It is not the first time that Taylor Swift has caused her fans to go into an uproar. It was last June and the world’s biggest pop star had just announced the European dates of her blockbuster Eras tour, leaving an obvious Glastonbury-sized hole in the schedule.

Feverish speculation arose that Swift — who had originally agreed to headline the Pyramid stage in 2020 before the pandemic hit — would make her late bow at Worthy Farm. Glastonbury organizer Emily Eavis said in 2022 that “I think we’ll have Taylor on board the next time she goes on tour”.

But after weeks of hope, the hammer blow came. Instead, Swift, 34, will play Dublin’s Aviva Stadium for each of the festival’s three nights as her massive tour continues. Glastonbury partygoers will have to make do with Dua Lipa, Coldplay (for a record-breaking fifth time) and US RnB star SZA.

Swift is unusual, as the 34-year-old’s tour is the first in history to gross more than $1 billion (£790 million) in ticket sales, but her departure from Glastonbury illustrates an important point. The festival simply doesn’t pay its headliners and other acts particularly well, and Swift is too big now to need that honor.

Lipa is clearly headliner material: a homegrown global superstar who is reaching her peak with a new album. But Coldplay feels, even to their defenders, like a safe bet, while SZA, despite her Grammy and Brit awards, wasn’t the first choice. Madonna, fresh off the success of her Celebration tour, was said to be lining up for the Sunday before arguments over money put an end to those discussions. After last year’s all-male trio of headliners in the form of Arctic Monkeys, Guns N’ Roses and Elton John, Glastonbury’s string of leading acts was disappointing.

Glastonbury is a unique festival due to its relative lack of corporate sponsorship, its commitment to donating millions of pounds to charities every year and the general attention given to it by the BBC. Last year’s festival, which brought 140,000 visitors to Worthy Farm, cost £62 million to put on and Glastonbury made a record £3.7 million in charity donations.

While many festivals have big-budget sponsors, BST in Hyde Park is sponsored by American Express. Glastonbury eschews such revenue by giving up prime advertising space to the charities Oxfam, Water Aid and Greenpeace.

The result is that Glastonbury, by its own admission, pays far less than other festivals – just 10 per cent of the more than £1 million in fees artists can earn. “We’re not in a situation where we can just give people huge amounts of money,” Eavis said in 2017. “So we’re very grateful for the bands that we get, because they’re basically doing it for the love of it.”

When the Rolling Stones played their bravura 2013 headline set, they built a huge catwalk into the audience so a dancing Mick Jagger could stand closer to spectators and they had a mechanical phoenix that came to life during Sympathy for the Devil. As a result, the band spent more money putting on the show than they were paid for it. In the run-up to that year’s festival, founder Sir Michael Eavis admitted that they were not paid more than other headliners, despite being able to charge millions for other one-off shows.

“There is a standard price for the headliner. We get the headliners for a tenth of the normal price. So they don’t get paid much,” he said. Sir Paul McCartney was paid just £200,000 for his 2022 headline slot, when he normally receives more than £2.5 million.

So why do artists still play Glastonbury when other festivals and stadium tours are more lucrative? Partly because Glastonbury sets live long in the memory and can be career defining, combined with the extent of Wimbledon coverage on the BBC. Eavis also said in 2013: “Headliners are always good for us, because they want to do it, because they get TV and they get huge record sales right after the show.”

The organizer of a rival festival sees it differently. “Glastonbury is a big TV show and the BBC pays for it. I resent that because I pay the licensing fees, so I pay for Glastonbury and they pay 10 percent of what I have to pay to artists,” they say. “They pay a lot less than other festivals because of the BBC coverage.”

The Corporation is notoriously tight-lipped about how many millions of pounds it is using to secure exclusive broadcast rights for the festival, as well as the cost of sending hundreds of staff to Somerset. Historically, it has used exceptions in the Freedom of Information Act to protect journalism and free speech to avoid answering the questions of license fee payers.

