When you buy through links in our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

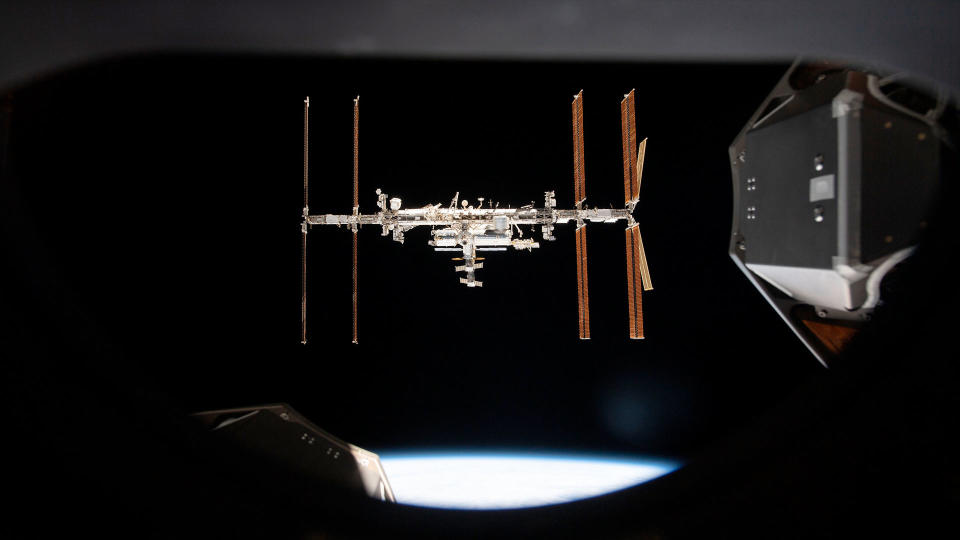

Two years after NASA announced there were no plans to save artifacts from the International Space Station (ISS)’s devastating demise, NASA is now identifying which small parts of the space laboratory should be preserved.

Agency officials at a press conference Wednesday (July 17) released preliminary details about the space station’s end-of-life in 2030 and SpaceX’s choice to build the vehicle that will deorbit the massive complex, allowing it to largely burn up in Earth’s atmosphere and dump any remaining fragments in a remote area of the ocean.

“Twenty-five years out of sixty years [of human spaceflight] “He’s been to the ISS,” said Ken Bowersox, NASA’s deputy director for space operations and a former astronaut who spent 161 days aboard the space station as commander of the sixth manned expedition.

“People often see different things about the ISS that they find interesting, whether it’s the international collaboration, where we’ve worked with so many different countries; whether it’s the thousands of experiments that have been done in microgravity; whether it’s the research with humans; whether it’s the assembly that we’ve done, which showed how you can put together large structures in space; or the exploration operations that we do; or what we’ve learned about the human body and microgravity,” he said.

“All of those things have been important and are preparing us for the future,” Bowersox said. “But 25 years is a long time, and we’re getting to the point where we have to think about what comes after ISS. To prepare for that, we have to plan how we end the ISS program.”

NASA studied lifting the space station to a higher orbit, where it could wait without a crew for a future intact preservation attempt. However, the fuel requirements to “park” the vehicle would be more than twice as much as needed to push it into Earth’s atmosphere and would exceed current launch capabilities. In addition, the complex would be at risk of debris impacts during the years it would be in motion, potentially leaving it stranded or, worse, in pieces.

