Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific developments and more.

For thousands of years, one color was more important than all others, and according to a fourth-century imperial edict, was worth more than its weight in gold.

Tyrian purple was a highly prized pigment that was developed in the Bronze Age and retained its status until the late Middle Ages. The ancient Greeks and then the Romans revered the royal color, produced from Mediterranean snails, for its resistance to the inevitable fading of vegetable dyes used at the time. But with the eventual fall of the Byzantine Empire, the recipe was lost.

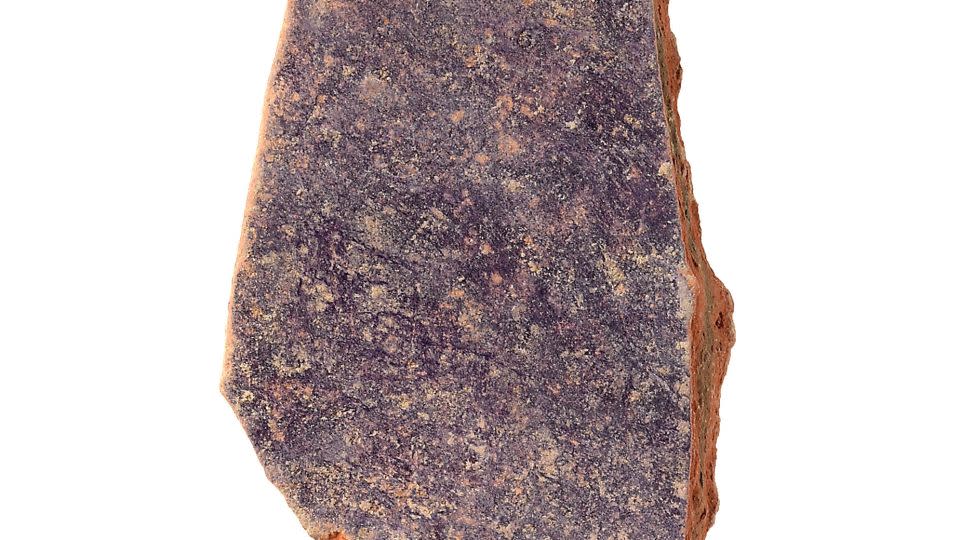

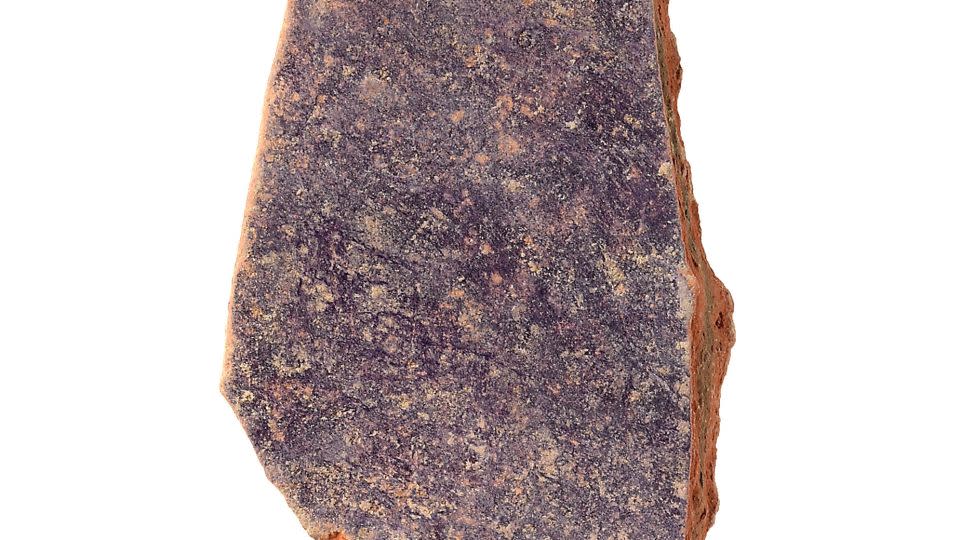

During an excavation of two early Mycenaean buildings discovered on the Greek island of Aegina, archaeologists unearthed several pottery fragments containing residues of 3,600-year-old Tyrian purple dye, according to a study published June 12 in the journal PLOS One.

