Dangerous territory, death taxes – new Finance Minister Rachel Reeves is about to find out whether, in her quest for more taxpayers’ money, she decides to enter this political minefield.

“The art of taxation,” declared Jean-Baptiste Colbert, finance minister under Louis XIV, “consists in plucking the goose so as to obtain as many feathers as possible with as little hissing as possible.”

No matter how Reeves does it, fiddling with the inheritance tax is guaranteed to elicit a particularly loud outburst of hiss. Yet it’s also one of the sources of government revenue the new Chancellor doesn’t want to tie her hands to, making it a firm favorite to pick.

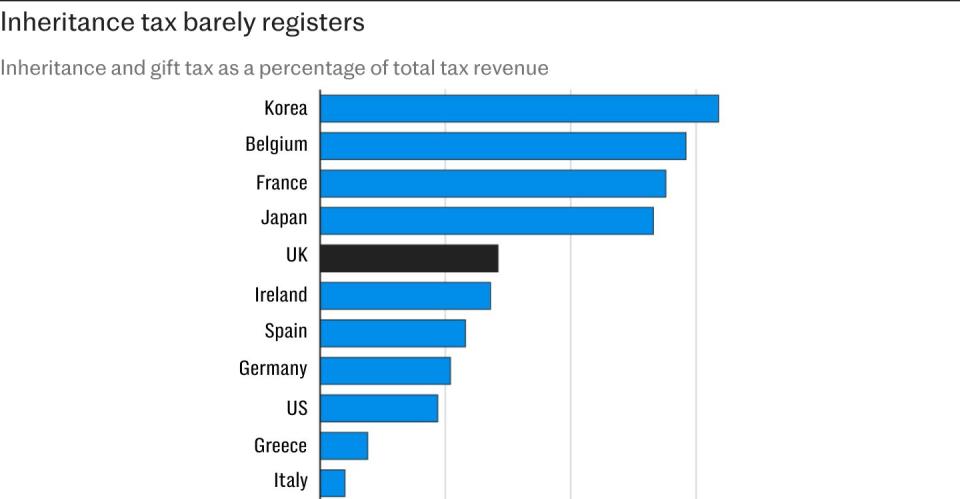

Right on schedule, the left-wing think tank Demos has released a 65-page report on inheritance tax reform, which helpfully points out that all but one of the G7 economies generate significantly more inheritance tax revenue than we do in the UK.

One exception to this is Italy, where the tax rate is extremely low and only applies to estates over €1 million (£840,000).

Everyone else, including the US, manages to outdo the UK, where just 4.2% of wealth passed on in tax in the 2019/20 tax year was paid. At just 0.7% of government revenue, inheritance tax barely registers.

The temptation for Reeves must be irresistible. If we were to adopt the same system as South Korea, for example, the Treasury could raise £6.5bn more a year in inheritance tax than it does now, Demos says, and a further £2.5bn if we adopted the same approach to lifetime wealth transfers.

Reform is all the more tempting because inheritance tax as it stands is widely seen as unfair. For the very wealthy it is almost entirely avoidable, but for Middle England, which is increasingly being hit by the tax because of rising house prices, it is almost impossible to avoid.

But just because it is seen as unfair does not mean it is easy to reform. There are good reasons for the exemptions for transferred holdings and farmed agricultural land, for example, and not just because family businesses and farms are enterprises you want to encourage.

Much of the German economy is built around its mittelstand of small and medium-sized family businesses that are passed down from generation to generation. If only we had something similar here in the UK.

Imposing inheritance taxes on such enterprises could threaten them with break-up or otherwise make them commercially unviable. The same applies to farms, which could become uneconomic if they were forced to sell land to pay inheritance taxes.

Some farmers have already been trapped by government-sponsored rewilding programs, but now it turns out that rewilded land is no longer exempt from inheritance tax.

The point about inheritance taxes, however, is that they offend something deep in the human psyche: the desire to collect the fruits of one’s labor or good fortune and pass them on to descendants or chosen causes.

It’s in our DNA and no amount of political moralizing or social engineering can drive it out. Death taxes are a tax on aspirations, pure and simple. They are also a form of double taxation, because they are levied on money that has already been taxed in most cases.

Oddly enough, you might think, it is one of those taxes that many people feel they have to pay, even though a relatively small proportion of estates do. Raising the level at which the tax is payable is therefore politically popular, even though few enjoy the benefit.

Conversely, Reeves would undoubtedly lose votes if he tried to lower the threshold; many more people would think they had been held liable than they actually were.

Ken Clarke, former Chancellor of the Exchequer, once said that he gave up on tax reform when he realised that no matter what he did, there would be winners and losers. Politically, he would be punished by the losers, while the winners would give him no credit at all.

Reeves may learn this lesson the hard way about inheritance tax. Despite fiscal pressure to raise taxes, she would do well to proceed with caution.

There is no doubt that the UK system as it is currently constructed is an extremely bad tax. As Chris Sanger, EY’s head of tax policy, puts it: “If you were designing the system from scratch, you wouldn’t be starting here.”

The simplest solution would be to abolish the tax altogether, which was ultimately the intention of the previous Tory government. But that is clearly not going to happen under Labour.

There are jurisdictions, such as Singapore, where the tax has never been levied. But outside tax havens like this booming city-state, it is hard to find an economy without some form of inheritance tax.

It is true that in Canada, Australia and Norway there is no inheritance tax as such, but in all three jurisdictions recipients of passed-on assets are instead held liable for capital gains increases, either upon inheriting an estate or upon selling the assets. These can reasonably be seen as the same thing.

It is also true that in most OECD countries the tax is levied on income rather than on the estate. This has always seemed to me to be a structurally better approach. What all these systems have in common, however, is that they are incredibly complicated, subject to peculiar quirks and are generally seen as unfair.

Some are more progressive than others, however. Labour’s redistributionist aims will undoubtedly also influence the overhaul of the UK system. The government could also combine this with some form of continued wealth tax.

If Reeves were truly radical, she could even replace the inheritance tax with a lifetime wealth tax.

Whatever she does, she must first understand that all wealth taxes often have quite damaging behavioral consequences. Surprise – they are generally not at all conducive to wealth creation, growth, and thus ultimately to expanding the tax base.

We are already seeing some of these consequences in the proposed abolition of tax breaks for non-doms. Many non-doms are voting with their feet. The same will happen with inheritance tax. If you push too hard on wealth, it will simply go somewhere else.

In today’s world, capital is highly mobile; plucking feathers with a minimum of hissing was hard enough in Colbert’s day. It’s harder still today.