Mick Moon, who has died aged 86, was the youngest of four associated and internationally respected English painters who, born in the 1930s, came to prominence from the 1960s: the eldest three, in order of age, were Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland and Patrick Caulfield.

They were friends, and all were chosen – despite stylistic differences – by their contemporary, Leslie Waddington, to join his vaunted Waddington Gallery in London’s Cork Street.

Moon’s development as a painter was the most complex of the four. As a drawing teacher – one of his students, (Sir) Christopher Le Brun, became President of the Royal Academy – and artist, he honed his skills as a painter, printmaker, collagist and imprinter to create large paintings inspired largely by later work by Georges Braque.

Braque, in turn, was inspired by his memory of an incident as a soldier in the First World War, when his minder, with some coke and a few thrusts of his bayonet, turned a bucket into a brazier.

“Everything, I realized, is subject to metamorphosis, everything changes depending on the circumstances,” Braque wrote. As co-founder of Cubism with Picasso, from the age of sixty he took his workplace, the studio, as an occasion for, as Moon wrote, ‘immersion in his own private obsessions’.

This obsession with memory and metamorphosis suited Moon’s determined and inquisitive nature.

Moon’s last dealer, Alan Cristea, of the gallery of the same name, and previously as his print publisher at Waddington’s, has described him as “a truly radical artist whose achievements were overshadowed by his own modesty”.

These achievements include Senior Lecturer at the Slade School of Art, 1973-90; a solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery, 1976; first prize, John Moores 12 Exhibition, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 1980; Gulbenkian Print Prize, 1984; and Royal Academician, 1994.

Michael Moon was born in Edinburgh on November 9, 1937. When his father moved to India due to the war, his mother, a gifted amateur artist, moved with her two sons to Blackpool to stay with her mother. The beach became his playground, a memory that contributed to the elegiac seascapes of his last exhibition.

After the war they moved to London, where his now divorced mother worked as a staff artist at the Daily Mirror. The boys attended a private boarding school in Shoreham-on-Sea, West Sussex.

Moon’s first job, thanks to his mother, was for Amalgamated Press, creating letters into speech bubbles. National Service in Germany with the Education Corps was followed by the Chelsea School of Art, where Patrick Caulfield was a fellow student.

His most influential teacher was Michael Andrews, who taught him useful painting techniques, especially masking a surface to focus on one section at a time.

Crucially, he discovered Braque’s studio paintings, which he chose as the subject of his dissertation. In the late Mel Gooding’s monograph, Moon wrote that “an artist’s own concerns” are “very important and more likely to prove valuable” than “an awareness of what is going on artistically, socially and politically.”

He went to the postgraduate Royal College of Art and returned to teach at Chelsea, where Caulfield and Hoyland also taught.

Moon’s first exhibition consisted of paintings, usually done on formica “strips” that were vertically slatted at one-inch intervals and secured in such a way as to give an overall impression of subtly suffused color. They were displayed in a room in Hodgkin’s house in London. Hoyland brought Leslie Waddington to see it, and Moon’s artistic career was launched.

In 1972 he exhibited with Caulfield and Hodgkin at Galerie Stadler, Paris. A year later they were included in “La peinture anglaise aujourd’hui”, Musee d’Art Moderne, Paris. In the same year, Moon was poached from Chelsea by William Coldstream to teach at the Slade School of Art.

