-

For the first time in 221 years, two broods of periodical cicadas appear at the same time.

-

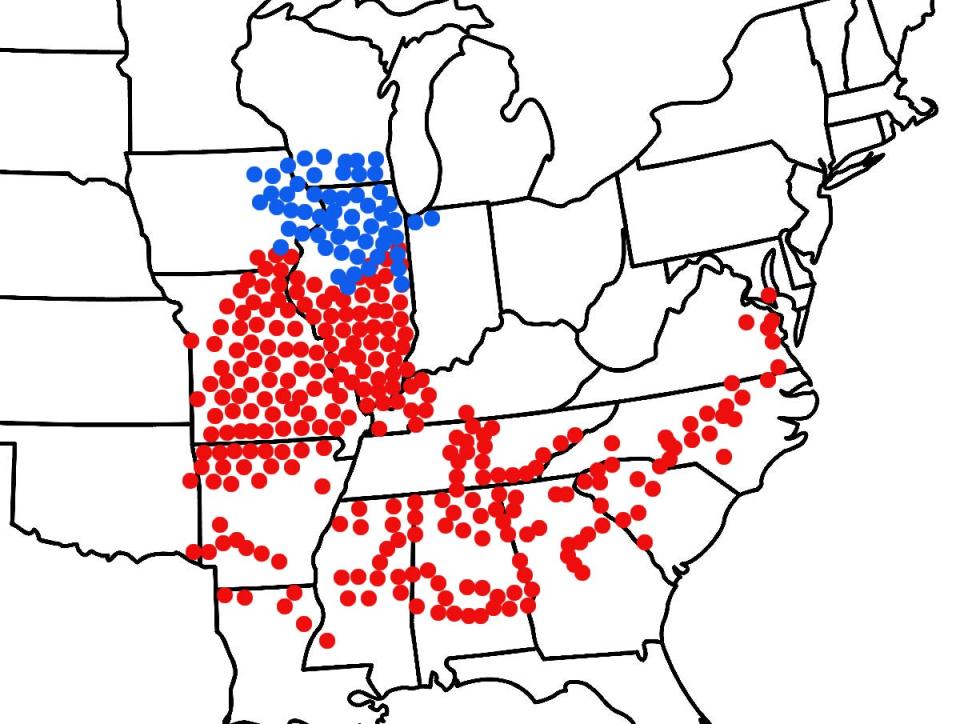

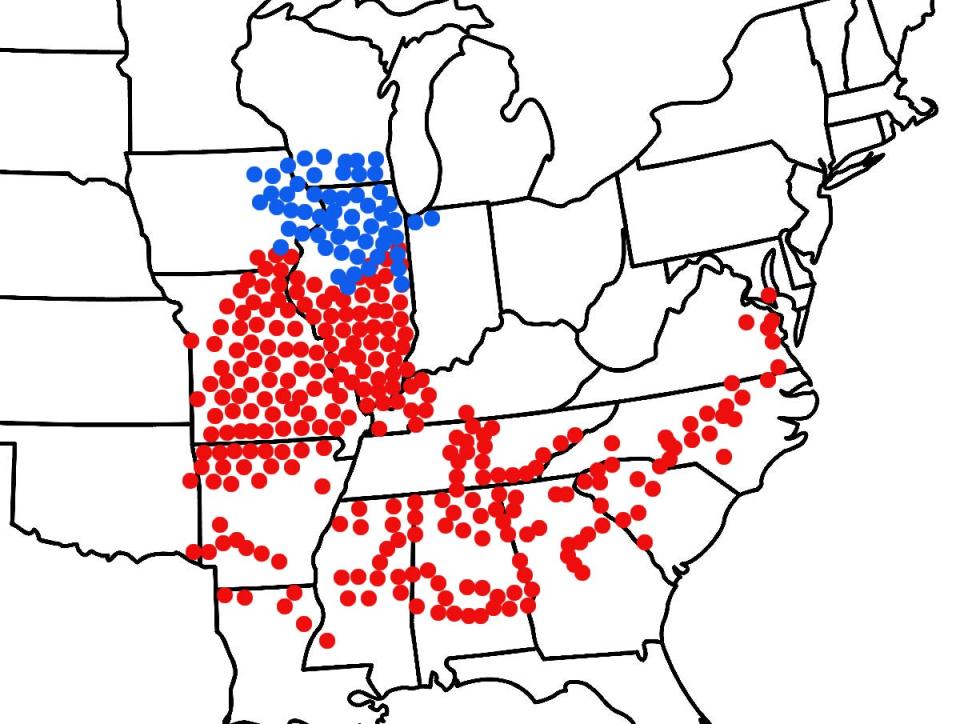

Broods XIII and XIX overlap in a small part of Illinois, around Chicago.

-

People can help scientists monitor these insects using citizen science apps.

2024 is the year of the cicada apocalypse.

That’s because two broods of periodical cicadas – Broods XIII and XIX – will emerge from their underground lairs simultaneously for the first time in 221 years.

