Apple TV+’s alternative space race, For All Mankind, imagines what would have happened if cosmonauts from the USSR, not NASA astronauts, had been the first to land on the moon. Instead of the waning interest in space that followed the moon landings in our reality, the race has continued throughout the show’s four seasons thus far toward the moon and then the settlement on Mars.

In the final season, the finale of which aired on January 12, 2024, the initial colonization efforts on Mars have developed to the point where an international alliance is supporting and maintaining one large colony. The city on Mars, called “Happy Valley,” features a series of interconnected modules.

Tubular corridors run between larger geodesic and half-pipe structures that house control rooms, laboratories, meeting rooms, and dining and living areas for the base commander and other higher-level groups. Most residents live underground.

With its Artemis program, NASA plans to allow humans to live beyond Earth’s orbit. This would include a lunar base camp, as well as a space station orbiting the moon, with the intention of eventually sending humans to Mars. People have long dreamed – and scientists experimented – about what structures such Martian explorers would live in.

Living on Mars?

In the early 20th century, enough uncertainty remained to allow for planetary romances such as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom novels. Written between 1912 and 1946, these tell the story of a 19th-century American veteran transported to Mars, and were brought to life in the 2012 action film John Carter. These fantasies paved the way for more serious consideration of survival on Mars as our understanding developed.

However, astronomers had already determined that the planet’s surface was arid, cold and toxic. Long before Burroughs completed his series, it was clear that the great cities of Barsoom, open to a breathing atmosphere, could never exist.

One of the first stories to seriously consider the scientifically understood conditions on Mars, and the life that might emerge from them, was Stanley Weinbaum’s 1934 novella, A Martian Odyssey. Consistent with telescopic observations of the planet’s cold, thin air and spectra indicating a lack of both water and vegetation, this was a Mars without cityscapes, but not without life. Trying to salvage what he can from a crashed shuttle, the main character treks 800 miles across the Martian landscape, encountering a variety of interesting Martian shapes.

In the early 20th century, Mars’ atmosphere was believed to be thin, but not necessarily beyond the reach of human adaptability. After all, settlements on Earth exist at altitudes of up to 5,000 meters – where atmospheric pressure is less than half that at the surface. Early estimates for surface pressure on Mars were in this range (rather than less than 1%, as we now know). Weinbaum thus speaks of “months spent in acclimatization chambers,” but otherwise frees his explorer (and every settlement on Mars) from the needs of atmosphere management.

Going underground

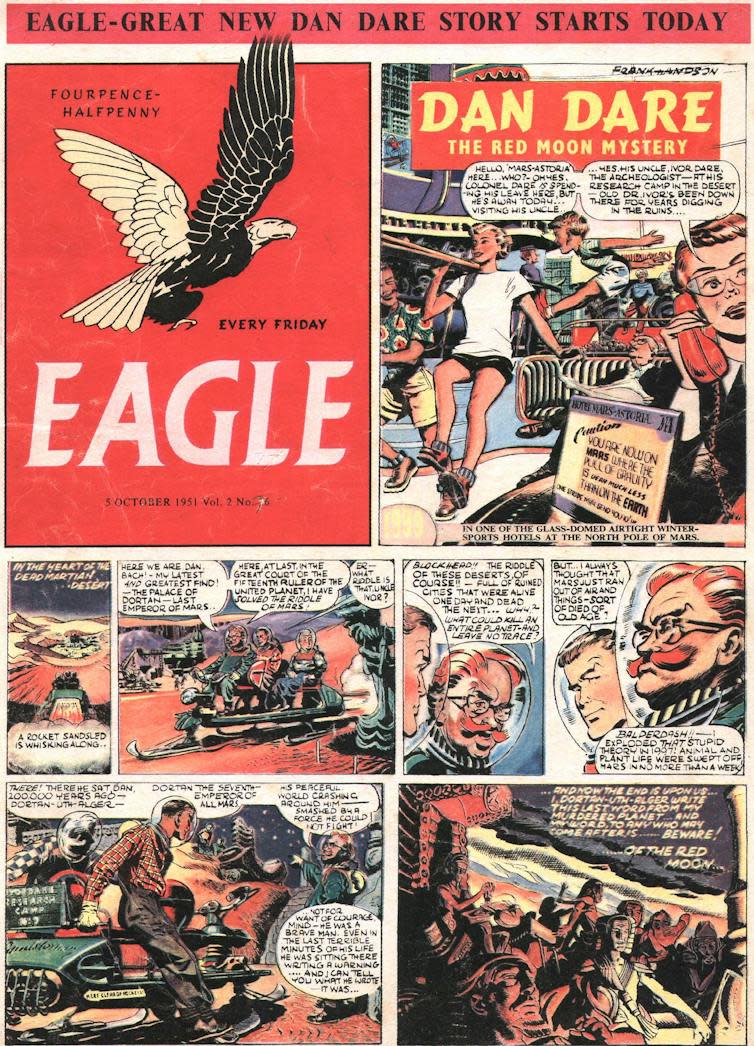

By the mid-20th century, observations on Earth and the first of the Mariner probe missions had removed any doubt about the hostility of the Martian atmosphere. The cities that mid-century science fiction writers envisioned were surrounded by enormous protective domes. These could contain an Earth-like environment and allow people to breathe and move freely without protective equipment.

