The city is not allowed to fall, which is a shame, because the city is busy falling. Oh, things were good there for a while: an egalitarian oasis among the glaciers, a frozen highland of organized labor, respect for the environment, and an aggressive equal pay policy where the lowest layabouts earned the same wages as our most brilliant scientists.

But the problem with socialism is that eventually you run out of coal? It’s that you run out of coal. And then the problems begin. The ice I had kept at bay crept into my infirmaries and nurseries, the machines that reproduced me stuttered and failed, and my subjects split into two factions: those who wanted my head, and the dead.

Frostpunk 2 is just as brutal as its predecessor, but wait, it’s harder. In the first game your authority was virtually unchecked. Passing laws was a matter of decree: you waved your hand and entirely new social orders emerged.

But those were the old days. Back then, you played the role of the Captain, the undisputed master and commander of the post-snowpocalyptic society of Frostpunk the First. “What I say goes” was the name of the game.

But now the Captain is dead and you play his chosen successor, the Steward. Worse still, the scum has gotten into this dangerous new thing called democracy, basically a vast conspiracy to make your job harder, and doing things like adding sawdust to everyone’s daily meals or harvesting their organs after death now requires a lengthy conversation with the city’s factions and a tense mood in the parliament.

Pure ideology

“Frostpunk 1 was an apocalyptic game, where the world was ending,” says Frostpunk 2 co-director Jakub Stokalski. The question was how we could ‘survive nature’. By the time of the second game – where your city starts out as an already sprawling metropolis – that question is pretty much answered and the population is looking forward to it. “These people, shaped by this ordeal, are now looking for a future for themselves. They get different ideas for this future and are pulled apart.”

“It’s not nature that’s your worst enemy, it’s human nature.”

