When a great Shakespearean actor delivers his immortal lines, it’s as if the words come spontaneously, refining our understanding of the play, deepening our appreciation of the human condition, even defining our age. It can also feel dizzily, as if you’re in touch with Shakespeare’s mind, which contained, to quote Hazlitt, “a universe of thoughts and feelings.”

Where are the great young Shakespeareans of today? When Laurence Olivier starred in Henry V on screen in 1944, he rallied wartime morale and cemented Shakespeare at the heart of our national story. When Kenneth Branagh made a splash in the role at the RSC 40 years later, he was hailed as the “new Olivier” (Charles and Diana were so impressed with his performance that it has been suggested that Prince Harry was given the name as a result).

Back then, Shakespeare was still the epicentre of our cultural life. Although Charles is now on the throne and Shakespeare lends institutional gravitas on stage (he is a patron of the RSC), the landscape seems far less fertile, even disturbingly patchy.

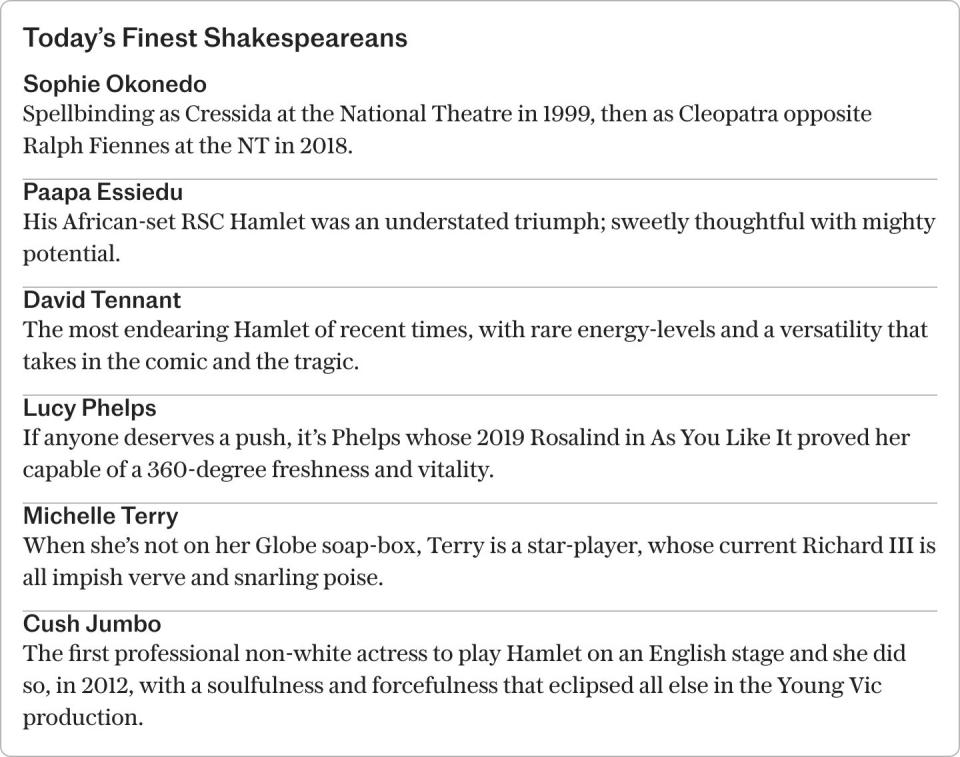

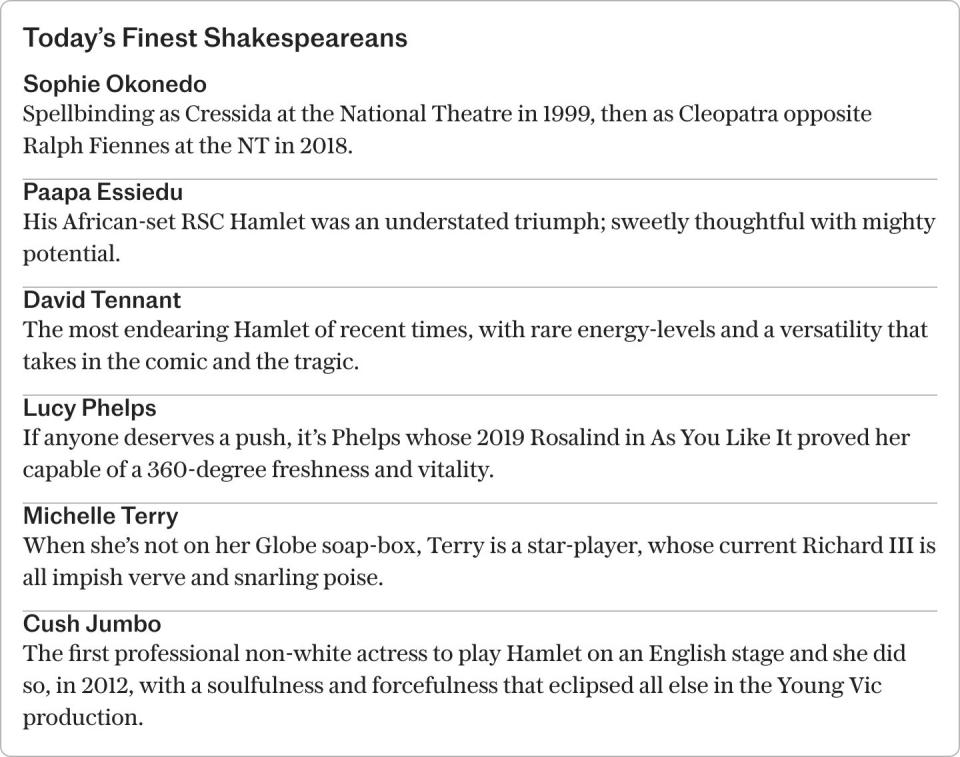

When Ian McKellen fell off the stage playing Falstaff last month, an accident that ended his tenure with Player Kings prematurely, it was not only an alarming moment for him and his many fans, but a wake-up call for the general public. At 85, he is our greatest living active Shakespearean, but it is as if he has pushed the limits of his endurance; his equally revered contemporaries Judi Dench and Derek Jacobi are no longer seeking these roles on stage. Where are their successors?

One reason, I think, why there was so much outrage surrounding the Tom Holland-led Romeo and Juliet – which drew the most bitterly divided critical response in years – is that Holland seemed to embody a new kind of have-a-go Shakespearean. Here he was – 27, almost 28 – thrust into the heart of the West End, in effect, on the back of his global fame as Spider-Man.

You could argue that director Jamie Lloyd deliberately tailored the performance to the debutant’s inexperience – the abbreviated lines were often delivered in little more than an amplified mumble. The provocation undoubtedly got people talking. But effectively parachuting a famous face is a far cry from the days of hopeful actors climbing the ropes.

