Sophie Kastner is a composer who has translated the unlistenable into songs and converted nuanced data from the heart of our Galaxy into the notes of a dissonant symphony.

“It’s like writing a fictional story based largely on real facts,” she said in one rack.

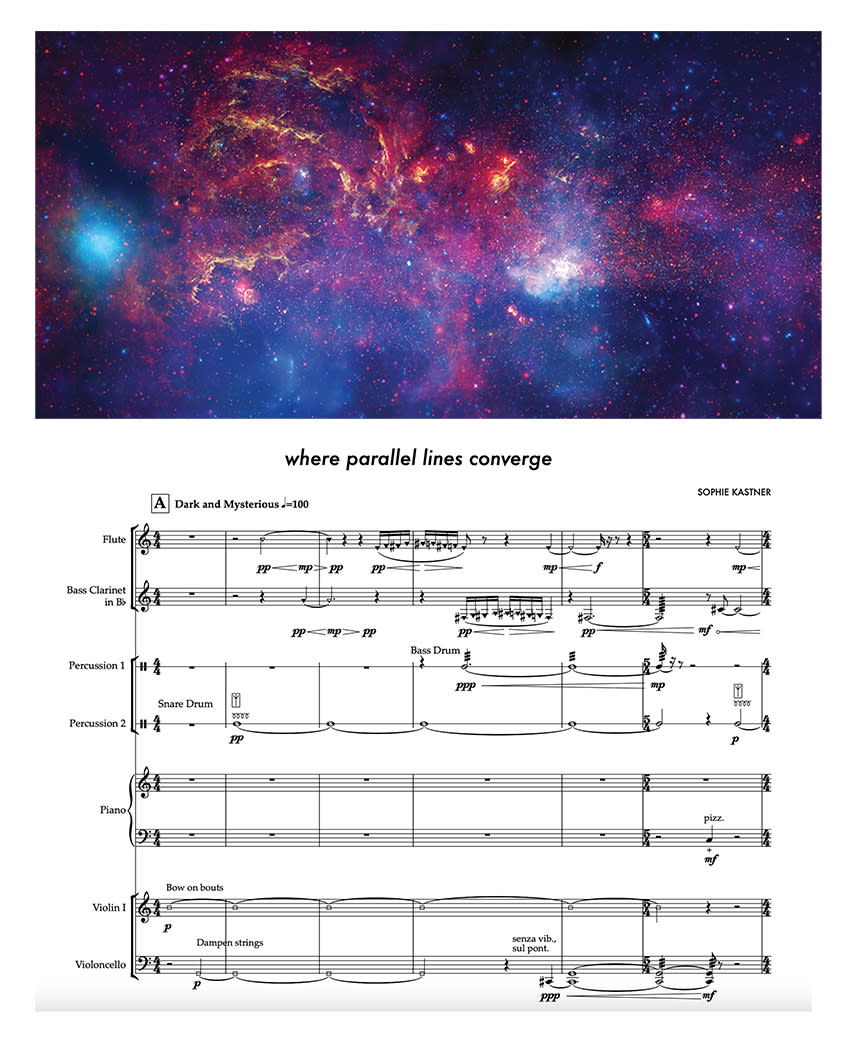

Her piece ‘Where Parallel Lines Converge’ is based on a specific portrait of the central region of our own galaxy, aptly known as the Galactic Center. Physically viewing this image can be a bit disorienting. Are captured in a variety of light wavelengths – X-ray, infrared and optical – by several powerful deep space imagers – NASA’s Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer telescopes. As such, there are countless random swirls and streaks that represent stunning entities in the area, such as bright gas bubbles and luminous star explosions, thick streaks of dust and glowing nurseries of stars.

So instead of trying to make sense of this sonically Composite image from 2009 overall, Kastner decided to focus on three key elements. The first is a binary star system visible in X-ray wavelengths, indicated by a bright blue sphere on the left of the image; the second is the group of curved filaments we see; and the third is the largest of them all: the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* that lies in the heart of us Milky Way. “I wanted to draw the listener’s attention to smaller events within the larger data set,” Kastner said in one Overview of the composition.

But let me take a step back for a moment. You may be wondering: what does this translation actually mean? How can telescopic data be turned into the soundtrack of the universe? As the saying goes, “In space no one can hear you scream.”

However, someone can look at your scream and interpret it.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope could soon solve the mysteries of the heart of the Milky Way

In a sense, sound waves can be thought of as vibrations that propagate through atoms and molecules floating in the air. On SoilThere are many different things in our air: for example, the waves associated with a knock on your door can travel through the air from your home to your ears. But in space there is no ‘air’. It’s a vacuum.

If you were to shout into space, the sound waves you create would actually have nothing to vibrate, so someone standing a few feet away wouldn’t hear you. Even if the Galactic Center were filled with incredible sounds, we wouldn’t be able to hear them unless there were enough surrounding atoms for the sound waves to propagate through. And more often than not when it comes to space objects, there aren’t enough atoms.

The “sonification project” at NASA Chandra X-ray center is an organization dedicated to overcoming this hurdle, with the aim of bringing a different human feeling to space exploration.

Just as scientists use data from The organization has already done this with quite a few space wonders, such as the supernova remnant Cassiopeia Aa set of galaxies known as Stephan’s Quintet and the Carina Nebula as evidenced by the pioneers James Webb Space Telescope.

Sonification efforts like these are especially praised by the scientific community, because “listening” to an image in deep space can allow visually impaired space enthusiasts to make a deeper connection to what lies in the far reaches of space .

