The opening night of Dodie Smith’s Dear Octopus at the Queen’s Theater on September 14, 1938, unveiled against the backdrop of Hitler’s maneuvers in Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland, was unlike almost any other West End opening before or since.

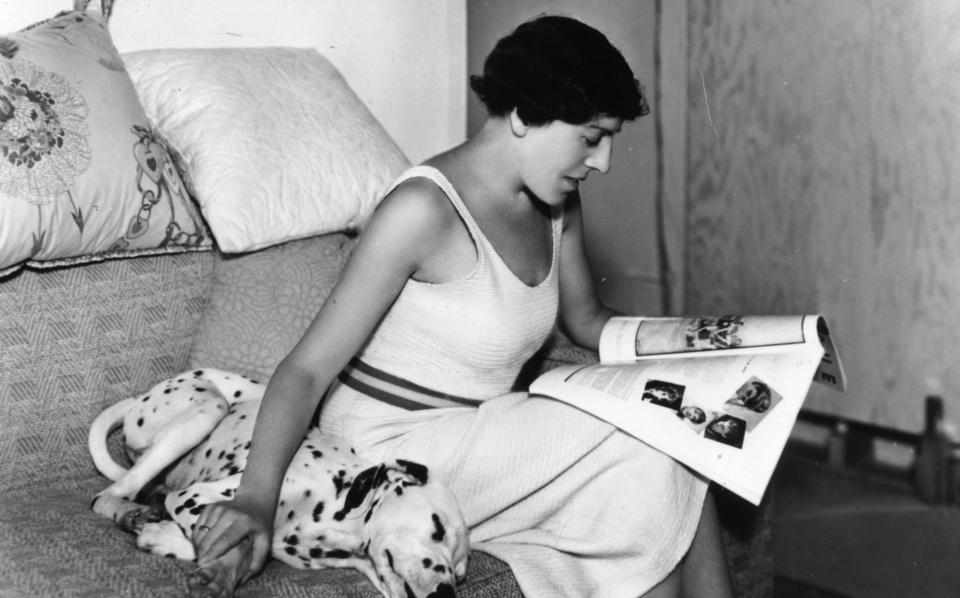

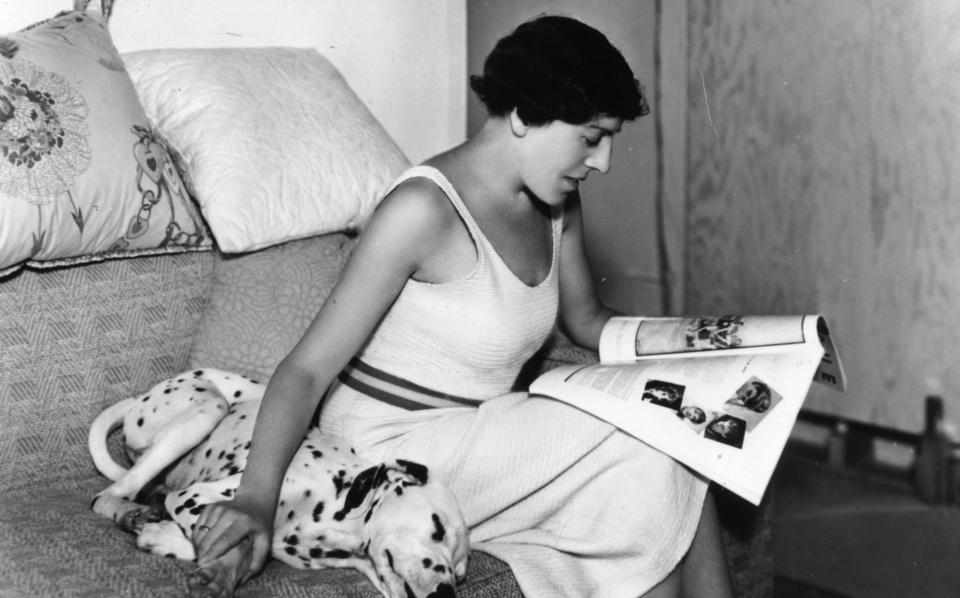

The subject could not have been further removed from the gathering clouds of war – it focused on a family reunion for a golden wedding anniversary in a country house – and yet that grim shadow infiltrated the room. As Valerie Grove wrote in her biography of Smith, later known as the author of The Hundred and One Dalmatians: “For the first half the house was subdued, the faces were grave and there was little laughter… Then, in the first intermission, [a critic] arrived… with the news, spreading like wildfire through the theater, that Chamberlain was flying to meet Hitler at Berchtesgaden… It was as if the entire audience breathed a sigh of relief. From that moment on the game went excellently.”

The rest is cataclysmic history. And it was as if when the curtain fell on the play in 1940, a veil was draped over the dramatic production of the 1930s. Few remember the success of Dear Octopus or that Smith was one of the most celebrated playwrights of the 1930s. Or, further, that female playwrights – including Clemence Dane, Molly Keane and Elizabeth MacKintosh – were a force to be reckoned with.

While theater from the interwar period is wrongly labeled as one homogeneous whole, drama from the 1930s is often – if at all – depicted as conservative, frivolous and homely. A casual observer might think that the 1930s begin with Noël Coward’s Private Lives (1930) and end with his Present Laughter (1939), with little in between. There is the perception, to borrow a phrase or two from Coward’s biographer Oliver Soden, of ‘everyone-for-tennis filler’ and ‘crushing middle-class’ interests. That is only partially correct.