People like Dench, Jacobi and McKellen embraced Shakespeare as if their lives depended on it. They understood that alongside the demands of quick intelligence, physical stamina and substantial emotional and vocal range, the complexities of the characters and the demands of the language required gruelling application. From that moment on, the world was your oyster. Michael Parkinson’s 1975 interview with Helen Mirren remains notorious for its sexism – but what is striking is that she is introduced as a creature of the stage, the new queen of the RSC.

You could at least say that Lloyd’s next venture – announced this week , which will bring Shakespeare to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, for the first time since 1958’s The Tempest (starring John Gielgud) – is a nod to that traditional route. Yes, Sigourney Weaver, playing Prospero, represents Hollywood A-list casting (though she was last in Shakespeare off-Broadway in 1986).

But Tom Hiddleston, opposite Hayley Attwell in Much Ado About Nothing, made his mark in Shakespeare. His talent was spotted by Cheek by Jowl, and he was later an intense Coriolanus at the Donmar (2013) and also an acclaimed, albeit brief, Hamlet at Rada (2017), his alma mater, directed by Branagh. The latter gave him the “red book”, a copy of Hamlet passed down the generations by the Victorian actor Johnston Forbes-Robertson in a ritual of anointed inheritance.

Yet it can hardly be said that he has yet established himself as Olivier’s true heir. And if he has sunk his teeth into Shakespeare, many of his colleagues seem merely to floss with it.

A striking example of this is Ben Whishaw, as compellingly feverish as Hamlet 20 years ago, aged 23, at the Old Vic. Apart from his distinctive work in the BBC’s Hollow Crown series, that early-stage potential has not been fulfilled. Eddie Redmayne, for example, was a brilliantly sensitive Richard II at the Donmar in 2011; the crown was there for the taking, but he didn’t seize it. Benedict Cumberbatch, who spent two formative seasons at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre, caused a storm at the Barbican box office when he played Hamlet in 2015, but has failed to capitalise on the sensation.

