If you were to stare into the black sky on a clear night, you would expect to see nothing but the beautiful Milky Way stretching above you, with billions of stars twinkling in place.

Instead, you’ll also most likely see an ersatz star break through an otherwise static sky every few minutes, moving silently across the stars.

These are satellites, and there are thousands of them in orbit. When they have outlived their usefulness, most of them will tumble through the Earth’s atmosphere again and burn up.

Scientists are now investigating how this process dumps potentially harmful particles into our atmosphere. And while the exact consequences are still unknown, some are calling it a wake-up call.

‘Rare metals’ in the atmosphere

There are an estimated 11,500 tons of space objects orbiting Earth, including even the tiniest pieces about a millimeter in size (likely collisions with satellites). But there are much larger objects in space, including spent rocket stages and more than 9,000 functioning satellites. More than half of these are SpaceX Starlinks, which provide internet services.

At the time of publication, there are approximately 5,200 Starlink satellites, but SpaceX has plans to deploy more than 42,000.

This image shows Starlink satellites shortly after they were launched into space in 2019. (SpaceX)

And it’s not the only company planning to launch these “mega constellations” of satellites. Companies like OneWeb and Amazon and countries like China all have plans to put thousands more satellites into orbit.

What goes up must eventually come down. In the case of Starlink, these satellites have a lifespan of approximately five years, after which they are deorbited. They then burn up in our atmosphere.

A new study, published last week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, suggests that the particles left behind could potentially damage our ozone layer.

If you have 50,000 satellites, which is a number that a lot of people use, and they are five years older, then 10,000 are coming back in every year. That’s more than one per hour.” -Daniel Murphy, NOAA

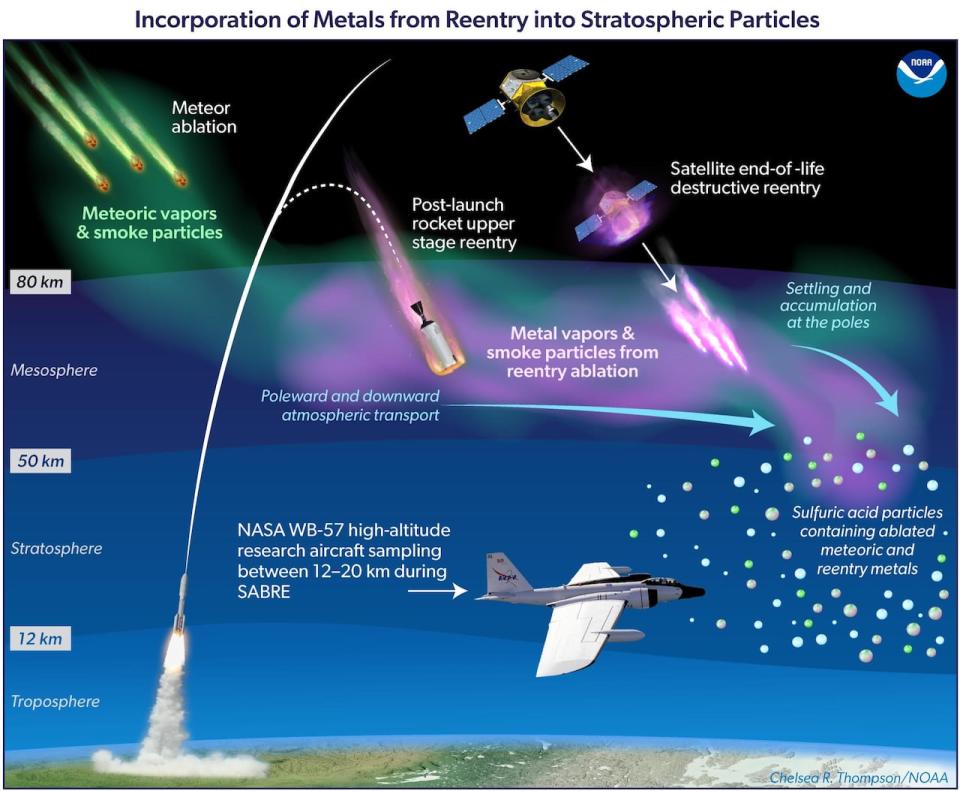

And in a study published in October in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Scientists, several scientists from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) examined particles in the stratosphere.