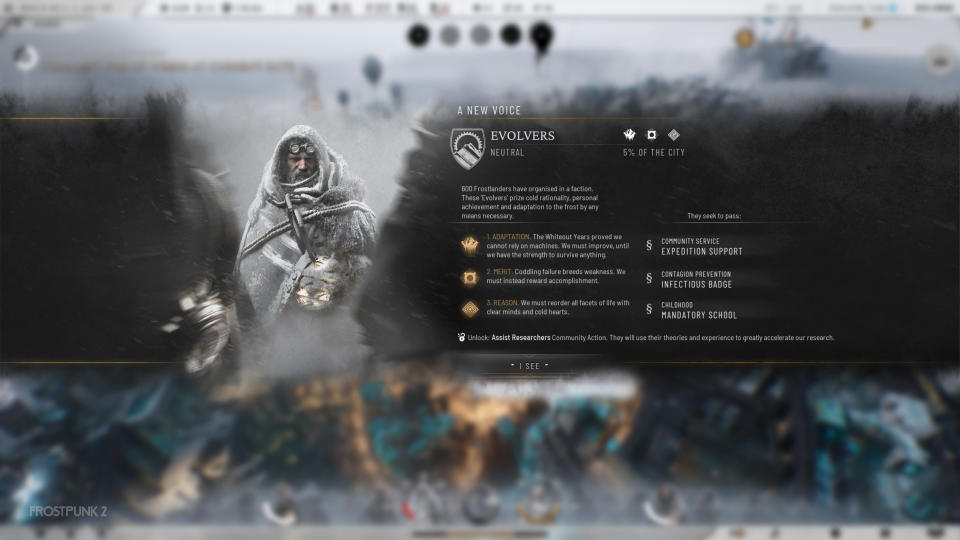

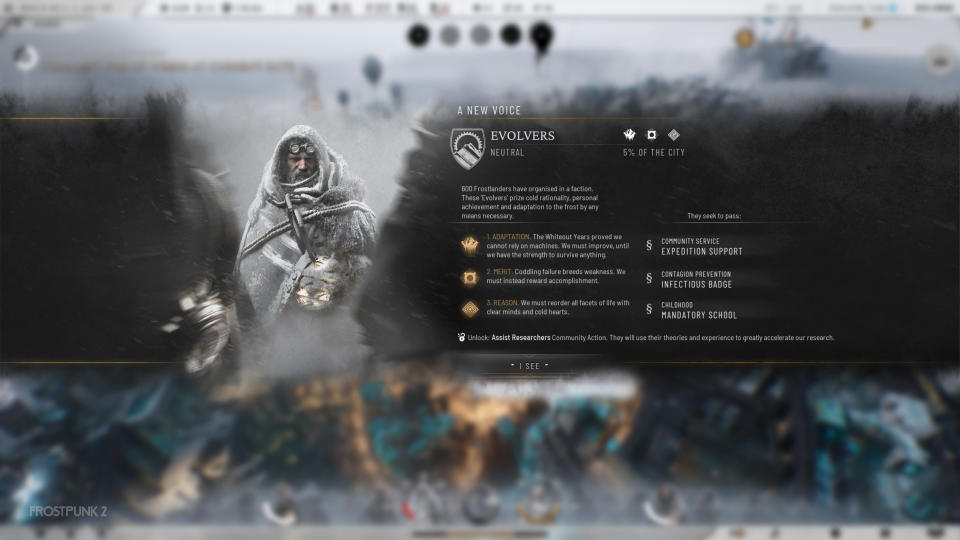

These “different ideas for this future” are mechanically implemented by the game’s faction and community system, a row of portraits at the bottom of your screen that represent the many diverse points of view of your society, and which align with the binary concepts of Adaptation vs. Progress, Merit . versus equality, and reason versus tradition.

In my game – which, I must emphasize, has never worked out at far due to the ‘running out of coal’ – those groups were divided into Frostlanders (hardcore adapters), New Londoners (tech-minded progress types) and the Stalwarts, the Captain’s old hardcore supporters who want to conquer the frost with technology and take tough action against anyone who thinks differently.

“These people, shaped by this ordeal, are now seeking a future for themselves”

They all have their own opinions of you, and the communities can spawn factions, smaller but more dedicated cadres determined to push certain ideologies or policies. I’ve only encountered one during my playthrough – a cabal determined to reverse my policies and implement a more meritocratic society – but Stokalski assures me that it can get “busy” and “crazy” if you let it, especially outside the game’s story mode.

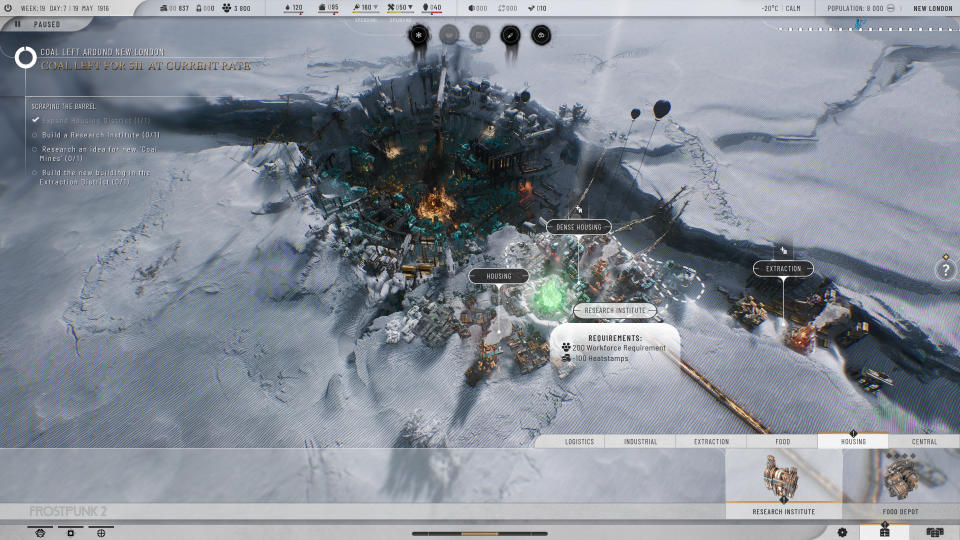

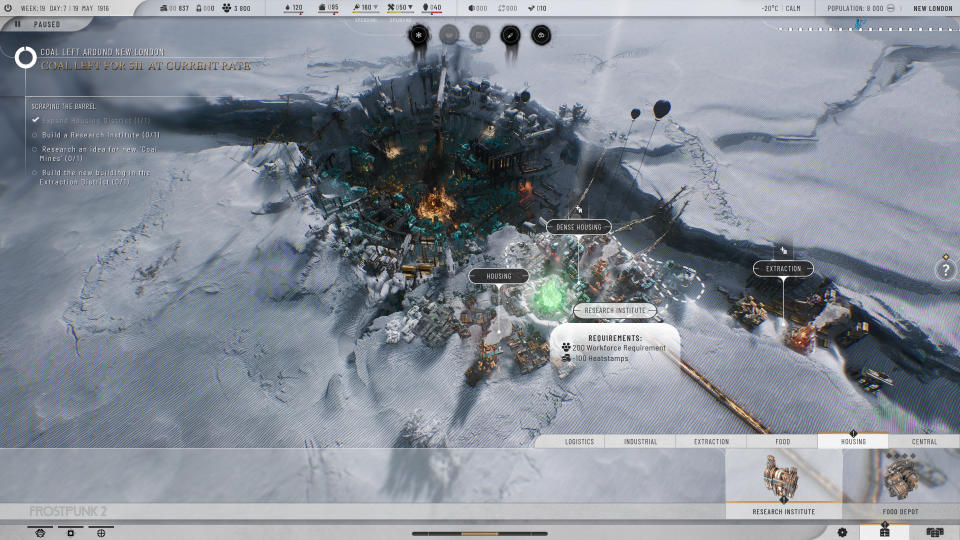

Anyway, who cares what the factions think? I knew what my goal was from the start. A great objective icon declared that I had 523 weeks of coal left, a time when it was essential that I find some kind of new energy source. I also had a housing crisis and a health care shortage, and a lack of consumer goods had created an epidemic of crime on my streets.