Likewise, his Sherlock colleague Andrew Scott played the role with equal finesse at the Almeida, but it remains his only Shakespearean appearance. Most astonishingly, Matt Smith – who succeeded the ever-exciting (RSC alumnus) Shakespeare stalwart David Tennant in the Tardis – told The Telegraph in 2012 that the Bard was on his to-do list; there hasn’t been a peep since.

What a contrast with Simon Russell Beale, Ralph Fiennes and Harriet Walter, who still devote themselves to Shakespearean work as if it were the core of their careers.

What’s going on? In part, streaming has made on-screen work more lucrative, and so young superstars can be more choosy. The ladder to Shakespeare fame is also less stable than it once was: touring and regional theatre have suffered a decline, while the big companies have not been bastions of star-making excellence.

The National under Peter Hall, Richard Eyre and Nick Hytner carried the torch (with Adrian Lester’s Henry V a bright light at the start of Hytner’s reign), but Rufus Norris has let it slip somewhat. At Stratford, after the upheavals at the end of Adrian Noble’s reign in 2003, the RSC affirmed an ensemble ethos under Michael Boyd, with consolidation as its watchword under Gregory Doran.

There were some decent actors emerging during this period – think Jonathan Slinger (a fine Richard III) or Jonjo O’Neill (a memorable Orlando) – but grabbing the audience’s attention? That was often left to the combative Antony Sher (Doran’s late husband).

Perhaps the biggest change in our time is the rise of gender-flipping and gender-blind casting. While there are historical precedents, this trend has expanded the range of leading roles for women and inevitably narrowed the standard pool available to men.

The debate around the world, with its content-heavy warnings and anti-racism seminars, underscores a broader cultural tension in Shakespearean performances. On the one hand, the emphasis has always been on pushing things forward – a shift captured beautifully by Jack Thorne’s The Motive and the Cue, when in 1964 Gielgud “handed over” Hamlet, the part he had once made melodically his own, to Richard Burton, who was keen to put his own wilder stamp on it.

What plagues the scene today, however, is perhaps a new reluctance to put a strong stamp on roles and the canon as such; the idea of dominance can seem patrician in itself. Who didn’t get to play the part, rather than who got it and how they played it, is often the nagging question. The “star” becomes a statement of representational intent; the director often has a free hand, the actor is more on the line.

Michelle Terry, who defied convention by playing Henry V at the Open Air Theatre (they rarely make time for Shakespeare these days), found herself in the firing line this year when she took on Richard III at the Globe, a theatre now the domain of disabled actors with the right life experience.

Yet we must resist the creeping prevalence of single turns over sustained engagement, and while diversity and inclusion are crucial, they are not the only yardstick. It will be a growing tragedy if the most exciting crop of Shakespearean actors falls prey to a zeal for egalitarianism, however well-intentioned. The clock is ticking; Branagh was only 28 when he brought Henry V to the screen; in 1958, Gielgud was 53, his defining glory behind him.

There is still reason for hope. This week, Alfred Enoch takes to the stage in Pericles in Stratford. Not only does he have some sneaky Shakespeare experience (he was best in the Globe’s 2017 socially worthy Romeo and Juliet ), he also has some sensible things to say about the work itself. He recently told The Telegraph that he’s not so interested in contemporary parallels: “You don’t want to pigeonhole the play if you can help it.”

Perhaps at 35 he can be a model for the future; graceful, modest, and conscientiously in the grip of the work. Such quiet stars need nurturing and showing off. Every generation will lose some of its stage giants too early – (Daniel Day-Lewis crumbling halfway through Hamlet , Anthony Hopkins tiring of Lear , Helen McCrory, a dazzling Lady Macbeth, gone before her time) – but there must be a new mood of devotion and support for them across generations.

Coleridge famously said of Edmund Kean (1787-1833): “To see him play was like reading Shakespeare through lightning bolts.”

Styles have changed, but we still long for that revelatory lightning. Let’s hope some of it strikes with force at Drury Lane.

‘The Tempest’ is at Theater Royal Drury Lane from December 7, ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ from February 10; lwtheatres.co.uk