Scientists say they still don’t understand how much damage the Maui wildfires have done to corals and the marine ecosystem off the island’s west coast.

After an initial blaze ignited into a week-long series of wildfires, the needs of people on land remained the priority in the months that followed. At least 100 people were dead or missing, and entire neighborhoods were wiped out, leaving few resources available to monitor the marine environment, researchers told ABC News.

“In the beginning, we almost felt inappropriate talking about the research we were doing because there was so much pain on our island,” Liz Yannell, program manager at Hui O Ka Wai Ola, a citizen science network on Maui, told ABC News.

MORE: Maui wildfires one year later: Key developments in cleanup and recovery

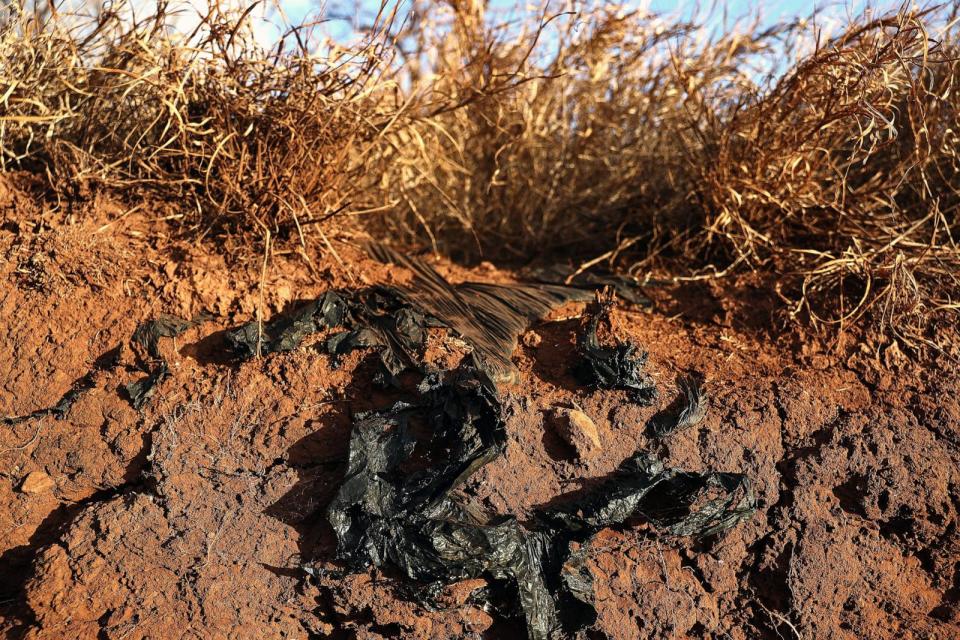

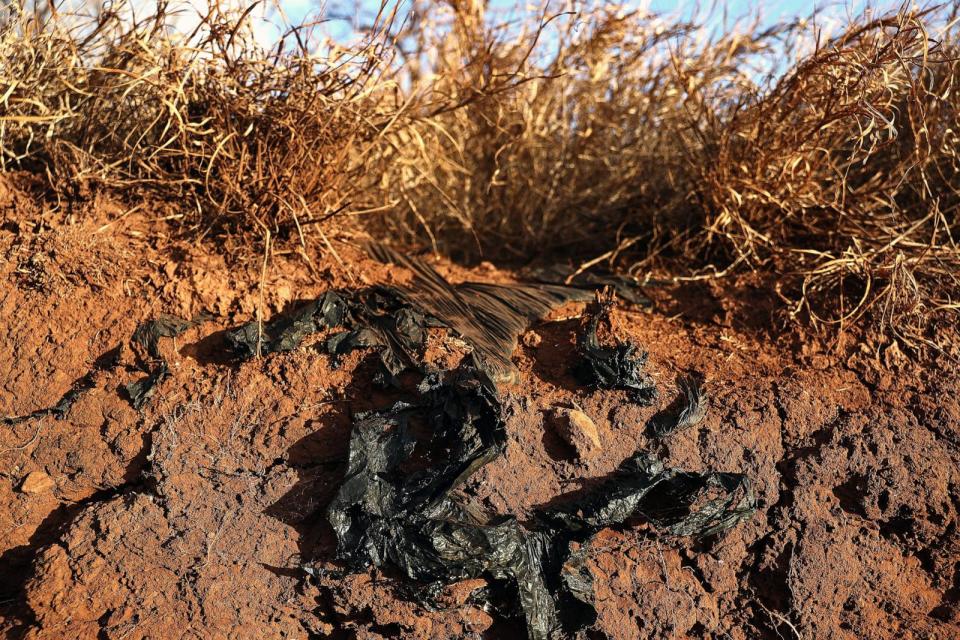

The immediate concern for the coastlines was the trash that washed into the waters off the coast, as well as ash and other toxins that affected air and water quality and were carried by the smoke, John Starmer, science director for the Maui Nui Marine Resource Council, told ABC News. In addition, the boats that sank leaked fuel and other chemicals into the Pacific Ocean.

The murky water appeared so dangerous that “nobody wanted to go in” to investigate, Starmer said.

“It was difficult to really get a sense of the circumstances,” he said.