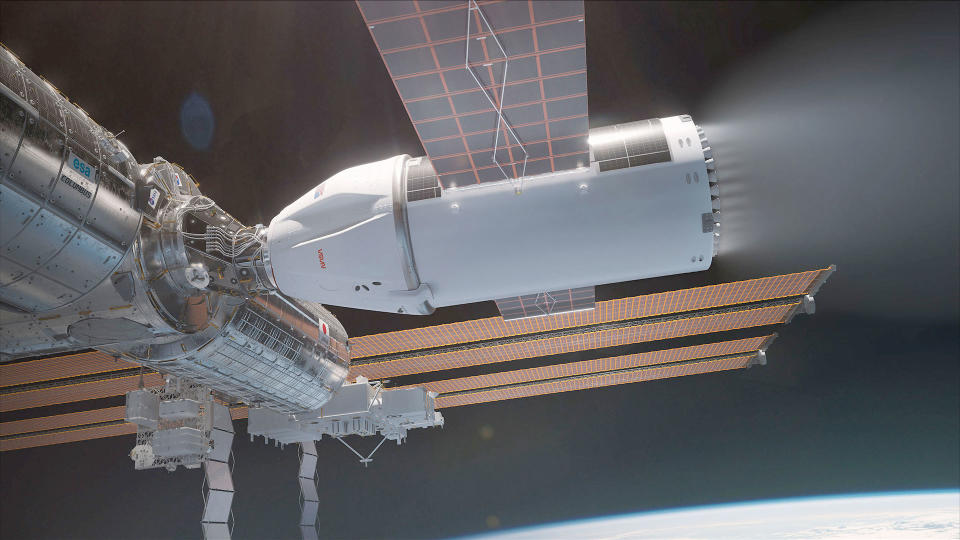

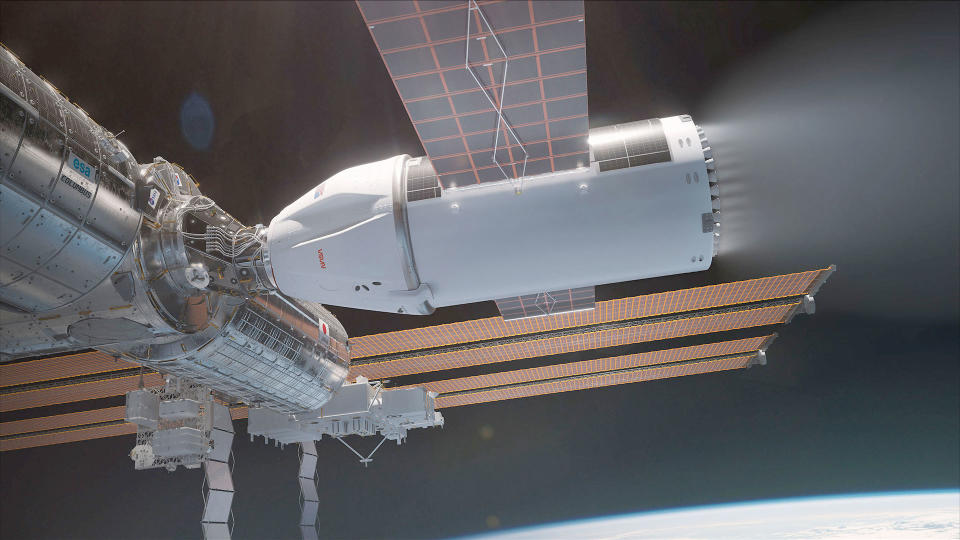

SpaceX has therefore designed a US Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) derived from Dragon. It is powered by 46 engines and will guide the space station through a controlled re-entry into the atmosphere.

Finding space for memories

As NASA concluded in a 2022 report, there is no way to return intact modules or truss segments to Earth for museum display.

“Unfortunately, we can’t take home really, really big things,” Bowersox said. “We’d love to take home big pieces, but the station wasn’t designed to be taken apart. It was designed to be put back together, and it would be relatively expensive to try to take home something really big.”

Contrary to the agency’s plans two years ago, NASA is now considering identifying smaller artifacts for preservation.

