As one of the world’s most spectacular natural wonders, the Great Barrier Reef is subject to intensive research. It covers an area of approximately 133,000 square meters, larger than Great Britain, Switzerland and the Netherlands combined. Yet in recent years it has received less attention for its richness, color and wonder, and more for the fact that it is “dying” or “dead.”

Competing claims suggest that on the one hand you should see the reef before it’s too late (a 2017 study published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism claimed that 69 percent of visitors to the reef were motivated by ‘last chance tourism’) and on on the other hand, it would be irresponsible or unethical to visit it at all.

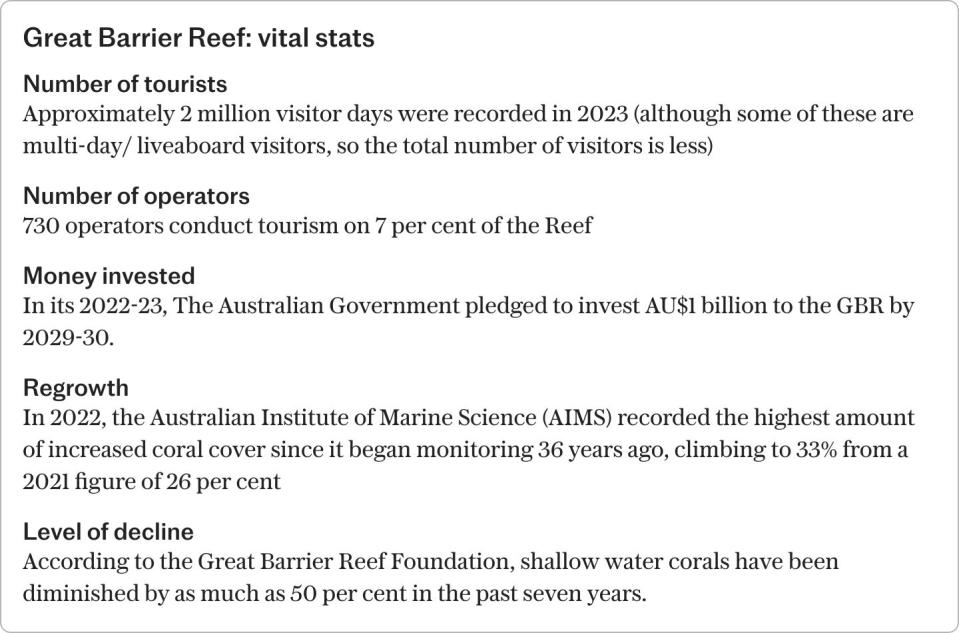

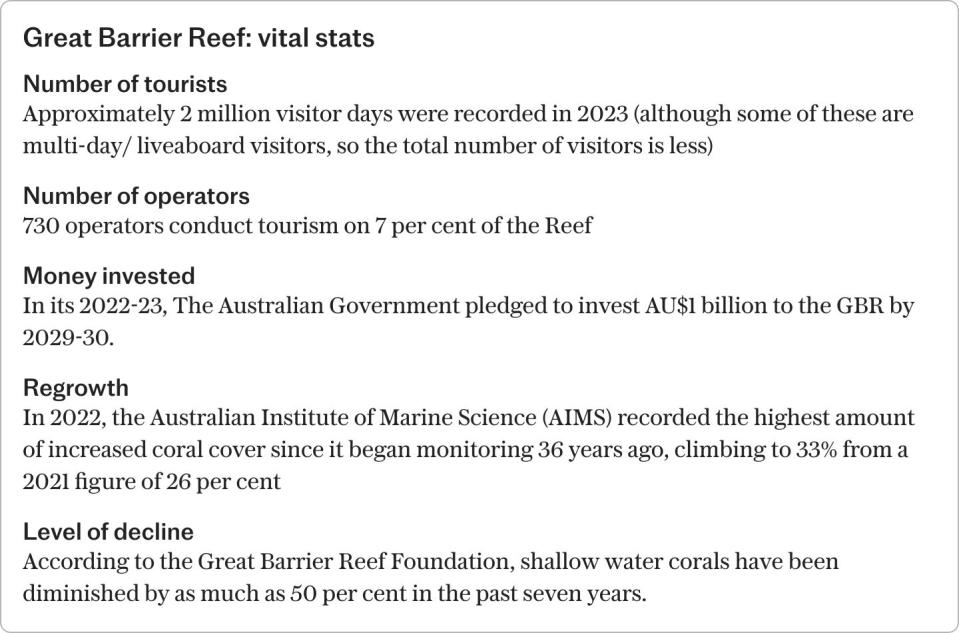

What is not often realized, however, is that only 7 percent of this vast area is used for tourism. Nor do we often hear that no new licenses have been granted to operators (each of which has a designated dive site) since 1997, or that visitor numbers are carefully managed.