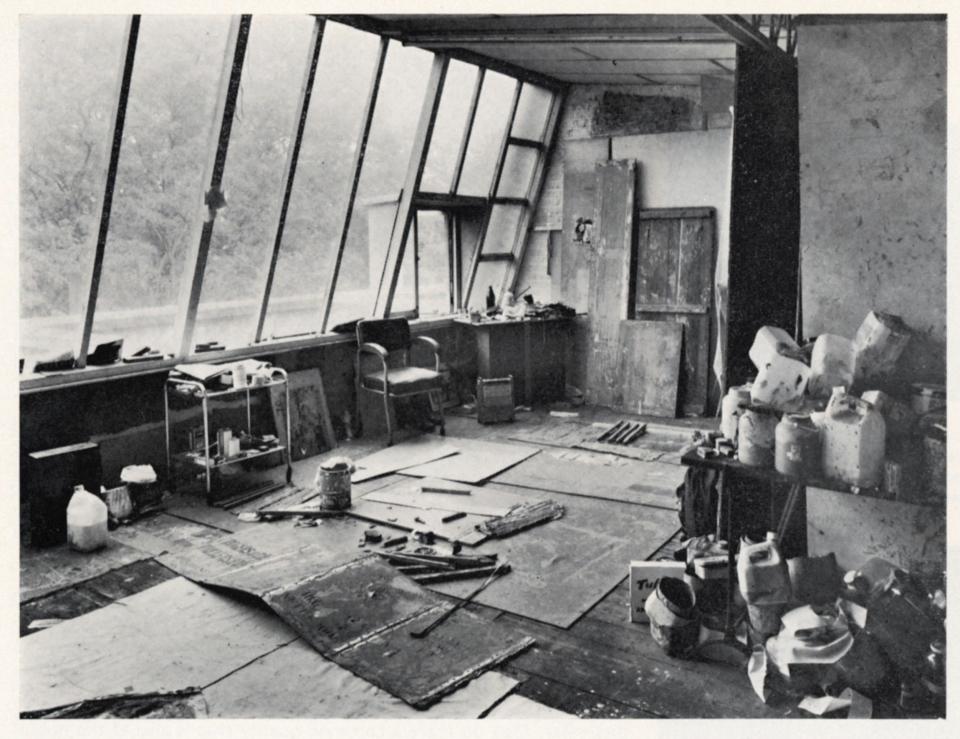

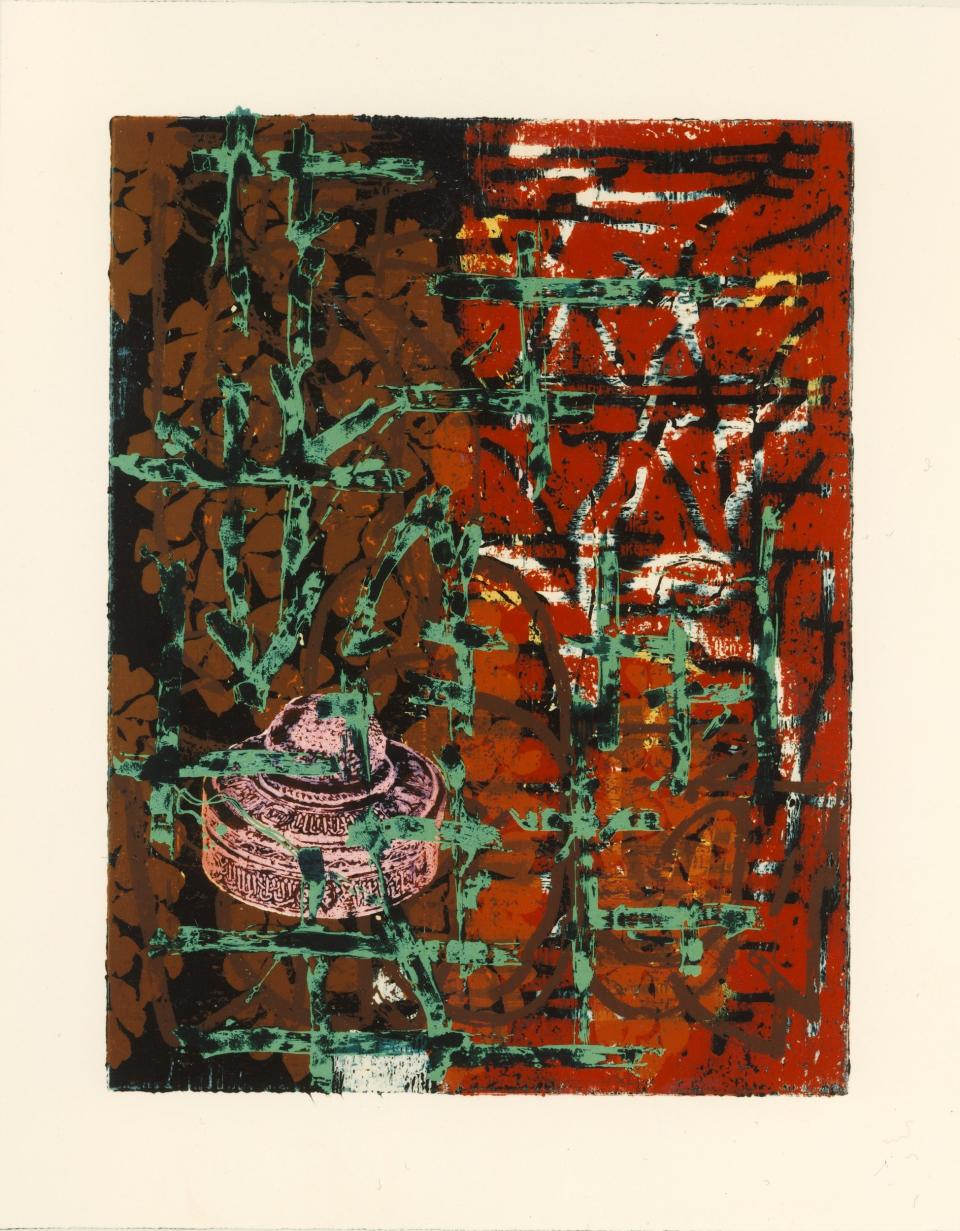

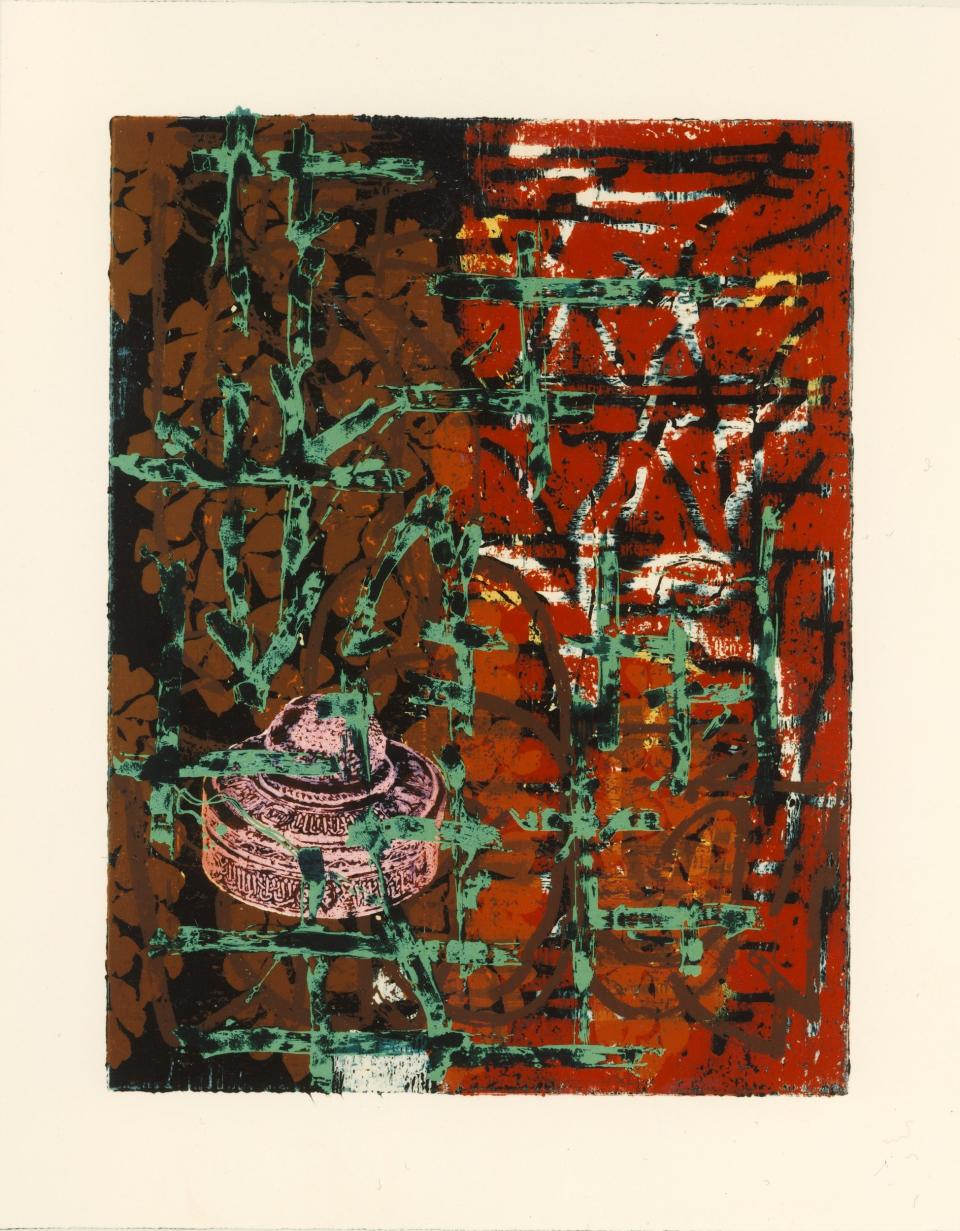

The cool clarity of the comic paintings was replaced by Braque-influenced involvement with the studio and metamorphosis. Moon’s printmaking was a stimulus: process and content were literally fused through prints, in the form of brass friction or monotype printing, of the studio’s contents (particularly floorboards, which provided grainy backgrounds), which became the basis for paintings with concentrated incidents.

