Whenever I think about Moldova (which is not often, to be honest), I am reminded of a post from a photographer friend when he visited here a few years ago: “Less than a minute after crossing into Moldova, I witnessed three horses and carts, and a goat on a rope. My phone informed me that I was in a ‘Zone D’ destination worldwide, it felt like Zone Z.”

And that’s it in a nutshell: Moldova feels like Zone Z. The last place on earth you would go to. And if that’s your perception of this small Eastern European country, tucked behind Romania, lost like a silver penny among the geopolitical cushions of Eurasia, then you’re not alone: statistics show that Moldova gets fewer tourists per capita than any country in Europe.

Why does no one ever come here? How can this be? Can you get food that isn’t variations on lard?

Well, now here I am, in the quaint, crumbly, airy little capital of Moldova, Chisinau, which is famous for… not much. The main river, the Byk, is more of a rusty stream at the end of someone’s garden. Parts of it, even close to the center, make you feel like you’re in the middle of the countryside: horses in yards, more goats on strings. Incredibly, 70 percent of it was destroyed during the wars of the 20th century.

The great Russian poet Pushkin was exiled to this sultry corner of the then Tsarist empire (there’s a sweet little museum dedicated to his brief stay) and found the houses ‘dirty’ and ‘sinful’ when he begged to be moved to the more exciting Odessa; although it must be said that the sin was mainly his fault as he diligently worked his way through the fair Moldovan womenfolk.

And yet, despite all this, Chisinau has real charm. Yes, there are a lot of post-Soviet tower blocks, but the people are friendly. The best hotels are luxurious and offer good value for money. The many spick and span parks can be wonderful. And, as my extrovert guide Natalje shows me, there are al-fresco cafes everywhere, taking full advantage of that sweet weather.

And the food isn’t “versions of lard”, it’s a vibrant and tasty collision between Balkan and Slavic, Russian and Turkish, plus a spicy genius all its own. The rich complex cuisine speaks of Moldova’s complicated history: swapped between empires, conquered by all – and they all brought their own recipes. If you want trendy “Chisinau fusion” try Divus restaurant, it’s really good; if you want comfort food, have a bowl of Zama, a noodle-meat-umami broth served with sour cream, chili, pickles and bread; it is widely available and costs only a few cents.

