The HMS Terror, depicted here in an 1838 painting by William Henry Smyth, was trapped in pack ice west of Baffin Island and stranded on an ice floe for 118 days during a polar voyage, one of many casualties in the search for a way to escape the bypass route. the globe. (Royal Museums Greenwich)

The search for a Northwest Passage fundamentally shaped the history of Newfoundland, where John Cabot landed in 1497 while searching for a northwest sea route to Asia.

Although European sailors equipped themselves with the latest maritime technologies, from nimble caravels to magnetic compasses, their belief in the existence of a Northwest Passage was based on something far less modern: 1,800-year-old theoretical geography.

With only ancient philosophy and the Bible as evidence, Europeans were certain that a navigable, ice-free Northwest Passage must exist, and their quest to find it would ultimately take centuries and cost hundreds of lives.

A symmetrical world

When Europeans first ventured into uncharted waters, they had to rely on theory, rather than experience, to guide them.

Although the Vikings had reached the island of Newfoundland about 500 years earlier, detailed knowledge of this area beyond Greenland had not spread to other Europeans. Meanwhile, Marco Polo’s account of his travels through Asia had done little to clarify how those countries could be reached by sailing west from Europe.

With so little going on, would-be explorers relied on the most current guesses of what lay on the other side of the horizon. These predictions were based on sources that were, by our modern standards, far from scientific: ancient philosophy and Christian theology.

The eighth-century Mappa Mundi d’Albi shows a symmetrical idealization of the world as it was known to medieval Europeans. The map is centered on the Mediterranean Sea, with the Middle East at the top, Europe on the left and North Africa on the right. (Médiathèque d’Albi-Centre Pierre-Amalric)

One of the few ancient texts on geography to survive in Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire was Plato’s Timaeus.

According to the Timaeus, a divine creator designed our universe according to mathematical principles of balance and proportion. The very fact that the Earth is a sphere – ‘of all forms the most perfect’, ‘the form containing all other forms within itself’ – is proof of its physical flawlessness.

The Old Testament seemed to confirm Plato’s views. The Book of Isaiah describes creation as an act of precise calculation by a god who “weighed the mountains in a balance and the hills in a balance,” who “measured the waters in the hollow of his hand, measured the heavens with a span, and the dust of the earth in a certain measure.”

If the earth had been created in divine balance, according to medieval and Renaissance thinking, it was logical that the oceans and continents should be constructed symmetrically and in proportion to each other.

When 15th century explorers brought news of the Americas back to Europe, it confirmed what most geographers already believed: that the continent of Afro-Eurasia must have an equally sized counterpart on the other side of the globe.