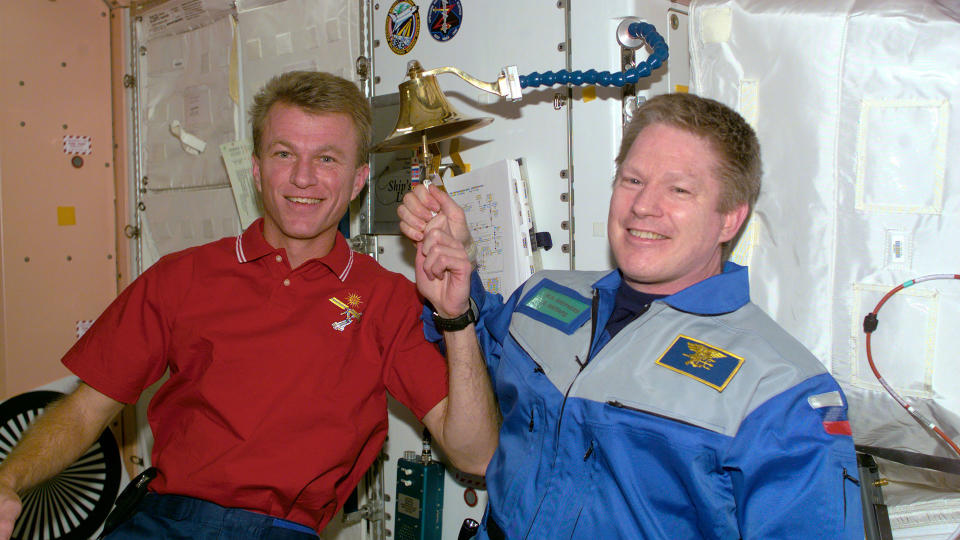

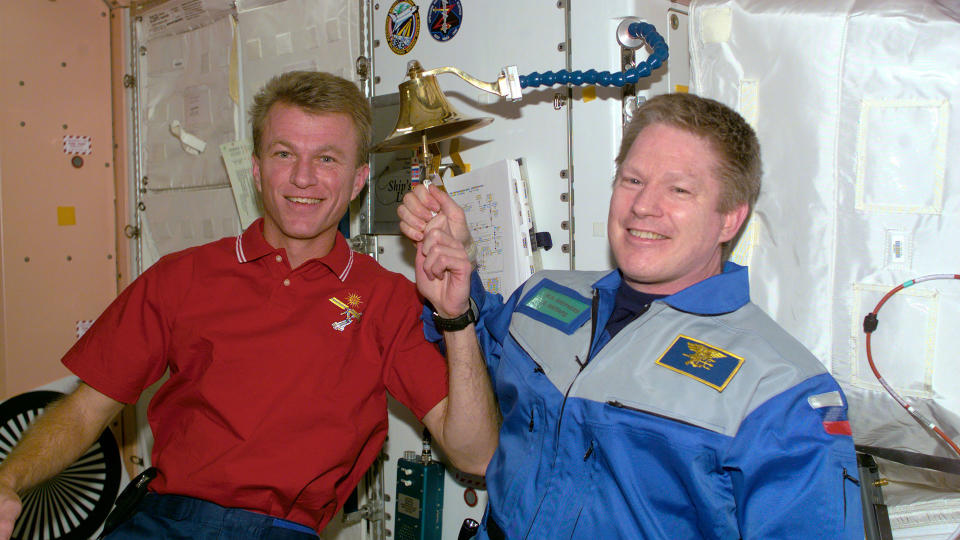

“I’m sure there is [are] “Some souvenirs that will come back and end up in museums someday,” Bowersox said. “For example, the ship’s bell, ship’s logs, maybe some panels with patches on them [and] “some, some exhibition items.”

According to a NASA white paper published last month, the agency is “in consultation with the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and other organizations to develop a plan for the preservation of a number of smaller objects from the space station.” But that plan does not include reserving the “downward mass,” or volume, on cargo vehicles that will bring the science results to the ground.

“We don’t really have enough disposable income for specific missions to bring hardware home,” said Dana Weigel, NASA’s manager for the International Space Station Program.

Weigel expects that space will open up as the need to return spare parts and used equipment for maintenance decreases.

“At the end of the life of the station, we don’t have a specific driver that brings items back to be refurbished. So it gives us more flexibility with what we take home,” she said. “It’s really work to decide, and we have plenty of time to do that, in terms of what we want to take home.”

Prioritizing conservation

NASA isn’t the only organization with hardware aboard the space station. The partners of the U.S. Operating Segment (USOS), including the European Space Agency (ESA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), have their own interests — as does Roscosmos, Russia’s federal space agency.

“Each partner on the USOS — ESA, JAXA and CSA — gets allocations for both up mass and return capability. And so each partner can work within their own allocation on what they want to do,” Weigel said, responding to a question from collectSPACE. “We don’t have a pre-negotiated agreement like we do with Roscosmos, because they have their own vehicle capabilities, so that’s much less likely because that’s not a normal part of the exchange and swap arrangements in the program.”

Decisions will also need to be made about potential artifacts that are working parts of the space station’s science and operational requirements. It remains to be worked out, for example, whether the CSA wants a part of its Candarm2 robotic arm or if the Smithsonian wants a part of a microgravity science glovebox, or whether it is appropriate to curtail research or maintenance activities in favor of preserving these items for posterity.

“I think everyone has something that’s important to them that they’d like to talk about and get down to the bottom line. The same goes for some of the prioritization between science activities or bringing back some of the conservation items,” Bowersox said. “The ISS program has a really good process for answering some of those questions, and as we get closer, we’ll have a list to go through to figure out what’s possible and how we can maximize the return for everyone who’s interested.”

To follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter via @collectSPACE. Copyright 2024 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.