Glaciers in the Himalayas are melting rapidly, but a new report showed that an astonishing phenomenon in the world’s highest mountain range could help slow the impact of the global climate crisis.

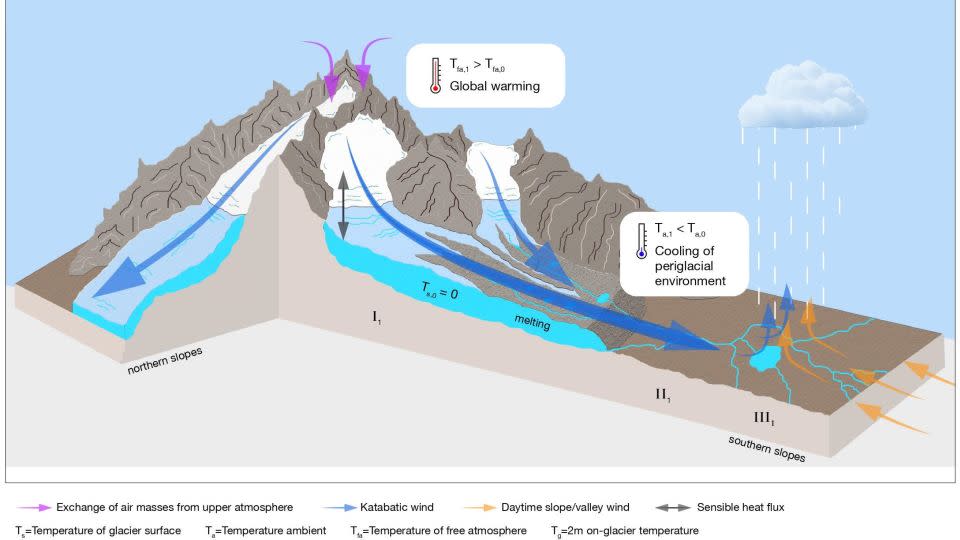

When warming temperatures hit certain high-altitude ice masses, it triggers a surprising response that blows robust cold winds down the slopes, according to the study published Dec. 4 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The warming climate is creating a greater temperature difference between the surrounding air above the Himalayan glaciers and the cooler air in direct contact with the surface of the ice mass, explains Francesca Pellicciotti, professor of glaciology at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria and lead author of the study. .

“This leads to an increase in turbulent heat exchange at the surface of the glacier and a stronger cooling of the air mass at the surface,” she said in a press release.

As the cool, dry surface air becomes cooler and denser, it sinks. The air mass flows down the slopes into the valleys and causes a cooling effect in the lower areas of the glaciers and adjacent ecosystems.

With ice and snow from the mountain range feeding 12 rivers that provide fresh water to nearly 2 billion people in 16 countries, it is important to find out whether Himalayan glaciers can maintain this self-sustaining cooling effect as the region experiences with a likely increase. of temperatures in the coming decades.

Glacier melts

A June report previously published by CNN found that glaciers in the Himalayas melted 65% faster in the 2010s compared to the previous decade, indicating that rising temperatures are already impacting the area.

“The main impact of rising temperatures on glaciers is an increase in ice loss due to increased melting,” said Fanny Brun, a research scientist at the Institut des Géosciences de l’Environnement in Grenoble, France. She was not involved in the investigation.

“The most important mechanisms are the extension and intensification of the melt season. They cause glaciers to thin and retreat, leading to deglaciated landscapes that tend to further increase air temperatures due to (by) greater energy absorption by the surface,” Brun said.

That energy absorption at the surface is determined by something called the albedo effect. Light or “white” surfaces such as clean snow and ice will reflect more sunlight (high albedo) compared to “dark” surfaces such as the land exposed as glaciers retreat, the soil and the oceans (low albedo). In general, Brun said this phenomenon is interpreted as a positive feedback loop, or a process that promotes change, but is generally poorly studied and difficult to quantify.

At the base of Mount Everest, however, readings of overall temperature averages seemed strangely stable rather than increasing. A close analysis of the data revealed what was really going on.

“While minimum temperatures have steadily increased, summer surface temperature maximums have continuously decreased,” said Franco Salerno, co-author of the report and researcher for the National Research Council of Italy, or CNR.

But even the presence of these cooling winds is not enough to completely counter the rising temperatures and melting of glaciers caused by climate change. Thomas Shaw, part of the ISTA research group with Pellicciotti, said the reason these glaciers are melting quickly is complex.

“The cooling is local, but may still not be sufficient to overcome the larger impact of climate warming and fully preserve the glaciers,” Shaw said.

Pellicciotti explained that the general scarcity of data in high altitude areas around the world led the research team to focus on using the unique ground observation data at one station in the Himalayas.

“The process we highlighted in the article is potentially of global importance and could take place on any glacier in the world where the conditions are met,” she said.

The new study provides compelling motivation to collect more long-term high-altitude data that is strongly needed to prove the new findings and their broader impact, Pellicciotti said.

Treasure trove of data

Located at a glacier elevation of 5,050 meters (16,568 feet), the Pyramid International Laboratory/Observatory climate station lies along the southern slopes of Mount Everest. The observatory has been recording detailed meteorological data for almost 30 years.

It’s those detailed meteorological observations that Pellicciotti, Salerno and a team of researchers used to conclude that warming temperatures are causing so-called katabatic winds.

The cold wind, caused by air flowing downhill, usually occurs in mountainous regions, including the Himalayas.

“Katabatic winds are a common feature of Himalayan glaciers and their valleys, and have probably always occurred,” Pellicciotti said. “What we are observing, however, is a significant increase in the intensity and duration of katabatic winds, and this is due to the fact that surrounding air temperatures have increased in a warming world.”

Another thing the team observed was higher ground-level ozone concentrations associated with lower temperatures. This evidence shows that katabatic winds act as a pump that can transport cold air from higher elevations and the atmospheric layers to the valley, Pellicciotti explained.

“According to current knowledge, Himalayan glaciers are doing slightly better than average glaciers in terms of mass losses,” Brun said.

Glacier loss in Asia versus Europe

Brun explained that glaciers in the central Himalayas have thinned an average of about 9 meters over the past 20 years.

“This is much lower than the glaciers in Europe, which have become thinner of about 20 meters (65.6 feet) in the same period, but this is greater than in other regions in Asia (for example in the Karakoram region) or in the Arctic,” Brun said.

Understanding how long these glaciers are able to locally counteract the effects of global warming could be critical to effectively addressing our changing world.

“We believe that katabatic winds are the response of healthy glaciers to rising global temperatures and that this phenomenon could help maintain permafrost and surrounding vegetation,” said co-author Nicolas Guyennon, a researcher at the National Research Council of Italy.

However, further analysis is needed. The research team then wants to identify the glacial features that promote the cooling effect. Pellicciotti said more long-term ground stations for testing this hypothesis are virtually lacking elsewhere.

“Even if the glaciers can’t preserve themselves forever, they can preserve the environment around them for a while,” she said. “We therefore call for more multidisciplinary research approaches to join efforts to explain the consequences of global warming.”

A separate 2019 report found that even in the most optimistic case, in which average global warming was limited to just 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures, the Himalayan region would experience at least a would lose a third of its glaciers.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com