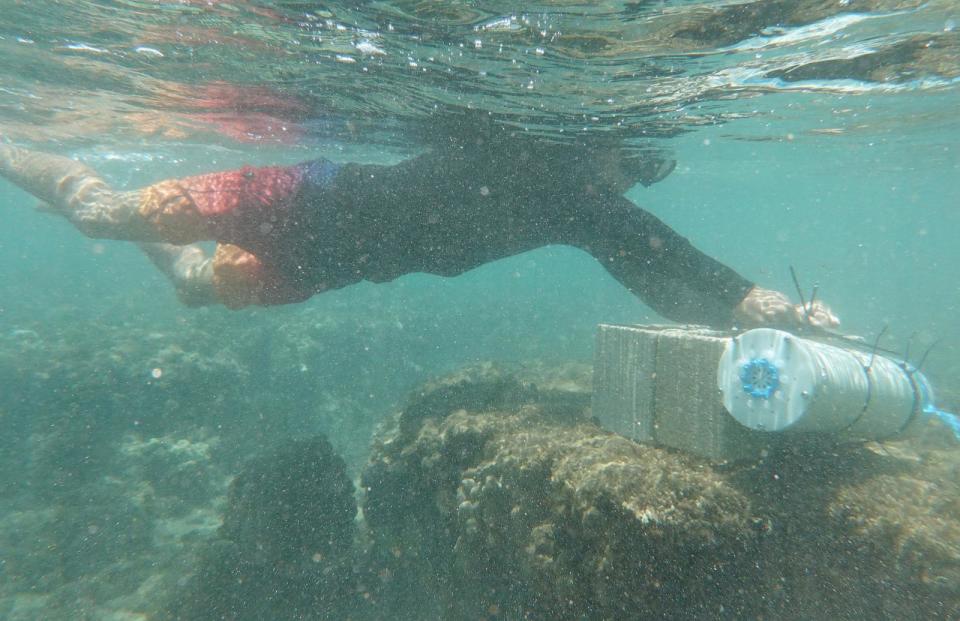

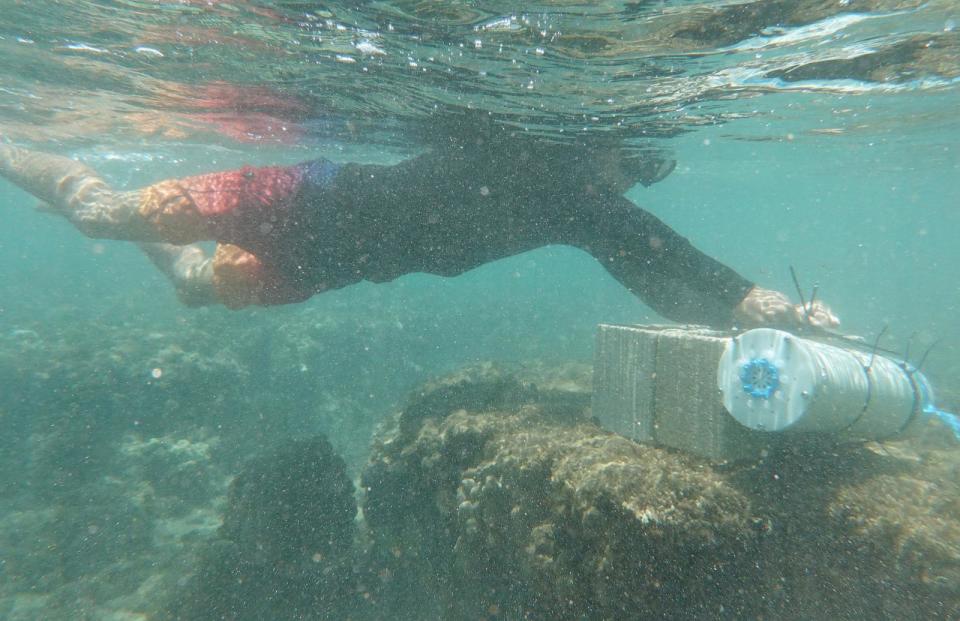

Researchers initially used a remotely operated vehicle and artificial intelligence to map the offshore reefs. As concerns about contaminant levels in the water eased, researchers began conducting dive surveys. They tested the water quality of a series of samples for metals and other general water quality parameters, such as nutrients, Andrea Kealoha, an assistant professor in the Department of Oceanography at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, told ABC News.

From the start of the firefighting effort it was clear that the clean-up effort would be long, difficult and arduous and that the fires would have lasting effects on the island’s environment.

MORE: Native Hawaiians Fight for Control of Maui Water Rights in Wildfire Cleanup

When the fires broke out, environmentalists feared the first major rains of the rainy season, which would normally fall in November, just three months after the fires, Yannell said.

But Mother Nature was on Maui’s side this time, as the “first flush” didn’t happen until Jan. 10, giving emergency responders much more time to clear the piles of debris, she added.

Still, despite the delayed rainfall, huge plumes of sediment washed over the reefs when the first major storm passed, Starmer said.

“Once it gets into the water, there’s really nothing you can do about it,” he said.

MORE: The emotional toll of clearing debris from Maui wildfires

According to researchers, metals such as copper have been found in the water. Copper is often used to prevent barnacles from growing on boats.

Despite the widespread devastation and massive cleanup operation, there is no evidence that corals or the marine ecosystem as a whole in West Maui were physically damaged by the fire, the researchers said.

Visually, there are no consequences, Kealoha said.

“That doesn’t mean we’re there yet,” Starmer said.

MORE: Why Climate Change Can’t Be Entirely Blamed for Maui’s Wildfires

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography has set up a monitoring station at Launiupoko, just south of Lahaina and adjacent to the landfill that handles waste from the wildfire. The move comes amid community concerns that the landfill could harm nearby reefs at Launiupoko and Olowalu, the marine research agency announced last week.