The researchers were surprised to find a variety of vaporized metals in the stratosphere that they linked to satellites and used rocket boosters.

“It wasn’t actually something we were looking for,” said Daniel Murphy, a chemical laboratory research chemist at NOAA, who led the study.

“When I looked at the data, I started to see not only the metals you expect from meteors, like iron and magnesium, but also strange metals.”

The first of these was lithium, which left Murphy scratching his head, as there is almost no lithium in meteors that burn up in the atmosphere. But then more and more emerged – a total of twenty different metals – including an excess of aluminum, as well niobium and hafnium.

Most rockets contain large amounts of aluminum, while the cones surrounding rocket motors contain niobium and hafnium, along with zirconium.

This illustration shows how satellites burn up in our atmosphere, and shows how the NOAA research plane collected the particles. (Chelsea Thompson/NOAA)

“It quickly became very clear that the source of this was spacecraft re-entry,” Murphy said. “In a way it’s a complete surprise. Nobody thought about it.

“But in a way, that shouldn’t be a surprise, because the aluminum satellites come in and burn up. … It doesn’t disappear from the atmosphere, it has to go somewhere.”

The real surprise was the size, Murphy said. These metals were found in about 10 percent of sulfuric acid particles, which make up a large part of our atmosphere.

“Then you look at the launch rate projections and say, ‘This is something we need to bring to people’s attention,’” Murphy said. ‘It’s a new aspect that people haven’t really thought about yet.

“If you have 50,000 satellites, which is a number that a lot of people use, and they’re five years older, then 10,000 are coming back in a year,” Murphy said. “That’s more than one per hour.”

‘Wake-up call’

Canadian Maya Abou-Ghanem, another co-author of the study, agreed that the findings are concerning.

“Right now, there are really no rules for how many satellites you can return to Earth or deorbit,” she said. “The other thing is that there’s also a lot of unknown science: we don’t really know what the fate of these particles is, what they actually do and whether they are actually dangerous.”

In the newer study, researchers looked at the aluminum oxide metals in the same way in the atmosphere and suggested it could potentially damage our ozone layer, which protects us from harmful radiation.

But they caution against definitive claims.

LOOK | The European space freighter burns up over an uninhabited area of the Pacific Ocean:

“Chemical reactions that occur on the surface of aluminum oxide particles cause ozone depletion,” Joseph Wang, an aerospace researcher at the University of Southern California and corresponding author of the paper, said in an email.

“This study only calculates the amount of aluminum oxide particles. We have not calculated exactly how much ozone will be depleted.”

Their research showed that approximately 30 kilograms of aluminum oxides are produced by the combustion of a 250 kilogram satellite. In 2022, satellites released 17 tons of aluminum oxide nanoparticles into the atmosphere. And this was before the Starlink satellites started disappearing, which only started earlier this year.

Looking at the potential of mega-constellations, they estimate that 360 tons of aluminum oxide particles could be released annually, an increase of 646 percent above natural atmospheric levels.

“So this is a wake-up call,” said Jose Ferreira, lead author of the study and an aerospace engineer and research associate at the University of Southern California. “This is to raise awareness… but we have to be very careful about the message that is being passed on because we need very concrete evidence to draw these kinds of conclusions.”

The researchers are concerned that not enough thought has been given to the potential consequences of our actions when it comes to these mega-constellations.

“When people put something out there will usually be an anthropogenic consequence,” Abou-Ghanem said.

“We’ve seen it all before. So in a way it’s not that surprising that this is happening.”