Wow! Here’s some great news, guys. Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, stars of the beloved and endlessly quotable 1989 comedy Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, are reuniting next year—not for a cynical movie sequel or reboot, like everyone else in Hollywood, but for a new Broadway production of Waiting for Godot. Yes, that’s right: It’s Bill & Ted’s Existential Stage Adventure.

At the helm of this smashing revival is the man of the moment Jamie Lloyd, the British director known for his expert celebrity maneuvering. Lloyd’s multi-Olivier-award-winning Nicole Scherzinger-led retelling of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Sunset Boulevard comes to Broadway this fall, and his Romeo & Juliet was the West End’s hottest summer ticket thanks to the casting coup of Spider-Man actor Tom Holland.

Still, Lloyd’s choices are sometimes eyebrow-raising. I must admit that I was one of the doubters when Scherzinger, a former member of the Pussycat Dolls, was chosen to play Norma Desmond – although I’m just as happy to admit that I was completely wrong. Scherzinger was a revelation.

So while the duo best known for their comedic tricks as the amiable Bill and Ted (teenage slackers who use a time-traveling phone booth to skip their high school history class) might not seem like an obvious choice for Samuel Beckett—not to mention that this is Reeves’s professional stage debut and Winter’s first time back on Broadway since 1981—I trust Lloyd’s impeccable judgment. Plus, there’s actually more in common between their zany three-film franchise, which features futuristic robots and Genghis Khan trashing a sporting goods store, and Beckett’s revered existential meditation than you might initially think.

The production was Reeves’s brilliant idea, according to the New York Times , but once he pitched it to Lloyd, the director considered it a “no-brainer.” Part of Lloyd’s reasoning is that Waiting for Godot lives or dies on the chemistry between its two central characters, Vladimir and Estragon, and we already know that Reeves and Winter shine as believable buddies who trade some banter.

“Their instant chemistry, their shorthand and their friendship will be so valuable,” Lloyd explained, adding, “Those characters find solace in their camaraderie as they stumble toward the void.” That element, he suggested, will be “the central thesis of the production,” which sounds like a winning strategy to me.

Beckett’s 1953 play is also, let’s not forget (and some fake productions do), fundamentally a comedy, albeit a dark and deeply thought-provoking one. Reeves and Winter’s mastery of their films’ deceptively awkward, dry stoner humor bodes well: all they have to do is transition to older and bleaker, but not necessarily wiser, versions of those characters, which shouldn’t be hard, since the actors have their own later-life experiences to draw on. Age—and with it life’s big questions—comes to us all, even Bill and Ted.

But even that last aspect should suit them: their blockbusters, though filled with jokes about the idiocy of their bozo protagonists, were oddly well-versed in philosophy. During a visit to ancient Greece, Ted befriends Socrates (or “So-crates”, as they call him) by quoting a Kansas song: “All we are is dust in the wind, dude”. The duo happily adopts the philosopher’s premise that “the only true wisdom is knowing that you know nothing”.

Bill & Ted is also sharp on the ethics and education of time travel, and the transience of existence, with Bill ultimately musing that “the best time to be is now.” Their calm response to their dizzying escapades could be read as a paean to stoicism, and we could all do worse than adopt their core philosophy: “Be great to each other – and party on.”

It is worth considering, however, why Godot has become the play of choice for any actor worth his salt. Before Reeves and Winters perform, we will see Ben Whishaw and Lucian Msamati team up for a West End revival in September.

It’s an admirable choice in a way, because it’s not a natural show-off piece – unlike, say, a flashier Shakespearean role or a more accessible Noël Coward comedy. You don’t get to deliver a beautiful verse, deliver witty bon mots, attempt a sword fight or go to extremes in an obviously award-baiting way.

Instead, Godot is a devilish challenge – the ultimate tonal balancing act. Play it too straight and it becomes a dull slog, but go too comically broad and you risk undermining the big ideas. It’s easy to see when Beckett is badly played, but hard to define what constitutes a truly great interpretation.

