Hidden in the Cotswolds, on a potholed cul-de-sac, lies a quiet farming hamlet of six houses and a small church where a Norman arch gently turns inwards as the hillside slides imperceptibly downhill. The churchyard of St. Michael’s has no visible graves, apart from one unmarked mossy mound. This is the final resting place of Sonia Rolt (1919-2014). She lies next to her husband, Tom Rolt (1910-1974). Fifty years ago, Tom was the first person to be buried in this cemetery. Tom and Sonia had lived most of their married life in a beautiful house a minute’s walk away.

Tom Rolt was a prolific author, who wrote more than 40 books in less than 40 years, mainly at the desk of his family home in this Gloucestershire hamlet, Stanley Pontlarge, eight miles from Cheltenham. Lionel Thomas Caswall Rolt, to use his full name, was also an engineer and campaigner. His 1944 book Narrow boat, about his travels along the canals of England with his first wife Angela in a converted wooden freight boat, complete with bath, was a bestseller. Its success led to the formation of the Inland Waterways Association, which was responsible for saving canals from neglect and ushering in an era of leisure use.

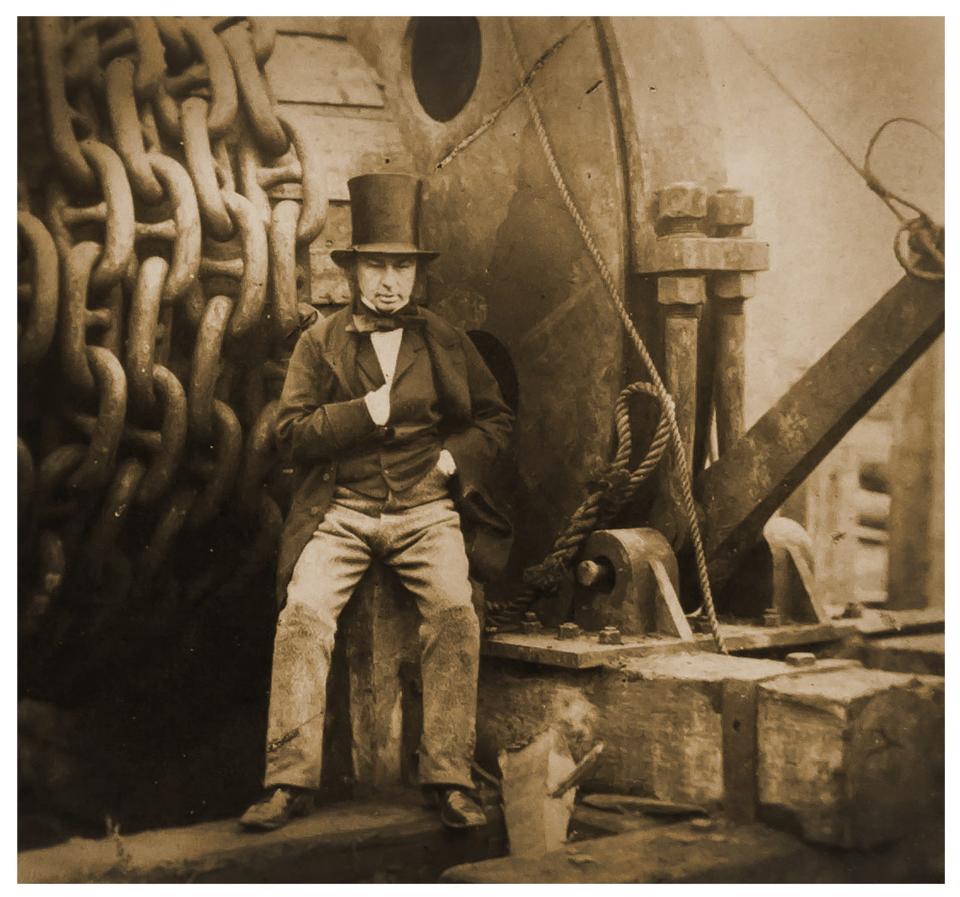

Previously, Tom’s first love was speed. He co-founded the Vintage Sports-Car Club and started the annual Prescott Hill Climb. He organised an Anglo-American vintage car rally (one of the vehicles travelling across Britain was a steam-powered car). He also wrote about railways and Victorian engineers – Brunel and Telford – and campaigned to keep the narrow-gauge Talyllyn railway in North Wales open. It is fitting then that since his death a railway line that runs a few yards past the Rolt family home – now a holiday home – has been restored as a heritage line.