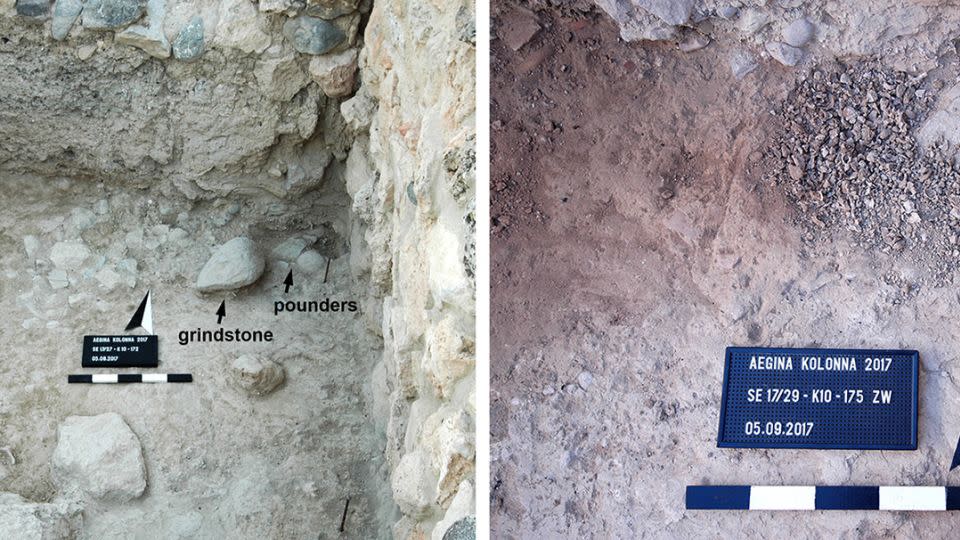

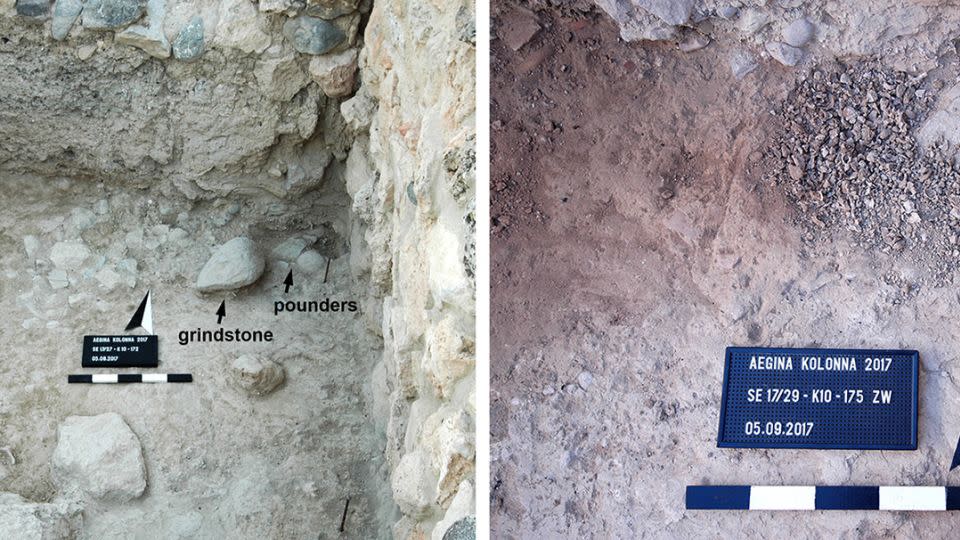

The pigment is so well preserved that it can still be used to dye textiles today, says lead study author Dr. Lydia Berger, a senior scholar in the department of classics at Paris’s Lodron University of Salzburg in Austria. The researchers also found broken shells of mollusks and several stone tools, probably used in the dyeing process.