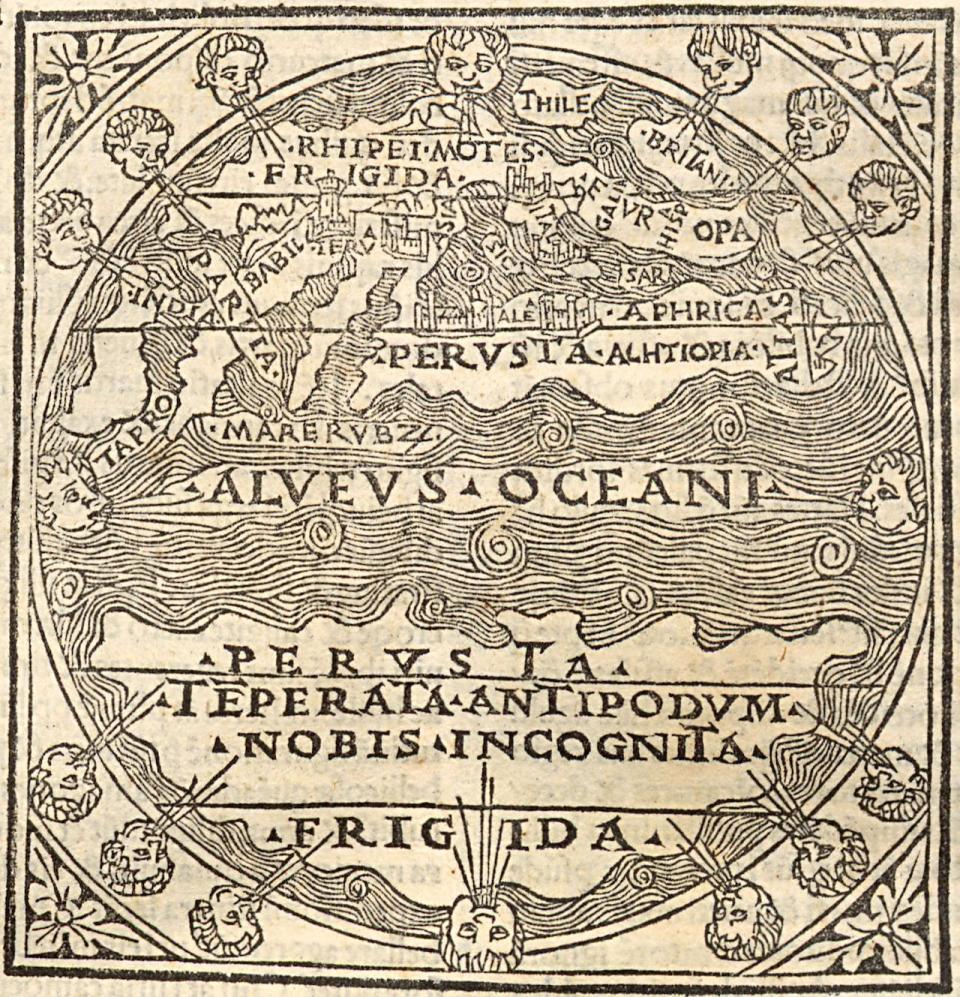

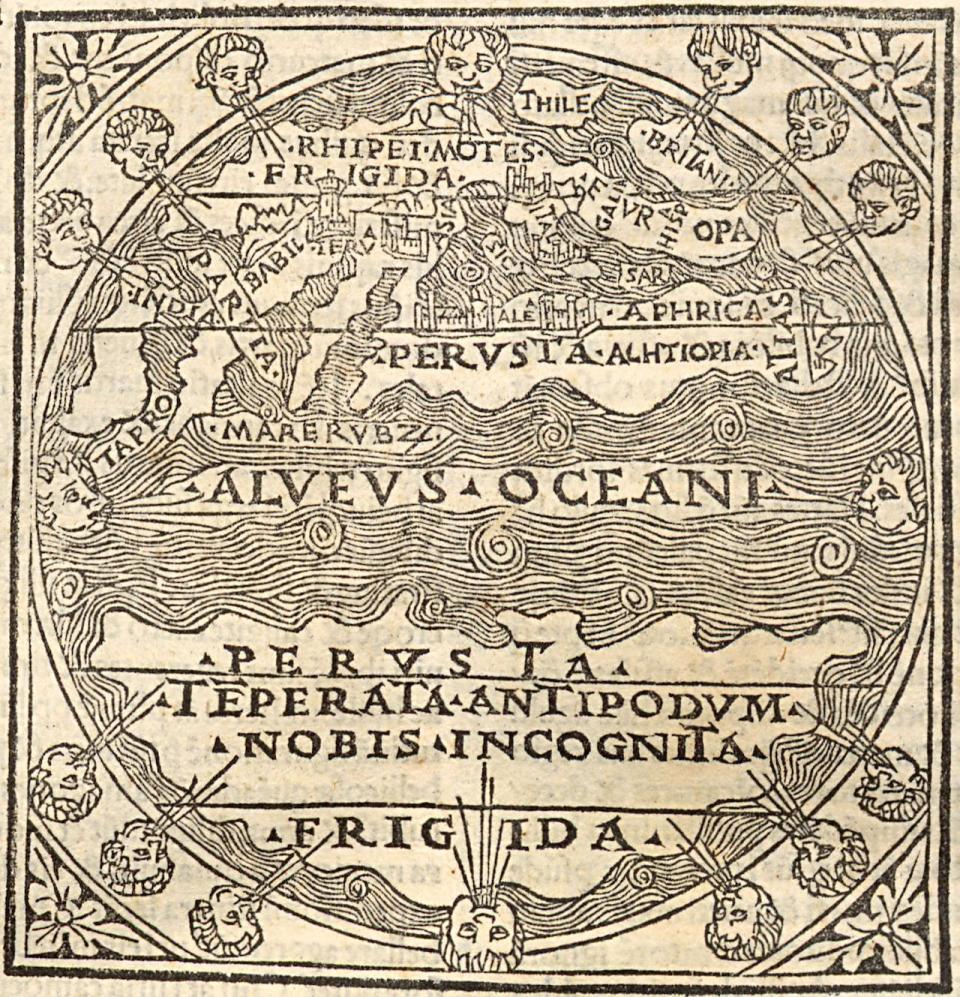

The top half of this 1489 world map, taken from a Venetian edition of Johannes van Eschenden’s Summa astrologiae legalis, shows Eurasia and Africa separated by the ocean current from a supposed southern continent of equal size. (Biblioteca Universidad de Sevilla.)

In 1487, Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope (the southernmost point of Africa) to reach the Indian Ocean, and in 1520, compatriot Ferdinand Magellan navigated a strait through the southernmost tip of South America to the Pacific Ocean.

According to the prevailing theory of symmetrical geography, these voyages proved the existence of southwestern and northeastern passages. If there were open sea routes to the south of the world’s continents, there must also be open sea routes to the north.

The wizard who trained the explorers of England

English explorers of the sixteenth century received thorough training in the principles of theoretical geography before setting out, given by none other than the famous occultist John Dee.

As an advisor to Elizabeth I, Dee’s astrological predictions, angelic communications, and mystical writings earned him the nickname “the Queen’s Magician,” and he tutored the leaders of every English expedition to northern waters in the second half of the sixteenth century. century, including Martin. Frobisher, Humphrey Gilbert and John Davis.

Steeped in ancient philosophy and Christian Kabbalism, he taught them the theory of symmetrical geography and used philosophical reasoning to justify the search for a Northwest Passage.

John Dee conducts an experiment for the English court in an oil painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni. (Wellcome Collection)

As strange as it may seem that a wizard had so much influence on English exploration, Dee’s influence demonstrates the thin line between magic and science at the time. While he may have been fascinated by mysticism, Dee was above all a mathematician.

He used his mathematical talent not only to draw horoscopes and practice numerology, but also to make astronomical observations, study Euclidean geometry and develop new navigation instruments.

What we now consider the natural sciences was classified as ‘natural philosophy’ from the fourth century BC until the 19th century and considered a branch of philosophy broadly defined, just one way of trying to better understand the world through observation and research. rode.

The theory of a symmetrical Earth continued to drive exploration of the Canadian Arctic until Franklin’s doomed expedition of 1845-1848. His two ships, the Terror and the Erebuswere trapped in impenetrable ice for three years, leading to the death of all 129 crew members from scurvy, starvation and exposure.