The Gloucestershire Warwickshire Steam Railway clatters and roars through honey-coloured villages between Cheltenham and Broadway. Steam billows through the trees outside the cottage as I sit in the living room with Tim Rolt, Tom and Sonia’s youngest son, and he reminisces about how the house would shake as trains loaded with iron ore passed by. “The plates on the sideboard would all rattle,” he says, pointing to a display of pink willow crockery. “And sometimes tiles would slide off the roof into the street.”

When the line closed in the 1970s, Tim’s older brother, Richard, created a wheeled contraption powered by an old lawn mower and an airplane propeller, and the young men raced down the track at 20 miles per hour.

Nowadays, the crockery no longer rattles as trains pass, and the stone tiles remain firmly in place, but running out into the garden to wave at Pullman carriages pulled by a hissing steam locomotive is one of the bygone thrills of a stay at Stanley Pontlarge. The only other sounds are the bleating of rare breeds of sheep in the adjacent fields and the song of birds.

Inside, tiled and parquet floors, dark furniture, woodwork in earthy colours and shelves full of books create a relaxing, almost monastic atmosphere. I spent happy hours on the east-facing windowsill, reading and staring out the windows. Every now and then a horse and rider clattered past on the path, swifts flew high in the sky and in the golden evening a barn owl quartered the meadow.

“We have tried to maintain the atmosphere the house had when my parents lived here, but without the piles of paper and magazines everywhere, the boxes of which have been moved to Ironbridge Gorge Museum as part of an archive of my father’s work” , Tim says. “We want to keep my parents’ philosophy of not wasting things and keeping everything simple. We don’t want digital this or that.”

The three bedrooms share one bathroom, albeit an enormous one with a cast-iron claw-foot bath. The beds are firm, the furnishings understated, demonstrating Sonia’s good taste, who employed her to furnish The Landmark Trust’s properties when it started in 1965. The only concessions to the 21st century are Wi-Fi and a Smart TV, but almost every windowsill has a vase of fresh garden flowers and the shelves are packed with cloth-bound classics and poetry.

Upstairs, Tom’s desk still stands. Its shelves, once crammed with correspondence – perhaps from his friend, the poet John Betjeman, whom Tom liked to call Mr Stanley Pontlarge – are now a cabinet of curiosities, rescued by Tim and his partner Petra after Sonia’s death. There are opera glasses, model trains and a pipe.

“When Mum sent me to pick Dad up for dinner, his office was always a haze of blue smoke,” says Tim, who was paid sixpence to run to the letterbox with the day’s letters. Unfortunately, Tom’s typewriter has been temporarily lost, on loan to an exhibition somewhere.

If you’re more inclined to be outdoors, the back garden, where Tom would build model railways for the boys, is shaded by a horse chestnut and pear trees. A patchwork of flower borders is filled with herbaceous herb robert, daisies, foxgloves and long grasses; an English cottage garden growing delightfully wild. The house itself – two buildings, one 14th century, one 18th century – has a history that fills a chapter of Tom’s autobiography. On the south wall are traces of a small medieval sundial – or “mass dial” – and a newly carved inscription to Tom Rolt.

Through the wooden gate and past the chapel, a bridleway leads uphill through meadows of purple flowering grasses and orchids to a long-distance path, the Gloucestershire Way. With four friends I walked to Langley Hill and then to the village of Gretton, where we had Sunday lunch at The Royal Oak, while steam trains whistled past at the bottom of the garden and red kites wheeled high in the blue.

The day started with a church service. Apart from the fact that the minister apologized for us having to sing the hymns unaccompanied because he had forgotten his Bluetooth speaker, I imagined that the day would not be much different from the day that Tom and Sonia might have enjoyed – in a rare break between writing – in the 1950s. However, I have a feeling Tom would have rolled his eyes at the pastor’s announcement.

How to do that

The Cottage, which sleeps six, is available to rent from £217 per night. There is also a small bungalow on the property, built by Tom for his mother. Orchard Cottage sleeps two (plus two children in an adjoining bunk room). For more information about LTC Rolt and how to stay in his former home or Orchard Cottage, visit www.ltcrolt.org.uk. The first biography of Tom Rolt has just been published (May 2024) by Pen & Sword Books.