The pigment, along with the other remains of an early functioning purple dye workshop discovered at the ancient site known as Kolonna, have shed some light on the mysteries that still surround the once highly sought-after color.

A difficult process for an elite color

The earliest record of Tyrian purple production dates back to the Middle Bronze Age (2000 BC to 1600 BC), the study authors wrote. Historians believe that people in the ancient city of Tyre, on the coast of what is now Lebanon, first created the dye, also called Mycenaean purple. The ancient Greeks called this region Phoenicia, or “land of purple,” according to the University of Michigan.

A combination of secrecy surrounding the process and a lack of early archaeological evidence from the Greek Bronze Age civilizations near the Aegean Sea likely led to the recipe being lost. It took hundreds of years of research plus modern experiments to get close to the supposed procedure.

“It was a trial and error process, and these people really knew the secret. Now we have lost all the secrets,” said Maria Melo, associate professor in the department of conservation and restoration at Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal, who was not involved in the discovery. “We most likely won’t be able to reproduce their process, but we can try to do something similar.”

Creating the historic hue required a huge number of sea snails found along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, as documented by ancient Roman authors. Dye artisans commonly searched for the species known today as the striped dye murex – the species favored by those on the island of Aegina, chemical analysis of the pigment found revealed – as well as the spiky dye murex and the red-mouthed rock clam, the study said.

Tyrian purple is often described in ancient Roman times as a deep reddish purple, but depending on the snail used and the amount of heat exposure, the hue can range from dark indigo to lilac or deep red, Melo said.

Once collected, the snails had to be kept alive until the makers of the purple dye were ready to crush them and remove the mollusk’s mucus glands. The snail remains would then be left to ooze for several days with regulated exposure to heat, as the color would change from yellow to green and then to purple and sometimes dark red, Berger said.

The process was accompanied by a fishy odor, an odor the researchers recognized when they came across the purple pigment remains during the recent excavation at Kolonna, she added.

According to one estimate, it could take as many as 12,000 snails to get 1 gram of dye. But modern experiments have shown that fewer snails can yield the same amount of dye, depending on how light or dark you want the pigment to be, says Rena Veropoulidou, an archaeologist with the Greek Ministry of Culture in Greece, who was not involved in the find. new study. For example, in a 2008 experiment, Veropoulidou used 800 snails to dye five 20-by-20-centimeter (8-by-8-inch) pieces of textile, she said.

Who wore purple?

Those who would have worn purple during the Bronze Age remain a mystery, but it is often assumed that the color was only worn by prominent people because of the dye’s complicated process, Veropoulidou said.

At this time there is only evidence that Tyrian purple was used for textiles and wall paintings. However, there is more knowledge about the purpose of the dye in ancient Rome, where the color was reserved only for the elite and royalty, Veropoulidou explained. There are images of Julius Caesar wearing dark purple togas, and during the Byzantine Empire, from 330 to 1453 AD, only the emperor had the right to wear the color.

The newly discovered workshop appears to be on the small side, so it’s possible that the dye was a private supply used by the island’s residents, rather than being sent for trade, Berger added, which would indicate may indicate that the color was for more general use. .

“I think the first thing that caught people’s attention is, first of all, that the color is extremely deep – it was a very vibrant, attractive color – but also that the color could be kept alive and beautiful for a long period of time, perhaps for a long period of time. two, three, four centuries, which is amazing when you think that the way we wash our clothes now, they fade after two or three times we wash them,” Veropoulidou said.

More mysteries behind the hue

During the excavation, the researchers also discovered 2,592 mammal remains, including the bones of young pigs and lambs.

Although the study authors note that they are unsure of the link between the remains and the dyeing process, Berger said this could be evidence of religious sacrifices made to protect the site, due to the importance of the color.

Another theory is that the bones were somehow used to help regulate the temperature needed to get the perfect shade of purple, Melo said. “The knowledge of these guys is amazing, because even for us it is difficult to control the temperature (when making natural dyes). They were able to control the temperature to some extent. Were these bones there to control temperatures? We do not know.”

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com