To be clear, none of the songs accompanying the aforementioned visuals were created using sounds literally recorded in space. They are audio interpretations of data, just as the images from the JWST are optical interpretations of infrared signals.

“In some ways, this is just another way for humans to interact with the night sky, just as they have historically,” Kimberly Arcand, Chandra visualization and emerging technology scientist, said in the statement. “We use different tools, but the concept of inspiration from heaven to create art remains the same.”

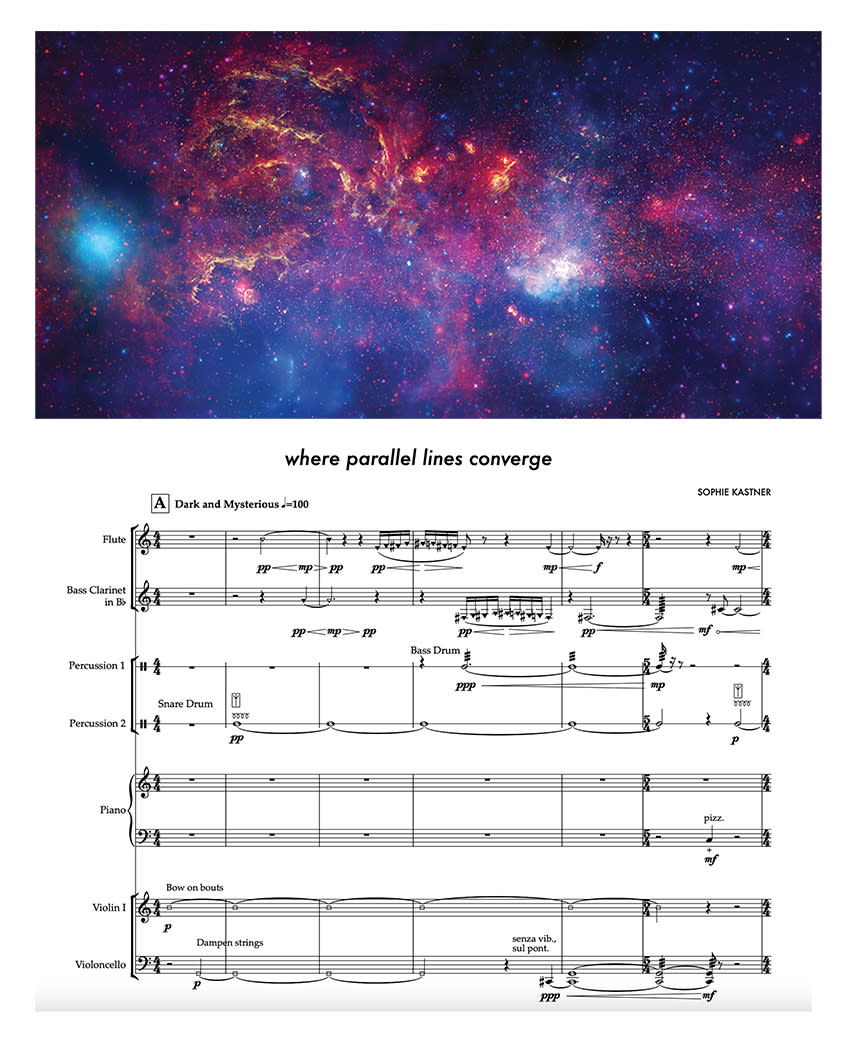

Such an interpretation is exactly what Kastner did with her new composition, truly bringing together the parallel lines of science and song – and the sheet music for the piece is actually available online for anyone to give it a try.

“I like to think of it as creating short vignettes from the data, and approach it almost as if I were writing a movie score for the image,” Kastner said. “I wanted to draw listeners’ attention to smaller events in the larger data set.”

As for what exactly we hear, Kastner’s song is divided into three parts that are “played” from left to right. “The light from objects at the top of the image is heard as higher pitched sounds, while the intensity of the light controls the volume,” says the sonification team. “Stars and compact sources are converted into individual notes, while extensive clouds of gas and dust produce an evolving drone.”

The crescendo of the song occurs when the composition hits the bright area in the lower right of the image. This is where Sgr A* resides and where clouds of gas and dust shine brightest.

“I approached the form from a different perspective than the original sonifications: instead of scanning the image horizontally and treating the x-axis as time, I instead focused on small parts of the image and created short vignettes that corresponded with these events, approaching the piece as if I were writing a film score to accompany the picture,” said Kastner. A more detailed overview of the composer’s notes can be found here.

However, this is not to say that scientists have never tried to improve on the literal waves recorded in space. Remember when the general lack of air in space means that sound waves can’t vibrate properly? Sometimes there are things that can spread these vibrations.

For example, last year scientists determined that a black hole in the Perseus cluster was surrounded by enough gas that pressure waves emitted from the void created a signature that could be detected by our instruments.

Related stories:

— Hear the eerie sounds of distant galaxies in breathtaking NASA video

— Iconic images from the James Webb Space Telescope turned into music

— Scientists convert data into sound to listen to the whispers of the universe

“A cluster of galaxies… contains large amounts of gas that envelop the hundreds or even thousands of galaxies within it, allowing the sound waves to travel,” NASA scientists had said.

The resulting ripples were translated into an actual musical note, but unfortunately the note was 57 octaves below middle C. That’s far too low for the human ear to perceive. So the team resynthesized the signals to the range of human hearing, 57 and 58 octaves higher. That’s 144 quadrillion and 288 quadrillion times higher than their original frequency.

It sounded exactly like you would expect a black hole to sound.