Researchers caution not to confuse the current lack of evidence with the possibility that West Maui’s marine ecosystem will remain unscathed by the wildfires in the long term.

Ongoing testing is beginning to provide evidence of chemical contamination and other residual environmental impacts from the fires, Starmer said. The toxins are likely to bioaccumulate and move up the food chain, with some fish testing positive for PCBs and PAHs — industrial chemicals — he added.

Complicating monitoring efforts is the fact that wildfires — particularly urban fires that carry man-made chemicals — rarely occur near reef systems. As a result, researchers don’t know what to expect. They hardly know what to look for, they said.

“There is no substantial research that is easy to find about urban fires near coastal waters and what that means for a coral reef ecosystem that is already so fragile and struggling,” Yannell said.

MORE: The perfect storm of weather that led to Maui’s devastating wildfires

Coral reef systems worldwide are struggling due to stressors such as pollution and rising ocean temperatures. Overall, the long-term health of the marine ecosystem in West Maui is unclear and marine researchers will continue their quest to understand how corals have been affected and try to prevent toxin-contaminated runoff from reaching the ocean.

But there are signs of a recovering marine ecosystem. Humpback whales have returned to the region on their annual migration routes, monk seals have taken up residence on their favorite beaches and crabs have reclaimed their favorite spots along the coast, Yannell said.

One of the positives of the aftermath of the wildfires is that the reefs have had “a break from people,” such as tourists and surfers, similar to what happened during the isolation measures of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kealoha said.

“Although the world above water has completely changed, the reefs look relatively healthy and are comparable to pre-fire coral cover records,” Orion McCarthy, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said in a statement. “It’s too early to say there’s no impact.”

How Maui’s Marine Ecosystem Is Doing One Year After Wildfires originally appeared on abcnews.go.com