Many of the companies promising “net-zero” emissions to protect the climate rely on vast forests and so-called carbon offsets to achieve that goal.

On paper, carbon offsets appear to offset a company’s carbon emissions: the company pays to protect trees, which absorb carbon dioxide from the air. The company can then claim the absorbed carbon dioxide as compensation that reduces the net impact on the climate.

However, our new satellite analysis reveals what researchers have suspected for years: forest offsets may not do much for the climate.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

When we looked at satellite tracking of carbon levels and logging activities in California’s forests, we found that carbon emissions are not increasing more in the state’s 37 offset project sites than in other areas, and that timber companies are not logging less than before. .

The findings send a pretty grim message about efforts to control climate change, and they add to a growing list of concerns about forest offsets. Studies have already shown that projects are often given too much credit in the beginning and may not last as long as expected. In this case, we run into a bigger problem: a lack of real climate benefits over the ten years of the program to date.

But we also see ways to solve the problem.

How forest carbon offsets work

Carbon offsets in forests work like this: trees capture carbon dioxide from the air and use it to build mass, effectively locking the carbon in the wood for the life of the tree.

In California, landowners can receive carbon credits for maintaining carbon stocks above a minimum required “baseline” level. Third-party verifiers assist landowners with the inventory by manually measuring a sample of the trees. To date, this process has only involved measuring carbon levels relative to baseline and has not taken advantage of the emerging satellite technologies we have been exploring.

Forest owners can then sell the carbon credits to private companies, with the idea that they have protected trees that would otherwise be cut down. This includes major oil and gas companies that use offsets to achieve up to 8% of state-mandated emissions reductions.

Forest offsets and other “natural climate solutions” have received a lot of attention from companies, governments and nonprofits, including at the UN Climate Conference in November 2022. California has one of the world’s largest carbon offset programs, with tens of millions of dollars flowing from it compensation projects and is often a model for other countries planning new compensation programs.

It is clear that offsets play a major and increasing role in climate policy, from individual to international levels. In our view, they should be supported by the best available science.

