I made an accidental and astonishing discovery while studying the movements of sharks off the coast of Jupiter, Florida. I wanted to document the migration routes of silky sharks, named for their smooth skin. Instead, in a story full of twists, I documented the rare phenomenon of a shark regenerating a dorsal fin.

Tagging and then trauma

It all started in the summer of 2022, when my team and I tagged silky sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis) as part of my Ph.D. research. Silky sharks are commonly found in the open ocean and grow up to 3 meters in length. Scientists know that these sharks congregate in South Florida every summer, but where they go the rest of the year remains a mystery—one I was hoping to solve.

Local boat captain John Moore took us to a place where sharks gather. We carefully captured GPS trackers and gently attached them to the dorsal or upper fin of 10 silky sharks.

The tags, which are attached like large earrings, do not hinder swimming and are designed to fall off after a few years. When the tag’s antenna breaks the surface of the water, its GPS location is picked up by above-ground satellites, hopefully revealing details about the shark’s secret life.

I went home to follow their travels from my laptop.

The story took an unexpected turn a few weeks later, when I received disturbing photos from an avid diver and underwater photographer, Josh Schellenberg, who knew about my work.

The photos showed a male silky shark with a large, gaping wound in its dorsal fin, as if someone had taken a cookie cutter shaped like a satellite tag and punched right through it. Josh wondered if this person was one of the sharks in my research.

When placing the GPS tags, I also place a second tag under the dorsal fin of each shark, which has a unique ID number on it, so I could confirm that the injured shark was one from my study, #409834.

I felt a mixture of relief and sadness. Relief that the shark survived this ordeal; sadness about the scientific data that would now remain uncollected.

Silky sharks are commonly caught by local fishermen in this area, but are protected in Florida and illegal to kill or retain. Josh’s photos of #409834 showed several hooks in his mouth, so I knew this animal had been captured several times since my team tagged him.

The way the satellite tag is attached makes it impossible for it to naturally tear from the fin and leave a wound in this form. Why someone cut the shark’s satellite tag off remains a mystery, but perhaps they thought they could resell it or possibly wanted to interfere with the investigation. I never expected to see that shark again.

The return of #409834

Flash forward to a year later, the summer of 2023. I received several photos of silky sharks from John Moore, our boat captain, who is also an avid diver. John was looking for one of our sharks making their seasonal return to Jupiter. In the many shark photos he sent, I saw a silky shark with an oddly shaped dorsal fin.