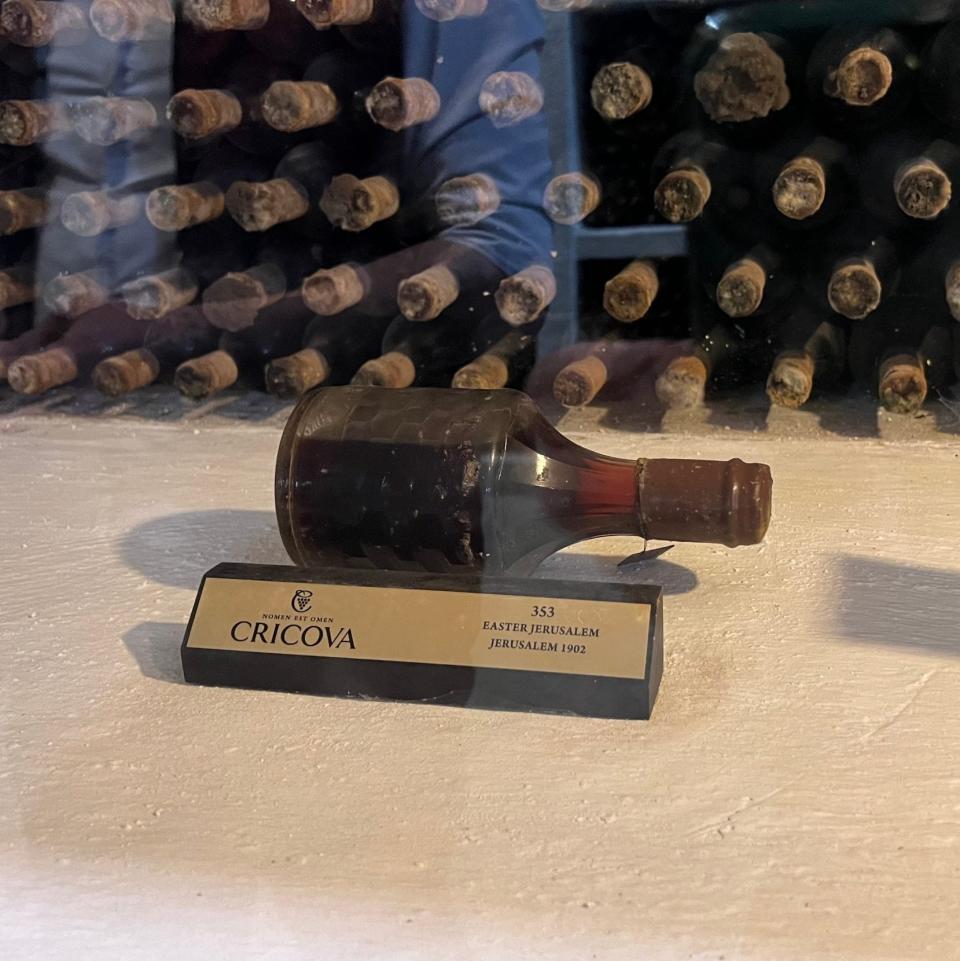

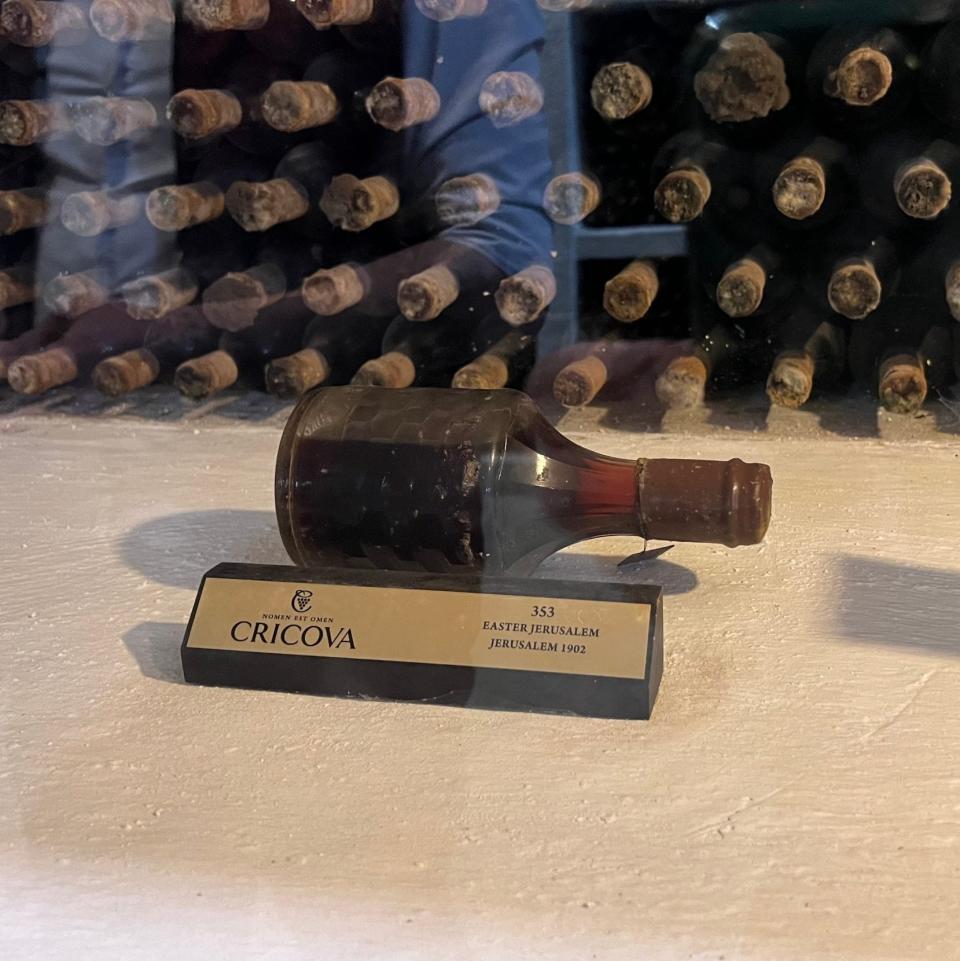

Moving on to Moldova’s next selling point: the wine. We drive through rolling meadows and forests – tiny Moldova has no coast or mountains – and head towards Cricova. The word Cricova comes from the word ‘scream’ and legend has it that the scream was that of an Orthodox hermit: afraid that the Ottomans would steal his wine. Fortunately, the Ottomans failed, because beneath Cricova are 125 labyrinthine kilometers of limestone mines, now the second largest wine cellar in the world. The caves are deep underground and it is always 14C.

On your airy golf cart tour, you’ll see famous private wine collections, a thank-you letter from the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, and Hermann Göring’s wine stash—retrieved from the Nazi leader’s private train at the end of World War II. Some of the tunnels have been transformed into spectacular caverns of crystal and neon; at the end, you can buy more wine—white, red, very good sparkling—at reasonable prices. As I wander around the shop, Natalje whispers, “In Moldova, we don’t tax wine. Because wine is food.” In which case, I’m hungry.

From here it’s a short drive to another famous but very different winery – the chic Purcari. This is the brand of wine that Queen Victoria and all British royals have loved since. Their chic castle-cum-hotel looks like something out of the Rhone Valley and overlooks its own rustling green vines. The restaurant is excellent – especially the crab ravioli. If you’re staying overnight, try the luxurious Tower Suite with its mezzanine hot tub, from which you can kick back in capitalist bubbles – while looking out over the USSR.