3 potential problems

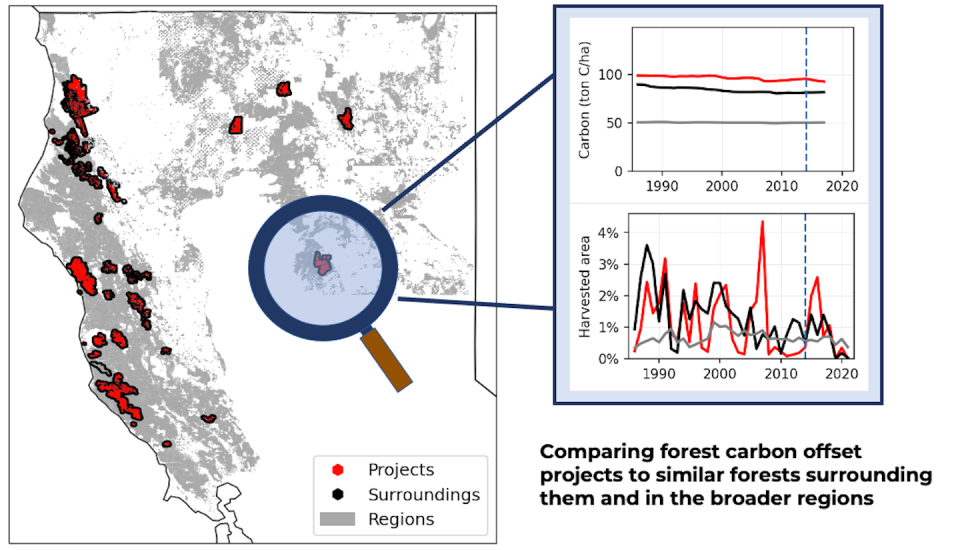

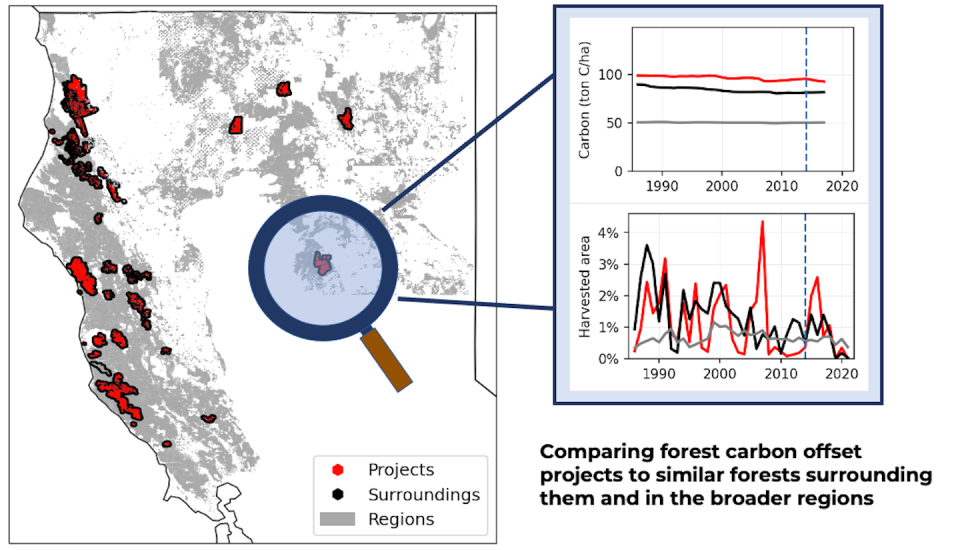

Our study used satellite data to track carbon levels, tree harvest rates and tree species in forest offset projects compared to other similar forests in California.

Satellites provide a more complete overview than on-site reports collected from offset projects. This allowed us to assess all of California since 1986.

From this broad view, we have identified three issues that point to a lack of climate benefit:

-

Carbon is not being added to these projects faster than before the projects began, or faster than in non-offset areas.

-

Many of the projects are owned and operated by large timber companies, which manage to meet offset credit requirements by keeping CO2 emissions above the minimum baseline level. However, these lands have been heavily harvested and continue to be harvested.