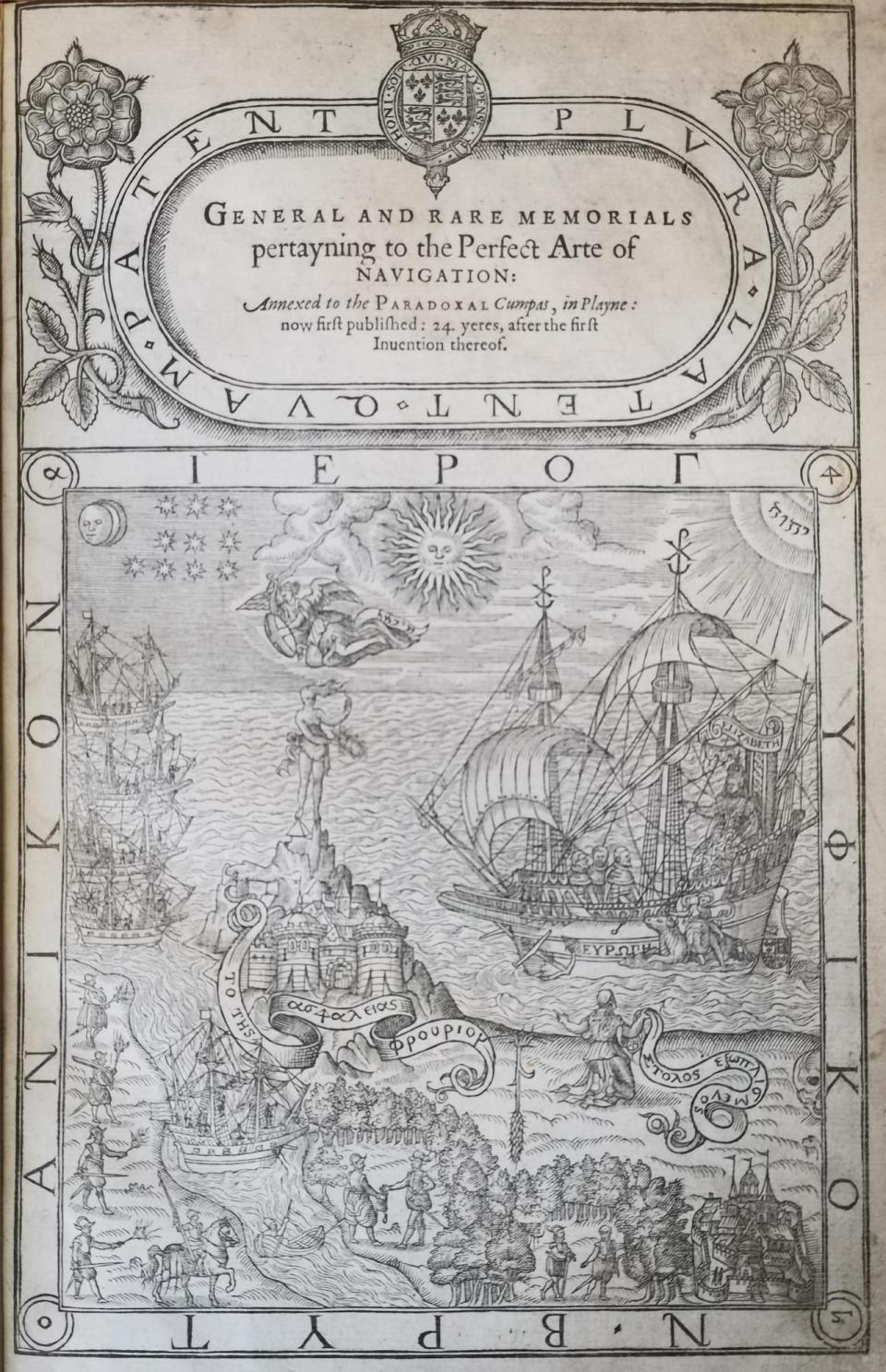

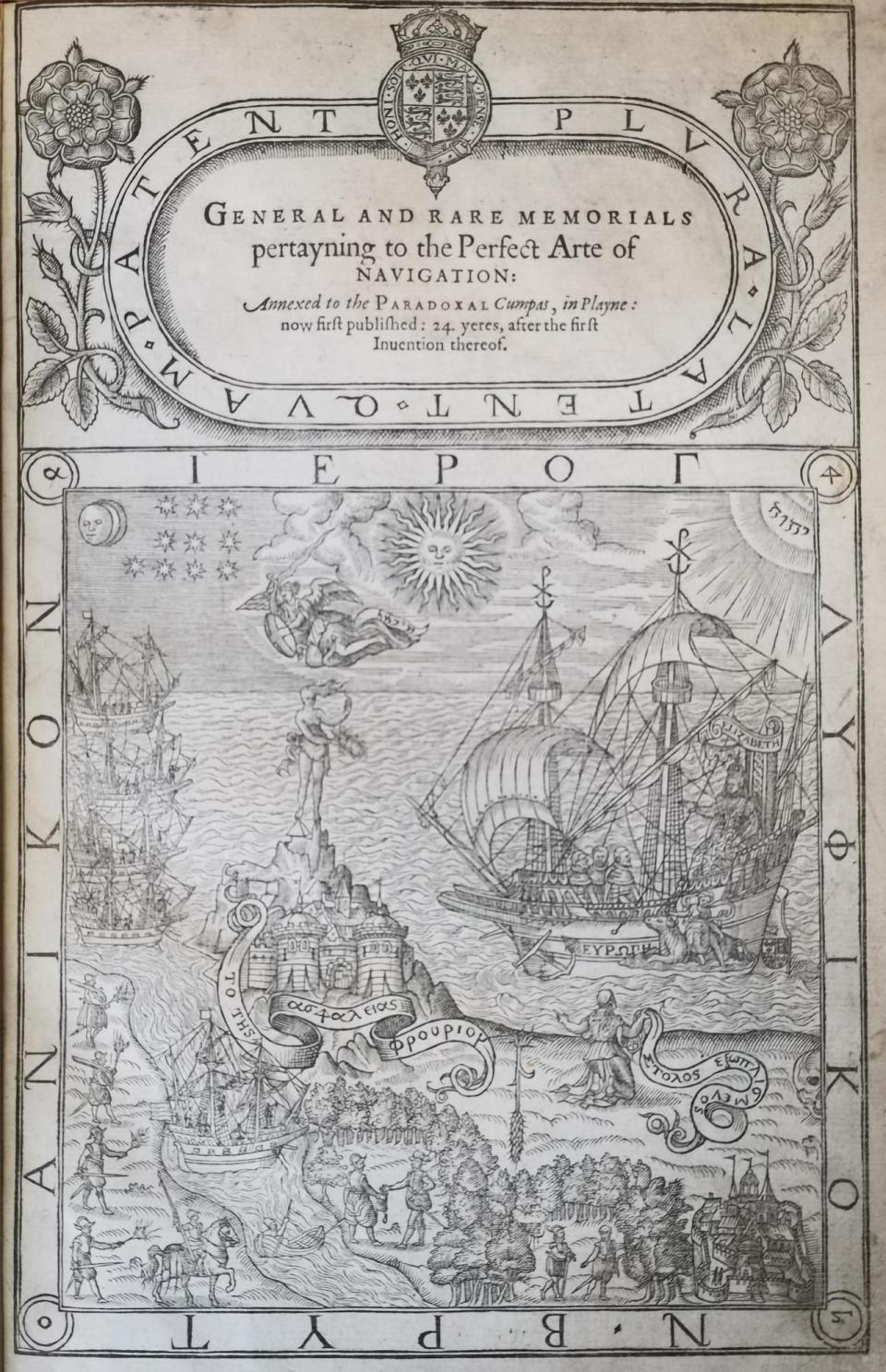

The title page of John Dee’s 1577 book on the art of navigation contains esoteric symbols, including the sun, moon, stars and a glowing tetragrammaton, to symbolize the divine approval of British imperialism under Queen Elizabeth I. (Royal Museums Greenwich)

Ultimately, the Northwest Passage was only discovered by chance in 1853 by Richard McClure and the crew of HMS researcherwho were searching for Franklin’s lost expedition.

They sailed through the Strait of Magellan in South America to the Pacific Ocean and entered the Arctic Ocean from the west. Then, when the Researcher became entangled in pack ice and were forced to abandon it. They continued their way east by sledge and were themselves rescued by another British ship.

This second rescue ship also eventually had to be abandoned after being trapped in the ice, and everyone on board was forced to hike south to safety.

Although they had found the legendary Northwest Passage, they had refuted the theory of symmetrical geography, as the Northwest Passage, unlike its counterpart to the south, was not found to be reliably ice-free.

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push notifications for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.