They were hung loose instead of stretched, to create unforeseen combinations. These ‘Hanging Paintings’ formed his Tate exhibition in 1976.

Moon’s first marriage, to Carola Kline, had ended in divorce, and in 1977 he married painter Anjum Khan. Visits to her relations in India encouraged him to introduce vibrant colours. He became fascinated by the movement of people, artifacts and goods. Everything was grist to the mill of his studio paintings.

During a 1982 flight with his family, now including his sons Timur and Adam, to artist-in-residence at the Prahran School of Art, Melbourne, the Boeing 747’s four engines failed, choked with ash from a volcanic eruption. A terrifying half hour followed.

Three engines restarted in time for an emergency landing at Jakarta. “There was a lot of kissing on the runway,” was his typically laconic comment. “The Jakarta Incident” is aviation history.

The evolution of the Moon was marked by dramatic changes. In 1992 he exhibited studio paintings which, instead of making prints of floorboards, doors and so on, introduced even more complex Indian and other still life elements. These paintings further expanded Braque’s subject matter, both materially and in scope.

Nevertheless, for all their diversity, Moon’s prints and paintings, as Gooding wrote, “function in both cases as the focal point for quiet and reflexive contemplation.”

After being divorced for the second time, he met his third wife, the Swedish artist Philippa Stjernsward, in 2000. They traveled extensively, including to India, and his satisfaction was reflected in his latest exhibition (Cristea Roberts Gallery, 2019).

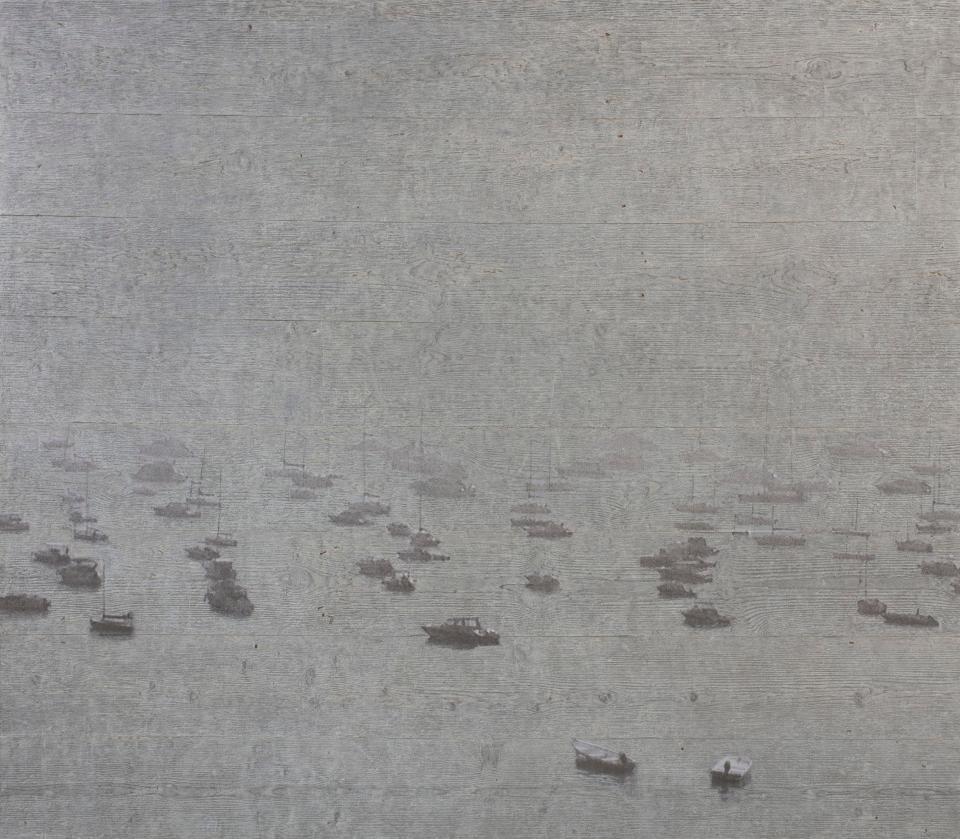

The cool clarity returned, not abstracted but in the form of large seascapes. Free from color and collage, the grain of the printed floorboards evoked the waves and ripples of the seas of his youth. Serene intimations of mortality, content is in one case reduced to a single figure in a distant silhouette; in another, to a monochrome fleet of small anchored boats that fade into misty invisibility; and finally only the tips of their few lights in the darkness of the night.

Mick Moon is survived by his wife Philippa Stjernsward and two sons from his second marriage.

Mick Moon, born November 9, 1937, died February 13, 2024