That doesn’t mean the reef isn’t in trouble. Rising sea temperatures and rapid succession of bleaching events have had a terrible impact, as have violent storms and outbreaks of predatory crown-of-thorns starfish, which feed on coral polyps.

Cairns is the “gateway to the reef” of tropical North Queensland and it takes about 90 minutes to reach most dive sites. The trip gave me plenty of time to ask Alan Wallish, MD and founder of the Passions of Paradise catamaran, for his thoughts on the future of the reef. He has been operating here for 30 years and his love and knowledge of the underwater realms are evident, as is his desire to preserve and restore it.

Our timing was unfortunate in one respect; blameless in another. “My phone has been pinging all day,” he said ruefully. On the day of our excursion, another mass coral bleaching event – the fifth since 2016 – was reported by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), in partnership with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

“This will be the headline that the news media will have to deal with,” he said, “but there is a real need to counter the negative information with other realities of the situation.”

An example of this? I had always assumed that bleached coral was dead coral, but that is not the case. “As temperatures rise, coral becomes stressed and responds by expelling the algae that give it color,” Wallish explains. “Provided temperatures drop – as you would expect after the summer – they can recover, and they have done so repeatedly.” As delicate and otherworldly as it seems, coral is (or can be) surprisingly resilient. According to Ryan Donnelly, CEO of the Reef Restoration Foundation, coral fragments “grow back more strongly, with all coral having a natural adaptability.”

In 1997, as part of the federal government’s $15.1 million Tourism Reef Protection initiative, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority launched Eye on the Reef, a citizen science program. Passions of Paradise initially only offered this reef tour experience as a weekly addition, but thanks to demand from snorkelers and divers alike, it now operates daily.

Accompanied by a “Master Reef Guide” and equipped with a waterproof clipboard and pen, I descended into a vibrant but silent world and began conducting a survey, the results of which would be sent to a central hub and combined with observations from others underwater researchers. .

We counted both fish and coral; the former would not perform their quicksilver dances in such clouds of color if the latter were not in reasonable form. Even the presence of sea cucumbers, unattractive as they are, is reassuring: they are sometimes called the “janitors of the sea” and play a crucial role in the health of the reef.

Nevertheless, back at the Marlin Marina in Cairns, the crowd is overwhelming. The sheer number of boats waiting to welcome visitors aboard seems unsustainable. In a climate where overtourism is known to threaten the beauty and even survival of some destinations, it is no wonder that reef tourism is raising eyebrows.

Every tourist pays a ‘reef tax’ in their exploration costs – money earmarked for replanting and research. Furthermore, as I discovered on my recent visit, many of the operators are powerful not only in their fight for the health and recovery of the Great Barrier Reef, but also in their determination to raise awareness of its resilience.

Several ships have been given eco-certification and the expected warnings about not touching, removing or awkwardly kicking the coral. We listened to educational talks on board about reef health and conservation. Certainly, there was nothing like that on the dive-ship-and-booze cruise I embarked on long ago.

I have also learned that there are limits to what is perceived when news of bleaching first hits the news. The surveys – not to be confused with Eye on the Reef – are conducted by trained observers, not citizen scientists, but their first aerial observations reveal only the uppermost corals, in the warmest waters.

Furthermore, the vast majority of visitors to the reef will witness it via a glass bottom boat (a “glassy”, as they are known locally) or snorkeling, increasing the risk of negativity. Diving to 18 meters, the maximum allowed with a Padi Open Water certification, or to 30 meters, as an Advanced Diver, gives a more colorful perspective.

“Professional magazine photos are preternaturally vivid,” the crew explained on a Sailway trip from Port Douglas, “but what you rarely realize is that huge underwater lights are used, making the sea and coral look brighter – and that’s even before photoshopping. It creates unrealistic expectations that, combined with reporting a state of emergency, risks causing people to stay away.”

I can’t stress this enough: the Great Barrier Reef is in trouble, just like every reef in the world, and what makes this even more worrying is that it sits next to a fiercely protected World Heritage Site, The Daintree. Rainforest. It is devastating to think that a CO2 vacuum of this size (approximately 463 m²) is not enough to halt acidification; that someone who has never visited the reef and may never visit will impact the health of the reef in a way that someone who visits responsibly may not.

Essentials

Sarah Rodrigues was a guest of Tourism Tropical North Queensland and Tourism Australia.

Luxury operator cazenove+loyd offers tailor-made trips to Tropical North Queensland, with eight-night stays at the Shangri-La Cairns and Sheraton Grand Mirage Port Douglas, including transfers, local guides and a Great Barrier Reef trip from £3,000 per person . Flights start from £919 with Singapore Airlines.

The Passions of Paradise Great Barrier Reef tour and Marine Biologist for a Day program cost $410/£213 for snorkelers and $510/£265 for divers, including two dives.