Cyberspace, which encompasses the Internet and other connected digital technologies, offers enormous benefits, but also poses significant risks as a military domain. This requires the existence of heightened cybersecurity and cyber diplomacy.

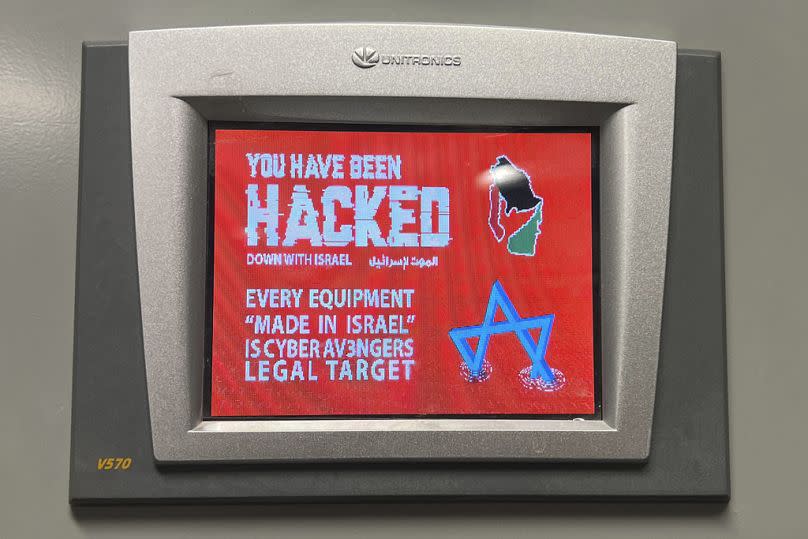

The discussion and regulation of the militarization of cyberspace has gained relevance due to its greater use in modern conflicts. The war in Ukraine is an example of an open military conflict that also takes place in cyberspace.

Historically, arms control has been vital to preventing military escalation. Yet, creating applicable and verifiable cyber arms control measures is challenging due to the unique nature of cyberspace.

A recent analysis, conducted with colleagues from the Technical University of Darmstadt, identifies a number of important obstacles:

What is a ‘cyberweapon’?

A fundamental challenge to establishing arms control in cyberspace is the lack of clear, uniform definitions of key terms. This is particularly relevant because the conventional definition of a weapon does not really capture the characteristic of a cyberattack being used as a “cyberweapon.”

Cyber weapons are typically data and knowledge that can be designed and executed in such a way that they compromise the integrity, availability or confidentiality of an IT system, without the owner’s consent.

For example, some experts we spoke to argued that the concept of a cyberweapon itself does not exist, since a weapon suggests some kind of kinetic, physical use. Cyberattacks exploit vulnerabilities in technology and can lead to physical problems in the real world, but does that mean the trigger was a cyber “weapon”?

This ambiguity makes it difficult to determine what falls under a cyber weapons treaty.

Many everyday technologies, such as computers and USB sticks, have both civilian and military applications.

There is no definitive line that can be drawn between these different use cases; therefore, the products cannot be banned in a fundamental sense for arms control. You can ban landmines or nuclear weapons, but you cannot ban USB sticks or computers.

Moreover, many tools that can be used as cyber weapons are also tools for building cyber defenses or espionage.

Although dual-use has played a role in arms control treaties in the past, the dual-use nature of cyber weapons is now taking on a very different dimension than before.

Verification for gun control one of the biggest obstacles

Finding appropriate verification mechanisms to establish arms control in cyberspace is extremely difficult. For example, it is not possible to quantify cyber weapons. And we cannot count weapons or ban an entire category, as has been the case with arms control agreements for traditional weapons.

Furthermore, cyberweapons can be replicated infinitely and shared around the world at no cost. For example, if you delete code from a device, it doesn’t mean it’s really gone; it could be on a backup system or somewhere else on the internet.

This exacerbates the challenges of establishing appropriate verification mechanisms, as they would need to be extremely intrusive. Many states may be unwilling to engage in an intrusive verification process, as they would need to provide insight into their own cyber defenses, with the potential for these insights to be abused to spy on their vulnerabilities.

Cyberattack tools and technology evolve rapidly, often outpacing regulatory efforts. By the time a regulation is agreed upon, the technology may have advanced beyond its reach. This rapid evolution complicates any regulation or verification measures based on the technical characteristics of software.

For example, the code of a cyber attack is usually based on continuous software developments that are adapted for specific goals and tasks.

This means that the code will change and evolve incredibly quickly. The variation will be extremely high and future cyber attacks will always be different from previous attacks.

Furthermore, because of the dual use and the fact that most cyberspace infrastructure is privately owned, the private sector would need to be involved and engaged for arms control to be effective.

We must address the harmful acts ourselves

Political will is crucial to establishing arms control measures. States that recognize the strategic value of cyber tools by building their capabilities in this area may be reluctant to commit to new treaties that limit their potential benefits. The current geopolitical climate further complicates efforts to achieve broad consensus.

Literature research and expert interviews show that traditional arms control measures cannot simply be applied to cyber weapons. Instead, the focus should be on prohibiting specific malicious actions. This approach allows for agreements that can adapt to technological advances and the dual-use nature of cyber tools.

Since 2015, international negotiations within the United Nations (UN) have led to the establishment of 11 norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace. These norms aim to limit state actions and define positive obligations.

However, these norms are voluntary and non-binding, leading to frequent violations. The challenge is to make these norms more binding and hold states accountable for malign actions.

Attribution, the process of (publicly) assigning cyber operations to specific actors based on evidence, is a crucial tool in this regard. Once considered too complex, attribution is now increasingly feasible and could serve as a basis for approving the use of cyber weapons rather than the weapons themselves.

This should therefore be taken as a starting point for finding creative alternatives and solutions for arms control in the traditional sense. Considerations towards an international mechanism or institutionalization of such processes thus appear to be interesting.

Helene Pleil is a research associate at the Digital Society Institute (DSI) of ESMT Berlin.

At Euronews, we believe that all opinions matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.