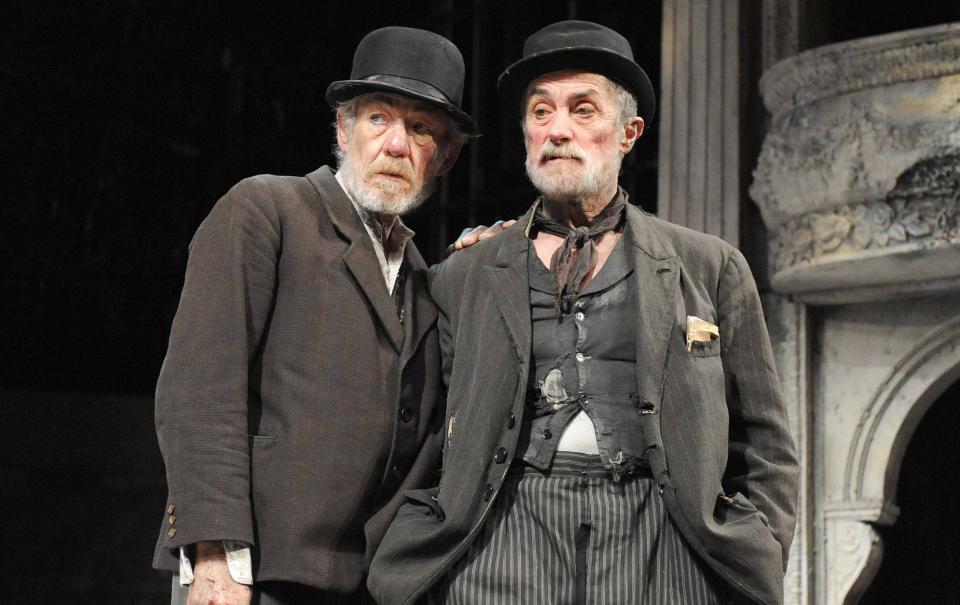

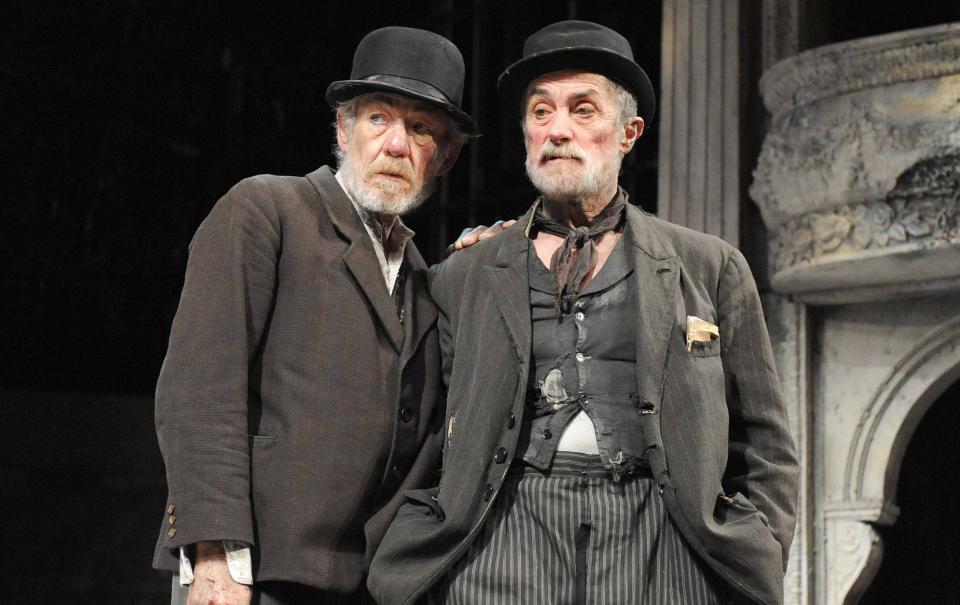

Well, difficult but not impossible. I remember being captivated by the vaudevillian duo of Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart in Sean Mathias’ 2009 West End production, who lured you in with their deft clowning and then proceeded to mock you with their palpable sense of sadness.

But Godot can trip up even the most talented actors. Comedy greats Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson were criticized for their winking complicity with the audience when they filmed it in 1991, as were Steve Martin and Robin Williams during its off-Broadway run in 1988. Frank Rich of The New York Times despaired of Williams’s “frenetic horseplay,” whether he was “using cowboy-movie accents and droll props” or singing the Twilight Zone theme music.

Conversely, I have listened to a number of endless versions in which the actors seemed determined to convey that they did indeed fully grasp the weighty significance of Beckett’s metaphysical exploration. This is equally fatal: Godot must not be solemnly presented as a dusty academic treatise.

But perhaps that challenge is what continues to draw artists to the piece. To not only master it but to put your own stamp on it is a greater achievement than just churning out a decent “To Be or Not to Be.” You’ve demonstrated an artistry that comes from your heart as well as your head, and you’ve skillfully juxtaposed absurd humor with elemental despair.

Has Lloyd picked the perfect righteous couple to do just that—and sell a whole new generation on Beckett in the process? I think this could be a genius concept, and I have faith that Reeves and Winter can walk that tonal tightrope with Bill and Ted-like ease. Watch out, Broadway: here comes a prime Godot.