciers or snowdrifts. Water on the ground or in bodies of water turns back into water vapor through a process known as evaporation. Some of the water is also absorbed by plants before evaporating into the atmosphere, a process known as transpiration.

Water vapor eventually condenses into clouds. Precipitation falls as rain or snow, transporting water from the atmosphere back over land and starting the cycle again.

Human activities have a huge impact on the water cycle, as water is needed for drinking water, agriculture, industrial activities, electricity and more. Each of these uses affects the availability and supply of water, but climate change could put additional pressure on water movement between land, the oceans and the atmosphere.

Below, we walk through these crucial steps—precipitation, evaporation, transpiration, runoff, and storage—to illustrate how climate change is already changing our environment in ways that affect millions of people in the US.

In 2023, extreme precipitation, likely driven by climate change, hit almost every corner of the United States.

For every degree of warming in Fahrenheit, the atmosphere can hold about 3%-4% more moisture. Global temperatures in 2023 were 2.43 degrees higher than in pre-industrial times, meaning today’s storms could pack a stronger punch.

In Vermont, heavy rains in July caused flash flooding that nearly breached a dam in Montpelier and left streets flooded. In September, New York City saw a similar story play out, when some locations fell 12 inches of rain in 24 hours, flooding cars and city buses and disrupting train traffic.

The effects of storms are amplified in cities like New York, where storm drains and subway tunnels are in disrepair or were simply built for a milder climate.

Climate change is also changing the behavior of hurricanes, causing more extreme rainfall. Today, hurricanes are more likely to intensify rapidly, meaning they quickly increase wind speed as they feed on warming waters near the coast. And when these storms make landfall, climate change increases the likelihood that hurricanes will stall and dump incredible amounts of rain as they plod across the landscape.

As Hurricane Idalia approached the Florida coastline in late August, wind speeds increased by 60 mph in just 24 hours and the storm strengthened from a Category 1 to a Category 4 storm. The storm dropped more than 12 inches of rain on Holly Hill, South Carolina, the location hardest hit by rainfall.

Higher temperatures increase evaporation and transpiration in some areas, making drought more likely and putting pressure on plants, which was evident during a summer of extreme heat in 2023.

Due to climate change, droughts are becoming more frequent, more severe and lasting longer.

The ongoing drought caused water levels in the Mississippi River to drop to historic lows in 2023, allowing saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico to push upstream and contaminate urban drinking water supplies.

Meanwhile, drought in Hawaii increased the risk of wildfires by drying out vegetation and turning non-native grasses on Maui into a “ticking time bomb,” in the words of one researcher. A catastrophic wildfire, fueled by hurricane winds, ripped through the historic city of Lahaina in August 2023, killing 101 people.

Drought lingered in the Midwest and South from spring through fall, making it the costliest natural disaster of 2023 – worth $14.5 billion.

Climate change is changing the pattern and timing of runoff, especially in mountainous parts of the US, causing rivers to flow at extremely high and low water levels.

In Alaska, where temperatures have warmed about twice as fast as the global average, a glacial ice dam burst, sending a huge flood of water downstream, uprooting trees and flooding neighborhoods near Juneau.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the event would not have occurred without climate change and glacier retreat.

Warm spring and summer temperatures in the Pacific Northwest hastened the region’s melt, causing fall water supplies to fall short and straining the region’s capacity to generate hydropower.

Water supplies are declining in the western states, on the Great Plains and in some parts of the Midwest.

Years of overuse – partly due to rising temperatures and drought – are causing farmers to consume unsustainable amounts of stored groundwater and pushing some aquifers to the brink.

California was pummeled by extreme rainfall in 2023, when more than a dozen atmospheric river storms battered the state. The storms, likely amplified by climate change, eased a drought and blanketed the state with two to three times as much snow as normal.

But all that precipitation only made a dent in the state’s overall groundwater deficit after seasons of drought, and groundwater levels remained lower than they were after a previous four-year drought ended in 2016, according to the California Department of Water Resources.

Last year, several states agreed to cuts in use of the Colorado River, where reservoirs held only 43% of what they could store at year’s end, even after a year of heavy snowfall.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com