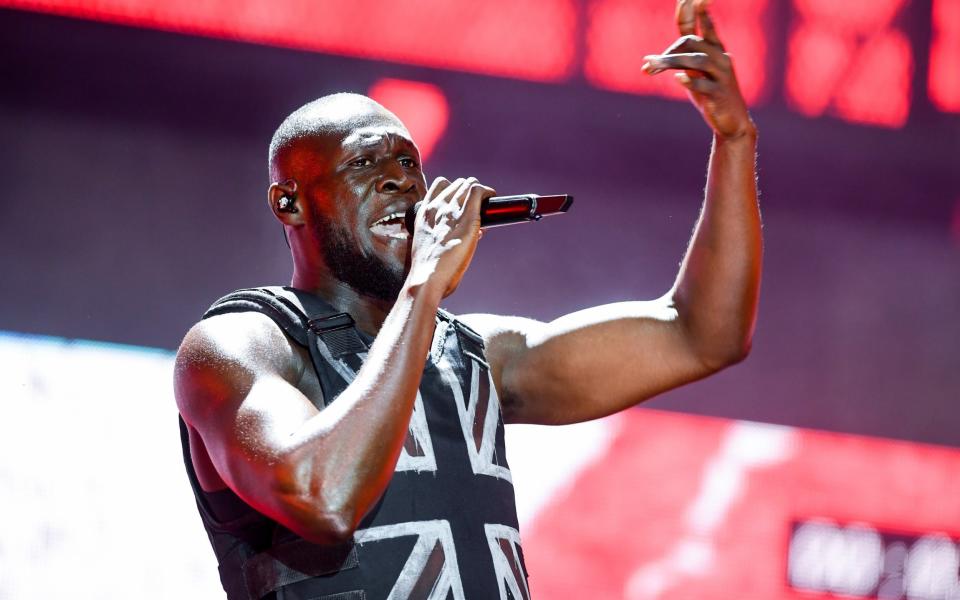

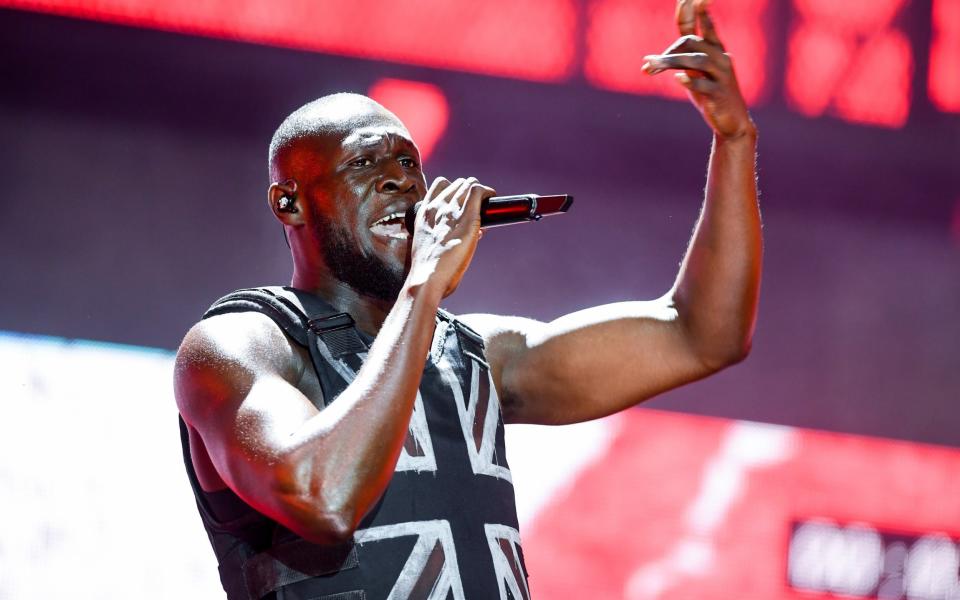

For an artist like Stormzy, who headlined the Pyramid Stage in 2019 with a show said to have cost more to put on than any previous set, it marked the rapper’s definitive move from the grime world to the mainstream . In the week after Stormzy’s set, in which he wore a Banksy-designed Union Jack stab-resistant vest, sales of his album Gang Signs and Prayer soared by more than 300 percent, jumping up the charts from 73rd to 14th. That same year, Kylie Minogue, who was in the “legend” slot on Sunday afternoon, released a greatest hits album to coincide with Glastonbury. It went straight to number one.

Alan Edwards, the acclaimed PR svengali, writes in his new book how he got David Bowie to play a set on the Pyramid stage in 2000, reviving his flagging career. The set went down in history: Bowie played for 250,000 people, even though the fee was meager. “It was hilarious, it cost like £20,000 or something, and even then it wasn’t a lot of money,” says Edwards. “David was always an artist and he was driven by what he thought was the right thing and what he wanted to do, rather than what the payday was. He didn’t even ask. It was cool to do. Glastonbury has that wonderful legacy.”

In addition to the absence of Swift and Madonna from the lineup, there are signs that some artists won’t tolerate the lower fees. Nadine Shah, who is a vocal supporter of fair pay for singers, said she turned down a place at Worthy Farm this year. “I would have liked to, but I wasn’t offered a television stage, so I declined,” she said. “It’s too expensive a blow for me to take otherwise.”

John Giddings, the agent and promoter of the Isle of Wight Festival, says he has discussed the (relative) lack of money at Glastonbury with the organisers. “Michael Eavis once asked me how I booked Fleetwood Mac, even though he had been trying them for years,” says Giddings. “I said, ‘Michael, I paid them’.” It’s telling that, despite early speculation that she might finally play the Sunday afternoon “legend” slot at Glastonbury, Stevie Nicks is one of the headliners for BST this year.

Mick Fleetwood said in 2019: “I will burn in hell if we don’t do that [Glastonbury] ever,” but Nicks himself said this month that, following the untimely death of Christine McVie in November 2022, there is now “no chance of putting Fleetwood Mac back together in any way.”

In a sense, none of this matters. Glastonbury’s £355 tickets sell out many months before any acts are confirmed in the line-up, so Emily Eavis can almost do whatever she wants. Much of her focus in recent years has been on supporting a new generation of artists, especially women, who have long been underrepresented as festival headliners. In addition to the big performances at this year’s festival, performances include Fontaines DC, The Last Dinner Party and Little Simz. They all have prominent slots and are almost guaranteed an audience of tens of thousands each.

“We are doing our best, so the pipeline needs to be developed,” Eavis said last year. “This starts a long time ago with the record companies and radio. I can shout as loud as I want, but we have to get everyone on board.”