Perhaps the biggest stumbling block to admiration is our own (reverse) snobbery. The middle-class milieu and articulation of many contemporary plays – marked by an economic depression following the Wall Street Crash – were identified as problematic after the ‘kitchen sink’ revolution of the 1950s, and we still recoil from it to this day a bit of a throwback, with the thirties. revivals are few and far between. The upcoming staging of Dear Octopus at the National is its first revival since a West End run in 1967.

Yet it is remarkable how daring much of this ostensibly conservative theater actually was. In its expression of bubbling anxiety in the face of accelerating modernity and the overseas threat, it speaks eloquently for its own time, and reaches out to ours with its kindred anxiety.

There was experimentation within drawing room comedies, not least in JB Priestley’s timeslip dramas, in which he observed characters across decades (Time and the Conways) or, most daringly, in Dangerous Corner, creating a Sliding Doors feel of radically different outcomes. And as for Coward, he gave us a play about a bisexual love triangle (Design for Living) that initially couldn’t be staged in Britain, Post-Mortem (which introduces the ghost of a dying World War I soldier) and the short film -play sequence Tonight at 8:30 PM, one of which, the hallucinatory wedding musical Shadow Play, is perhaps the most avant-garde thing he wrote.

Sometimes the experimentation felt like the trop. Although TS Eliot was a poetic titan, his cerebral mission to convert a skeptical audience to the value of verse drama (and also of Christianity) in work like Murder in the Cathedral (1935) has an unpleasant sublimity. Auden and Isherwood’s dramatic adventures have their moments, but suffer from a idiosyncratic quality as they bravely grapple with England’s confused idea of itself.

If we continue to preoccupy ourselves with forgotten masterpieces and neglected dramatic geniuses, we will be on a losing wicket. We can brag about Somerset Maugham, but the Spanish produced Lorca. Yes, we had Priestley, but the Americans had O’Neill. Bernard Shaw declined while Brecht rose. But approach many of the works from this era with respectful curiosity and they reveal a talent to fascinate.

Let’s take Dear Octopus, which takes its title from a grudgingly loving final comment on the institution of the family (“that precious octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape nor, in our deepest hearts, ever quite want”).

Yes, it has an ‘old-fashioned’ veneer: lots of middle-class conversation and little apparent plot, in a Chekhovian key. But Emily Burns, the director of the National Revival (starring Lindsay Duncan as the aging matriarch Dora), asks us to look closer. “Smith received high praise from her contemporaries for precisely this skill – other writers recognized her delicacy and craftsmanship. There is also something radical about putting such a domestic world on stage, at a time when there are all kinds of dismissive prejudices about what women’s writing will be about.”

For director Tom Littler, who has just moved Sheridan’s 1770 drama, She Stoops to Conquer, to the 1930s at the Orange Tree, Richmond, we underestimate these works to our detriment. “What fascinates me about plays from this period is how many things lie beneath the surface. The social form limits the way people can express themselves, but when it comes out it can be shocking, violent and passionate. When a character says, ‘I never liked you,’ it can be explosive.”

Littler finds the mix of different generations in one decade particularly ripe for drama. ‘If you have an elderly person from the 1930s, he or she is from the mid-Victorian period. They can be placed alongside those who lived through the First World War, as well as those born around the turn of the century, who narrowly missed the war, plus those who grew up afterward and who faced the Second World War.”

This dynamic predominates in Dear Octopus and exists to a certain extent in Terence Rattigan’s After the Dance (1939), a portrait of a failed marriage between two bright young people, where affected cheerfulness still plays, but suicidal despair lurks. It was successfully revived by Thea Sharrock at the National in 2010, with a cast led by Benedict Cumberbatch and Nancy Carroll. “I would go to a rehearsal room and direct it again in a moment,” she says. “It conveys a special poignancy, which is not only the impending return of global struggle, but also the fact that you have been too young to die for your country and are now considered too old – between and between, on the somehow at the wrong time and feeling redundant.”

What is striking is how often you get attempts at group portraits. Dodie Smith’s earlier hit Service (1932) was set in a department store facing a recession. In London Wall (1931), John van Druten touched on the tragicomedy of the secretaries and typists who toil at a law firm. Rodney Ackland’s Strange Orchestra (1932) brought bohos together in a boarding house.

The pressing question seems to be: what makes us – an ‘island race’, individuals at sea in an age of mass social organization – ‘us’? As the assembled relatives in Eliot’s The Family Reunion (1939) sing, “Why do we feel ashamed, impatient, whiny, ill at ease / Put together like amateur actors not assigned their roles?” It is an unease that resonates today.

There are clear points of artistic connection between some plays now approaching their centenary, and more recent efforts. Do we not sense the influence of The Family Reunion, with its troubled country house a shadowy symbol of England itself, in Alan Bennett’s People, a stately comedy with implications for the state of the nation? The impact of Priestley’s time shifts is palpable in Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia and Nick Payne’s Constellations. The satirical World War I musical Oh, What a Lovely War! owes something to Coward’s song-filled Cavalcade (1931), a morale-boosting epic that follows the fortunes of a family from the Victorian era to the Great War and beyond.

Despite appearances, 1930s drama was much more of an enduring cornerstone for postwar drama than a quaint dead end. And the most compelling reason to urgently reacquaint yourself with those bygone plays is the clear, chilling parallel of anxiety-ridden circumstances.

Dear Octopus is at the National’s Lyttelton Theater from February 7 to March 27; nationaltheatre.org.uk; Masquerade is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson