On the morning of December 6, 1917, a French freighter named SS Mont-Blanc collided with a Norwegian ship in Halifax Harbor in Nova Scotia, Canada. The SS Mont-Blanc, loaded with 3,000 tons of explosives intended for the battlefields of the First World War, caught fire and exploded.

The resulting explosion released an amount of energy equivalent to approximately 2.9 kilotons of TNT, destroying much of the city. Although it was far from the front lines, this explosion left a lasting impression on Halifax, in the way that many regions experience environmental change due to war.

Media attention is often drawn to the destructive explosions caused by bombs, drones or missiles. And the destruction we have witnessed in cities like Aleppo, Mosul, Mariupol and now Gaza certainly serve as stark reminders of the horrific consequences of military action.

However, research is increasingly revealing broader and longer-term consequences of war that extend far beyond the battlefield. Armed conflicts leave a lasting trail of environmental damage, posing challenges for recovery after hostilities subside.

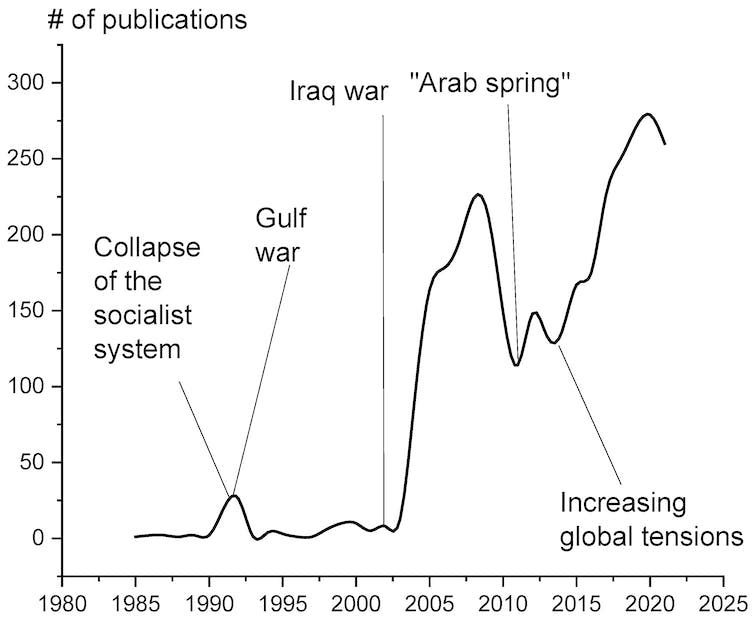

Research interest in the environmental effects of war

Toxic legacies

Battles and even wars are over relatively quickly, at least compared to the time scales on which environments change. But soils and sediments record their effects over decades and centuries.

In 2022, a study of soil chemistry in northern France showed elevated levels of copper and lead (both toxic at concentrations above trace levels) and other changes in soil structure and composition, more than 100 years after the site was part of the Battle of the Somme.

Research into more recent conflicts has also revealed the toxic legacy of intense fighting. A study conducted in 2016, three decades after the Iran-Iraq war, found concentrations of toxic elements such as chromium, lead and the semi-metal antimony in battlefield soils. These concentrations were more than ten times higher than those in the soil behind the front lines.

The deliberate destruction of infrastructure during war can also have lasting consequences. A notable example is the first Gulf War in 1991, when Iraqi forces blew up more than 700 oil wells in Kuwait. Crude oil flowed into the area, while fallout from scattered smoke plumes created a thick deposit known as ‘tarcrete’ across 1,000 square kilometers of Kuwait’s deserts.

The impact of the oil fires on air, soil, water and habitats attracted worldwide attention. Now, in the 21st century, wars are closely monitored in almost real time for the damage done to the environment and the harm done to people.

Conflict is a systemic catastrophe

One result of this research is the realization that conflict is a catastrophe that affects entire human and ecological systems. Destruction of social and economic infrastructure such as water and sanitation, industrial systems, agricultural supply chains and data networks can lead to subtle but devastating indirect impacts on the environment.

Since 2011, conflict has marred Syria’s northwestern regions. As part of a research project led by my Syrian colleagues at Sham University, we conducted soil surveys in the affected areas.

Our findings revealed widespread diffuse soil contamination in agricultural land. This country feeds a population of approximately 3 million people who already face severe food insecurity.

The pollution is likely the result of a combination of factors, all of which are the result of the regional economic collapse caused by the conflict. A lack of fuel to pump wells, combined with the destruction of wastewater treatment infrastructure, has led to increased reliance on streams contaminated with untreated wastewater to irrigate croplands.

Pollution can also arise from the use of low-quality fertilizers, unregulated industrial emissions and the proliferation of makeshift oil refineries.

More recently, the current conflict in Ukraine, which prompted international sanctions against Russian grain and fertilizer exports, has disrupted agricultural economies worldwide. This has hit countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Nigeria and Iran particularly hard.

Many smallholder farmers in these countries may be forced to sell their livestock and give up their land as they struggle to purchase the materials they need to feed their animals or grow crops. Land abandonment is an ecologically damaging practice because it can take decades to restore the vegetation density and species diversity typical of undisturbed ecosystems.

Warfare clearly has the potential to become a complex and intertwined ‘nexus’ problem, the consequences of which are felt far beyond war-affected regions.

Conflict, cascades and climate

Recognizing the complex, cascading consequences of war on the environment is the first step in addressing them. After the first Gulf War, the UN established a compensation commission and identified the environment as one of six compensable damages caused to countries and their people.

Jordan was awarded more than $160 million over ten years to restore the vast areas of the Badia Desert. These vast areas had been ecologically devastated by a million refugees and their livestock from Kuwait and Iraq. The Badia is now a case study in sustainable watershed management in arid areas.

Work is underway in Syria’s northwestern region to assess farmers’ understanding of soil contamination in conflict-affected areas. This marks the first step in designing agricultural techniques aimed at minimizing threats to human health and restoring the environment.

Armed conflicts have finally made their way onto the climate agenda. The latest UN climate summit, COP28, includes the first theme day dedicated to “relief, recovery and peace”. The discussion will focus on countries and communities where the ability to cope with climate change is hampered by economic or political vulnerability and conflict.

And as COP28 kicked off, the Conflict and Environment Observatory, a British charity that monitors the environmental impact of armed conflict, called for research into carbon emissions in conflict-affected regions.

The carbon impact of war is still not included in the global inventory of carbon emissions – a vital reference point for climate action. But far from the sound and fury of the explosions, the environmental consequences of warfare are persistent, ubiquitous and equally deadly.

Don’t have time to read as much about climate change as you’d like?

Instead, get a weekly digest in your inbox. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environmental editor writes Imagine, a short email that delves a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join over 20,000 readers who have subscribed so far.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jon Bridge volunteers with the Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara) to support their Syria program, which funded some of the work described in this article.