-

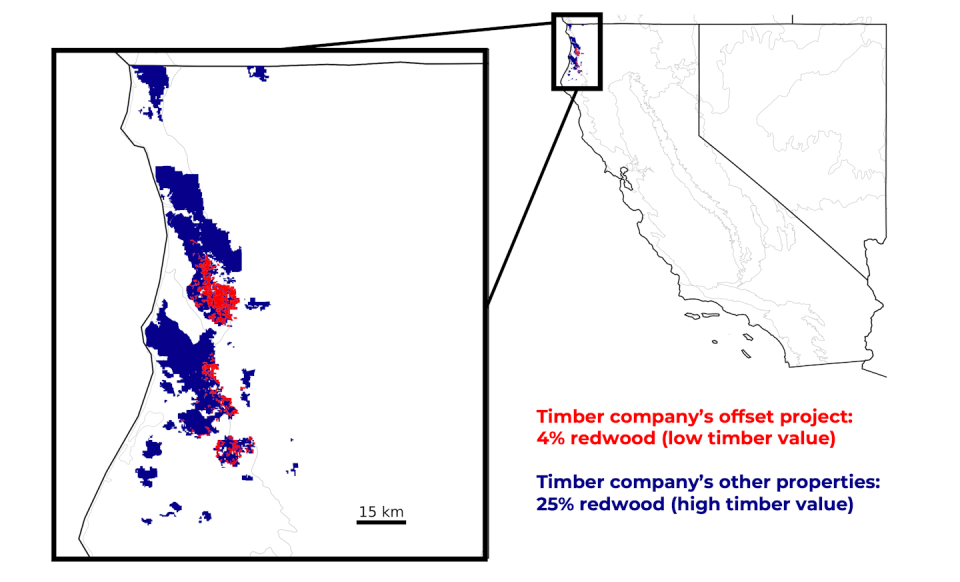

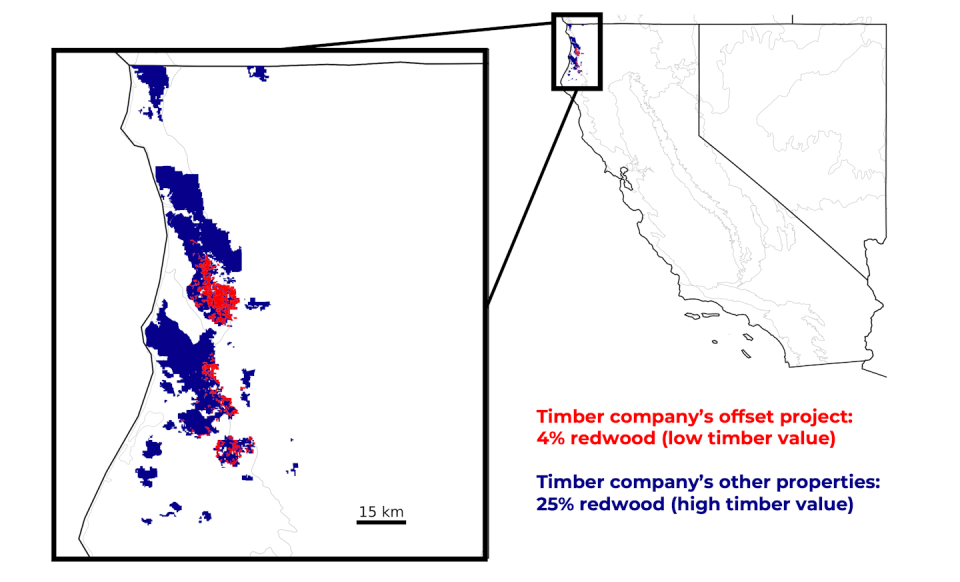

In some regions, projects are being implemented on lands with lower value tree species that are not at risk from logging. For example, at a large timber company in the redwood forests of Northwestern California, the offset project is only 4% redwood, compared to 25% redwood on the rest of the company’s property. Instead, the area of the compensation project is overgrown with tanoak, which is not salable timber and does not need to be protected from logging.

How California can fix its compensation program

Our research points to a series of recommendations for California to improve its compensation protocols.

One recommendation is to start using satellite data to monitor forests and confirm that they are indeed being managed to protect or store more carbon. For example, it could help foresters create more realistic baselines to compare offsets against. Publicly available satellite data is improving and can help make carbon offsets more transparent and reliable.

California can also avoid undertaking offset projects on lands that are already being conserved. We found several projects owned by conservation groups on land that already had low harvest rates.

Additionally, California could improve its offset contract protocols to ensure that landowners cannot opt out of an offset program and cut down those trees in the future. There is currently a fine for this, but this may not be high enough. Landowners may be able to start a project, receive a huge profit from the initial credits, cut down the trees within 20 to 30 years, pay back their credits plus penalty, and still come out ahead if inflation exceeds the obligation.

Ironically, while forest offsets are intended to help mitigate climate change, they are also vulnerable to it – especially in wildfire-prone California. Research shows that California vastly underestimates climate risks to forest offset projects in the state.

The state protocol requires that only 2% or 4% of carbon credits be set aside in a wildfire insurance pool, even though several projects have been damaged by recent fires. When forest fires occur, the lost carbon can be accounted for by the insurance pool. However, the pool may soon become depleted as the annual burned area increases in a warming climate. The insurance pool must be large enough to cover worsening droughts, forest fires, diseases and beetle infestations.

Given our findings around the challenges of carbon offsets in forests, focusing on other options, such as investing in solar energy and electrification projects in low-income urban areas, may yield more cost-effective, reliable and equitable results.

Without improvements to the current system, we may underestimate our net emissions, adding to the profits of large emitters and landowners and distracting from the real solutions of the transition to a clean energy economy.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Shane Coffield, NASA and James Randerson, University of California, Irvine

Read more:

Shane Coffield received funding from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program for his graduate studies at UC Irvine.

James Randerson receives funding from NASA, US Dept. of Energy Office of Science, the National Science Foundation, and the State of California Strategic Growth Council.