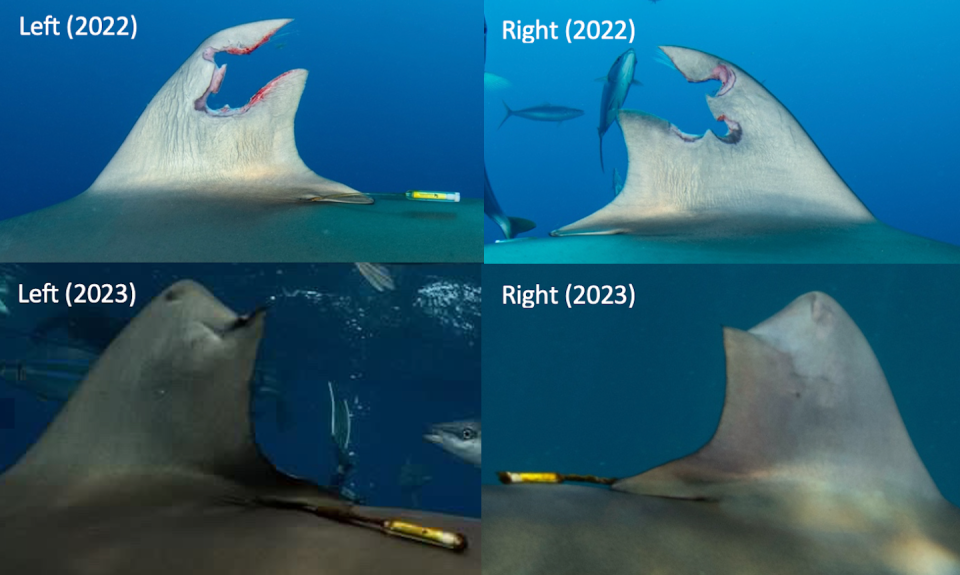

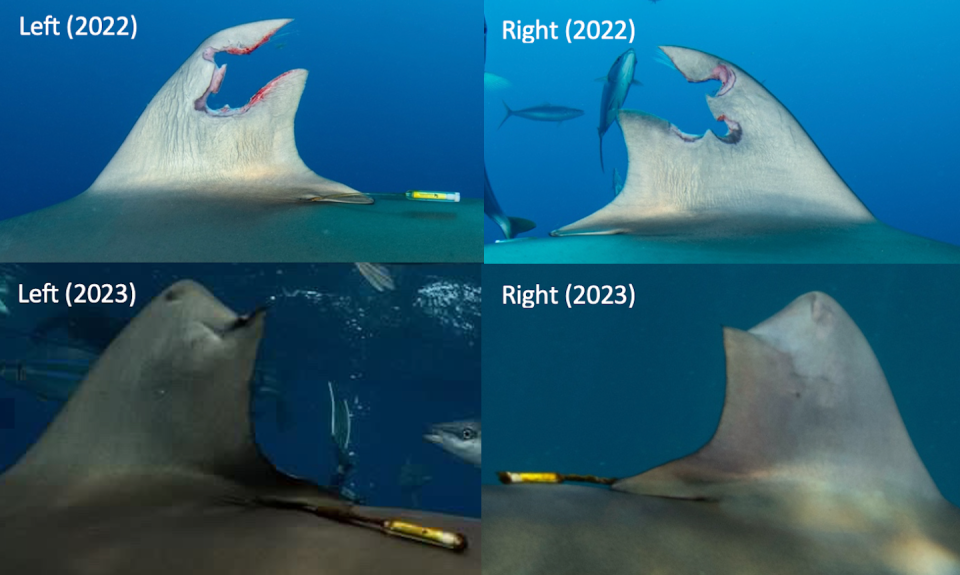

I immediately knew it had to be #409834 from last summer. A few days later, John was able to get close enough to photograph the ID tag to confirm my suspicions. Josh Schellenberg also saw and photographed #409834. Using the photos from both John and Josh, I was able to compare the healed dorsal fin to the freshly injured one.

I didn’t expect to make a groundbreaking discovery. Simple curiosity led me to analyze the photos. But the revelation was astonishing: not only was the wound completely healed, but the 2023 dorsal fin was 10.7% larger than after the 2022 injury. New fin tissue had regenerated.

My analysis showed that within 332 days the shark had regenerated enough tissue that its dorsal fin was almost 90% of its original size, growing back more than half of what was cut off by 2022.

The dorsal fin, crucial for balance, control and hydrodynamics, is critical for a shark to hunt and survive. Seeing no infection or signs of malnutrition in #409834 indicates an extraordinary feat of endurance.

Scientists know that sharks have an incredible ability to heal, but the mechanisms behind these observations are still poorly understood. Although limb regeneration has been extensively documented in other marine animals such as starfish and crabs, there is only one other documented case of dorsal fin regeneration in a shark: a whale shark in the Indian Ocean that regrew its dorsal fin after a boating accident in 2006.

400 million years of resilience

There’s a reason why sharks have been on Earth longer than trees and have survived multiple mass extinction events that wiped out other species. They are the product of 400 million years of evolutionary adaptations that demonstrate their remarkable resilience and have prepared them for survival.

It’s a major scientific advance to be able to pinpoint an ability that makes them so resilient, especially since scientists are still wondering where silky sharks spend most of their time in the Atlantic Ocean.

One person’s attempt to undermine shark science and harm a shark ultimately proved futile. Instead, the shark’s toughness got the better of him, leading to an astonishing discovery about this species. This story also shows that there are countless individual people, including scientists like me and shark enthusiasts like Josh and John, who share a genuine love and respect for these animals.

While I will never know for sure where #409834 will spend the rest of the year, I hope he continues to return to Jupiter each summer so we can further assess his progress. Based on the recovery rate calculated in my research, we may see his dorsal fin grow back to 100% of its original size.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Chelsea Black, University of Miami

Read more:

Chelsea Black does not work for, consult with, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.