Play to the basics

It was all so clear: the conditions were ripe for communism. Not just communism, actually. Turbo communism. A big leap to the final phase of history. A glittering ice city where war and class were scary stories for the children.

All I had to do was ram my favorite policy package through parliament, and that’s where those communities and factions come in. The seats (and votes) in Frostpunk 2’s parliament are occupied by those groups, and they all have their own opinions on the various laws you can propose. My parliament was divided between about ten Stalwarts, about forty Frostlanders, and more than fifty New Londoners.

Inexplicably, none of them were enthusiastic about building the Fifth International. The laws I wanted to pass would ensure that everyone in my city had access to basic needs, regardless of whether they worked or not, and that everyone who did work would earn the same wages, from the garbage collectors to the doctors.

This was a mystery. The Stalwarts hated this. As meritocratic, progress-obsessed reactionaries, they viewed my plans for the city as an insidious communist plot, only two-thirds true. Luckily there were only ten of them, so it wasn’t worth wasting time on them. They went into the dustbin of history.

The Frostlanders and New Londoners were more difficult. Both were more or less split down the middle. When I checked the policy screen to see if my laws could pass, the predicted outcome was ominously uncertain: about twenty against, about thirty in favor, and the rest wildly undecided. I could roll the dice if I wanted – I had passed other laws where the undecided ended up being in my favor – but this was the future of the human race we were talking about. I didn’t want to leave things to chance.

So it was time for slick, Capitol Hill style. I already liked the Frostlanders more than the New Londoners. The reason was Frostpunk 2’s new research system: instead of linearly moving up a tech tree, each community in your city pitches several iterations on an idea and you choose which idea to use. Until now, I was susceptible to the Frostlanders’ more durable inventions, and they adored me in return.

So I made them a promise: I would pass a law they wanted – mandatory civilian support for our wasteland explorers – in exchange for their support for my whole ice communism thing, and so a deal was struck. The law was easily passed, a new world was built, and everyone lived happily ever after.

Frozen

For a while. You’ve got to give me this: things went really well there for a while. Sure, the equal pay law set off a chain of events that had the more governmental and civic elements of my city grumbling and grumbling, but people were – on the whole – quite happy under the new order.

But here’s the thing: that law I promised to pass for the Frostlanders? Well, not everyone was enthusiastic about that either. I had to negotiate through parliament again, which meant more promises, which led to more promises, which led to more promises. Being the terrible politician that I am, I basically moved heaven and earth to keep them all, and the simple process of keeping track of everything I promised to everyone distracted me from the small task of finding a new fuel source for to safeguard our heating equipment.

Everyone was incredibly happy with me and all my promises until the coal ran out, which I more or less stopped paying attention to as I got caught up in a thicket of political maneuvering and ideology. I wasn’t overwhelmed: the game does a good job of not bombarding you with too much information and mechanical complexity, and Stokalski says it’s a conscious effort by the developers to ensure you’re never “taking notes and doing math on the side” . just not to die’ – I had simply become wrapped up in ideas without paying much attention to material reality.

So the generator beeped for the last time, the frost built up in our infrastructure, and all the happiness meters for the groups that were oh-so-happy with me went to an angry, empty red. It wasn’t long before I was removed from power and my beautiful, frozen Soviet went the way of the Paris Commune.

But for a moment, a brief, shining moment, we had our glittering ice city.

The post-post-apocalypse

So Stokalski is right – which I guess isn’t surprising considering he co-directed the game – Frostpunk 2 is a few steps higher on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. If the first game was about the post-apocalypse – scraping together the literal necessities of life – then this game is post-apocalypse. That. It’s about figuring out what’s next after the entire world is destroyed, although even if the food and coal issues are resolved for the time being, they always threaten to become a problem again.

And so far? I’m excited. From my time with the game, Frostpunk 2’s political elements feel like a natural evolution of the first game’s relatively rudimentary Discontent/Hope and Order/Faith systems, forcing you to think about what your citizens want and don’t want only what they need. Success is no longer just a matter of having enough food to survive a whiteout, it’s a much broader category. This also applies to failure.

Frostpunk 2 releases on July 25 on Steam, GOG and Epic.