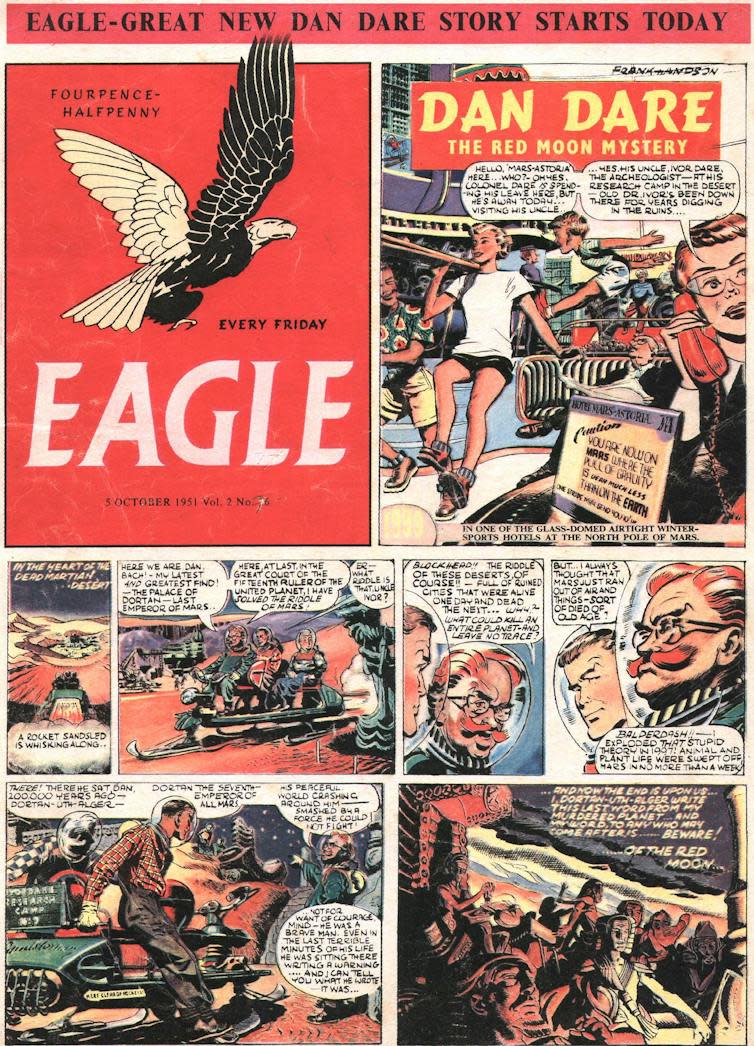

Such domed surface cities can be found in examples ranging from children’s books such as Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future, to the work of established authors including Larry Niven (see his 1966 story, How the Heroes Die). Some saw these domes as completely urbanized. Others imagined a more dispersed settlement, amid a managed landscape.

This dominant image of Martian cities persists to this day, in images from Mars colonization enthusiasts including the international Mars Society and SpaceX. However, research shows that a dome-shaped environment would have significant shortcomings as long-term habitation.

Since the 1960s, scientific insight into the impact of radiation on people and their descendants has increased. The planet lacks the protection that Earth’s thick atmosphere and strong magnetic field provide to our DNA from a shower of ionizing particles from the sun and beyond. Smart dome materials can filter some of this, but cannot protect astronauts from the cumulative effects of invading particles, leaving occupants vulnerable to cancer.

As pointed out by many writers (including Niven in the story already mentioned), large domes would also make a Martian city vulnerable to air leaks, as well as to the extreme swings in day-night temperature that the planet experiences (from -125ºC to 20ºC) . ). Furthermore, the material would be abraded over time by sandstorms so extreme that they are visible from Earth.

Instead, many researchers now consider underground or cave settlements as sites for human settlements on Mars. Here, protection from temperature, radiation, sandstorms and air leaks is provided by a thick layer of regolith (soil or rock), reducing the cumulative exposure that settlers face.

Although the red planet now has no surface water, it is likely to have cave systems dating from its wetter, tectonically active youth, and – unlike Earth – its surface earthquakes are rare and weak. If natural caves are not available, digging a tunnel or even using surface rock powder to create a form of Mars concrete can be a good alternative. Partly with Mars prototyping in mind, NASA and ESA have explored the idea of 3D printing and then burying habitation modules on the moon, which poses many of the same risks.

For All Mankind is known for its realistic physics. The production team consists of a technical advisor from NASA.

It is perhaps not surprising that the Happy Valley colony, which descends several levels into the Martian subsurface, represents a plausible vision for future cities on Mars. However, unlike the series, underground levels may well be sought after by actual Martian residents due to the increased protection they provide.

Planetary settlement remains an increasingly remote prospect in our reality, but science fiction has always played a role in shaping public understanding of our planetary neighbors and in inspiring enthusiasm for their exploration. Just as Burroughs’ Barsoom novel inspired the scientists who worked on the Mars landers in the 1960s and 1970s, today’s viewers of For All Mankind could also include the engineers and scientists who will one day bring his vision of a Martian city to fruition to take.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elizabeth Stanway receives funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council for her astrophysics research