A poorly understood virus spreading through South America has been linked to stillbirths and birth defects, raising fears of a repeat of the Zika outbreaks that ravaged the continent in 2015.

Brazil’s Ministry of Health sounded the alarm about the spread of Oropouche, reporting four cases of microcephaly — where a baby’s head is much smaller than expected — in newborns of mothers infected with the virus, as well as the death of a fetus.

The ministry has advised health workers to closely monitor infected pregnant women, amid warnings of an “impending crisis”.

“Pregnant women and their fetuses are once again at greater risk,” said Dr. Andre Siqueira, a researcher and infectious diseases expert at the Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas in Rio de Janeiro.

“It makes it even more worrying to think that not only were these most vulnerable individuals targeted for Zika, but that this could also be the case for Oropouche… We could be looking at a looming crisis,” he told the Telegraph.

In June, more cases of Oropouche were noted for the first time. Oropouche belongs to the arbovirus family, which also includes the Zika virus and dengue.

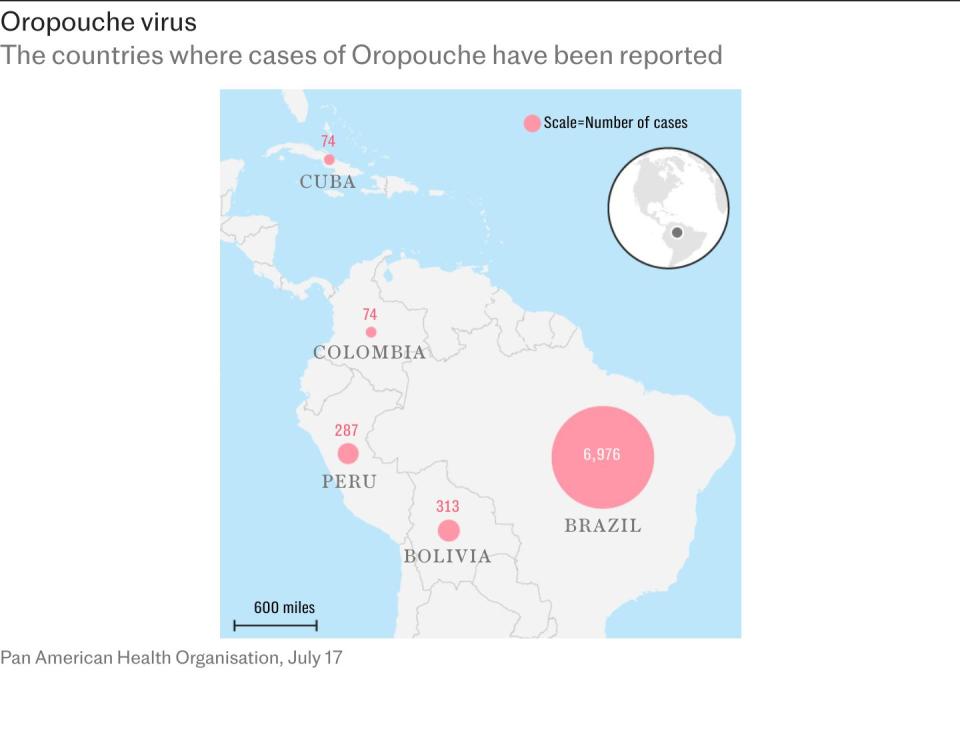

In Brazil, 6,976 cases have been confirmed this year, which is many times more than the number of infections recorded in the whole of 2023.

Cases have also been reported in Bolivia, Colombia, Peru and even across the ocean, in Cuba.

The virus is spread primarily by Culicoides paraensis, a small mosquito found in North and South America, and by the Aedes aegypti mosquito that feeds on infected three-toed sloths in the Amazon.

Scientists fear that Oropouche could develop into a major outbreak.

The cases reported by the Ministry of Health bear a striking resemblance to Zika infections.

Outbreaks of Zika in 2015 and 2016 led to more than 3,500 cases of infant microcephaly in Brazil, infecting an estimated 1.5 million people.

Scientists warn that, as in the early days of the Zika outbreak, the number of cases could be much higher than reported so far due to a lack of testing.

Since early 2024, Brazil has tested only 10 percent of samples from patients with symptoms of Oropouche fever who tested negative for Zika, chikungunya and dengue.

“Zika has been the big example so far. In terms of Oropouche… it’s kind of the great unknown at the moment,” said Dr Danny Altmann, professor of immunology at Imperial College London.

Mother-to-fetal transmission

In June, researchers from the Evandro Chagas Institute in Pará conducted a retrospective analysis of stored patient samples from cases of suspected viral infections causing neurological damage. These patients had previously tested negative for other arboviral diseases, including dengue, chikungunya, Zika and West Nile virus.

The analysis found that four babies born with microcephaly tested positive for antibodies to the Oropouche virus. These antibodies were found in both their blood and in the cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain and spinal cord. This suggests direct transmission from mother to fetus.

Earlier this month, the same institute identified and tested a fetus that was stillborn at 30 weeks of gestation and found genetic material from the Oropouche virus in the umbilical cord and multiple organs, including the brain, liver, kidneys, lungs, heart and spleen. Researchers are conducting further investigations and the link has yet to be confirmed.

“The more detailed clinical description, particularly of the outcomes, still needs to be done,” Dr. Siqueira said. “We still can’t establish a definite causal link with these observations, but it’s something that raises a red flag and concerns, given all the experiences with Zika, which could have a similar story.”

Dr Paul Hunter, professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia, said the link between the infection and foetal death “appears strong, but not definitive”, but that there was “certainly” transmission from mother to foetus.

Previous studies have shown that the Oropouche virus can enter the human brain and cause neurological problems. In severe cases, adults may experience encephalitis, dizziness and profound fatigue.

The strain behind the recent outbreak was first identified in the village of Oropouche, Trinidad and Tobago, in 1955. Five years later, a sloth carrying the virus was found during construction of the Belém-Brasília highway. Within a year, Oropouche fever began spreading to humans in the area, with about 30 reported outbreaks since then, all centered in the Amazon.

The current outbreak began in Roraima, northern Brazil, and has spread to the densely populated eastern coast, including Rio de Janeiro, Santa Catarina, Bahia and Minas Gerais. Only a few patients have traveled to the Amazon, suggesting local transmission of Oropouche. The remoteness of the suspected origin complicates the work of those investigating the outbreak.

“One of the problems in countries like Brazil, particularly the areas where these viruses occur, is that historically it can be quite difficult to access areas with affected populations because they are rural or remote,” said Professor Alain Kohl, professor of virology and infectious diseases at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Professor Altman explained that Oropouche is increasingly threatened by climate change, which is causing mosquitoes to fly further away. At the same time, increased rainfall and flooding are creating an ideal breeding ground for the insects.

Deforestation and urbanization can also lead to the displacement of host animals and mosquitoes and gnats feeding on humans rather than wildlife.

Dr. Siqueira warned that researchers must apply lessons learned from the Zika outbreak in the mid-2010s, when testing capacity was also limited and the severity underestimated.

The virus was first discovered in Uganda in 1947. Sporadic outbreaks occurred in the decades that followed, but in 2015 a major epidemic emerged in Brazil.

“Zika, when it first emerged in Brazil, was not considered a serious disease that would cause any concern – it had very mild symptoms. But now we know the consequences and the possibilities,” he said. “Now we need to push to find out earlier what the consequences might be … and try to use the lessons from the Zika emergency.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security