Yes, the Soviet Union. The next morning Natalje says to me: ‘I have to behave’, because ‘now we are going to the old Soviet Union. No pictures of guards!” As I get into the car, my phone hidden, I watch as we drive into the quasi-independent exclave of Transnistria: a sliver of pseudo-nation still loyal to old communist Moscow (and which the FCDO advises against visiting – see below).

To be honest, it’s less dramatic than I’d hoped. The border guards gape, the sun-drenched line is three minutes long and then we are in the time-warped Soviet Union, past the mighty Bendery Fortress – once Ottoman, then Swedish, then Russian, a crucial place in military history. It’s a good place for spectacular views, outdoor movies or a summer dip in a big bend of the Dniester (but be careful, the water is fast).

And Transnistria? Yes, they have a statue of Lenin. But they also have a statue of Harry Potter. Yes, they have an old T34 Soviet tank, but they also have a bustling market where you can buy the best cherries, the freshest herbs, plus pickled tomatoes, smoked river fish, wild chamomile honey and cups of cold kvass (weak bread beer). is strangely refreshing on hot Moldovan days.

For lunch we stop at “Back in the USSR”, a Marxist themed cafe that, unlike any other themed restaurant in the world, serves excellent food – especially the amazing borscht. It costs £2 a bowl and you eat it while staring at a Bakelite Stalin.

From Transnistria we go back to the deep history of central Moldova – and Orheiul Vechi. Here in this Eden Valley, full of quaint wooden guesthouses and “nationalized walnut trees” (according to the always entertaining Natalje), I eat fresh cherry pie for breakfast. Next to a 19th century farmhouse. Next to a 16th century cave church. Next to a 14th century Tatar caravanserai. In addition to the “Geto-Dacian walls” from the 3rd century BC. Next to 20,000 year old Neolithic remains. All made from rocks full of 20 million year old fossils. I am honestly surprised that it is not on the UNESCO list: perhaps, like so many other parts of Moldova, it is simply overlooked.

Last stop, best stop. It’s a modest farm on the banks of the Dniester, owned by a remarkably friendly couple named Sergiu and Emilia – and their assorted descendants. After Emilia shows me how to make “the smallest sarmale in Moldova” (fine cabbage rolls) in her Hansel and Gretel kitchen, we think about walking, boating, cycling or maybe horse riding – all of which are possible – but while it is gently drizzling , Sergiu takes me into his man cave: a gloriously moldy cellar filled with all things fermented, barreled and distilled, including 118 varieties of house-made vodka.

Sergiu doesn’t speak English; I speak even less Moldavian, but Sergiu explains – via Natalje – that if we drink enough alcohol, it doesn’t matter at all. Oh well, it must be worth a try. Ahem.

Turns out he’s right. As Sergiu exuberantly offers shot glasses of mulberry vodka, pine needle vodka, strawberry vodka, “medicine vodka”, “78 percent proof” vodka and “at this point I forgot to take notes” vodka, we start chatting in a specially drunk Esperanto before exuberantly into urgent anthems erupt, and then I finally stumble home, chuckling, to my rustic wooden room—and when I wake, I hear roosters crowing, donkeys coughing, and Sergiu’s extended family. On the sunny balcony, Emilia serves warm home-made bread: with rosehip jam and fresh cottage cheese.

And as I sit there with a slight hangover and a nice strong coffee, staring at the silver mist rising from the Dniester, Sergiu comes over, shakes my hand and hands me a free bottle of raspberry vodka. Apparently it was my favorite (my memory is hazy). And as he does so, I think: what a nice guy, what a nice family, what a nice country. Because it’s true: absolutely everyone I met on this trip was nice, and that really is something special.

In a world where tourists are increasingly shunned, interrupted, taxed, cursed and industrially processed through sterile resorts, Moldova is a place where they welcome you with joy, because they get so few tourists and because they really want to see you. In other words, visiting Moldova is like coming home to the warm and funny family you forgot you had. Fantastic.

How to do that

Regent (www.regent-holidays.co.uk; 0117 453 3001) offers an eight-day Moldovan vineyards and villages tour, taking in the rich cultural heritage of Chişinău, the enigmatic allure of Transnistria and the rustic charm of Moldovan villages, with wine tastings and ancient monasteries along the way. It costs from £2,825 per person and includes flights, three nights in a four-star hotel in Chişinău (one at the start of the trip, two at the end), a further four nights in a variety of family-run guesthouses or boutique hotels, plus some meals and guided tours.

Note that while the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) has no warnings for Moldova, it advises against all travel to Transnistria. Ignoring FCDO advice may invalidate your travel insurance.