The last time the two groups worked together, Lewis and Clark began their trek through territories recently acquired through the Louisiana Purchase, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison, and Thomas Jefferson became president.

There is a hype about red-eyed insects reached social mediawhere commentators are both bewildered and excited about future encounters with the twin cicada swarms.

“What sign of the apocalypse are we at again?” one user joked on Instagram.

“Leap year, crickets AND an election year? I don’t know if I can do it,” said one commenter on Instagram.

Fortunately for those preparing to spend spring in their basement, the two broods of periodical cicadas won’t overlap much.

Brood XIX will appear primarily in the Southern states, while Brood

One part of Illinois will see an overlap. That’s where cicada hunter Gene Kritsky, along with his wife Jessee Smith, will go this year — along with many other cicada sites — to chronicle their appearances.

“I’ve been mapping cicadas since 1976. That’s how old I am,” Kritsky told Business Insider. “I’m going to the Chicago area – I’ll be there the first weekend in June – where I’ll be giving talks and doing some hiking in the Lake County Natural Area.”

Kritsky, an author, professor at Mount St. Joseph University and creator of Cicada Safari, an app that crowdsources cicada photos for scientific research, is excited to see cicadas again this year after last year’s stragglers. However, he is very aware of how polarizing the insect can be, both online and offline.

That’s because they appear in their thousands, make a lot of noise, and their crushed remains can even pose a danger to motorists because they make roads slippery. Sometimes they can damage young trees by trying to lay their eggs in them.

However, cicadas are harmless and do not hurt people or animals.

“I’ve helped people plan vacations to where the cicadas pop up,” Kritsky said. “I’ve helped people plan vacations outside of the area where they’re emerging. So there are both extremes.”

Unlike annual cicadas, periodical cicadas spend years in their underground chambers, much like breeding teenagers (is that why they’re called broods?) in cycles of 13 or 17 years. In the case of the next two emerging broods, Brood XIII emerges every 17 years, while Brood XIX appears every 13 years.

There are 15 broods in the US: 12 broods of 17 years and three broods of 13 years. Kritsky said this means that in more recent history there have been other cases of two broods appearing simultaneously.

“In 1998 we had a 17-year-old brood and a 13-year-old brood,” Kritsky said. “So this is happening. It’s probably happened at least a dozen times in the last 200 years.”

However, that doesn’t mean that the periodical crickets – which appear in their millions – aren’t a sight to behold.

The life of a periodical cicada

Periodical cicadas, an insect with red eyes, a black body and orange rings, spend most of their lives just a few inches underground, under trees. It gets a little cold at that depth, around 56 degrees Fahrenheit, so they don’t move much. The cicada nymphs tunnel around and feed on the sap of tree roots. Kritsky told BI that many live near parks and cemeteries in suburban areas because they are attracted to “mature trees, in full sun, with low vegetation.”

This is their life for 13 to 17 years until it is time to reproduce. Scientists don’t know exactly how they determine how many years have passed, but there is evidence that they keep track of the seasons by detecting the flow of sap in the trees.

When the time comes, they emerge in late spring when soil temperatures reach about 65 degrees. This happens at different times and in different locations between the end of April and the beginning of June. Depending on temperatures, Brood XIII could appear in early June or late May, Kritsky said. Brood XIX, also known as the Great Southern Brood, could be released as soon as April.

The crickets usually first appear at night. The males will find their way outside during the first few days, climbing trees, and the females will follow later. The first days of freedom are about shedding their old exoskeleton and hardening their new exoskeleton to become adults. Then it’s time to mate.

To attract a mate, male crickets use an organ in their body that creates a sound similar to a screeching buzz. This is perhaps what people most recognize about crickets, because they can get loud, like a loud lawnmower.

If a female joins in, they mate. The female then searches for trees in brighter areas, finds small twigs at the end of the branches, cuts them and lays between 400 and 600 eggs. When they run out of space on one branch, they fly to another, Kritsky said.

Once they complete their mission, adult crickets die quickly. After about six weeks, the eggs hatch from the trees, fall to the ground and burrow into the soil to restart the cycle.

Crowdsourcing has changed the cicada game

Before Cicada Safari’s existence, Kritsky said the highest number of records about crickets was about 8,000 records of cricket locations. His research teams have received more than half a million records since 2019, thanks to the thousands of cicada enthusiasts who submitted photos. Kritsky said it has helped cicada scientists understand the distribution of periodical cicadas more accurately.

“We found data from areas where crickets have never been reported before, not because they weren’t there, but no one knew who to report it to,” Kritsky said.

The app has also helped researchers discover new patterns of emergence. Smaller numbers of periodical cicadas normally appear four years earlier, a phenomenon scientists are still trying to figure out. More recently, however, scientists have noticed that crickets emerged a year earlier.

In 2023, researchers like Kritsky were able to capture these patterns – which could indicate shifts caused by climate change – thanks to observations from citizen scientists.

But more than that, Kritsky said, the app has encouraged people to connect with family and friends through crickets.

“You can mark your life by the emergence of cicadas that you remember,” Kritsky said.

Read the original article on Business Insider