When is a masterpiece ‘by’ an old master, and when is it not? For example, could a Renaissance altarpiece remain unfinished over the centuries at the death of its maker, be completed by someone else, sawn into pieces and put back together again, with parts reconstructed from the beginning from preparatory drawings , and still ‘belong’ to the master? ?

You may not have heard of the 15th-century painter Francesco Pesellino – who is part of the National Gallery’s exhibition Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed. A pioneer of that opulent, bold, quattrocento Florentine style, and an influence on better-known figures such as Botticelli, Pesellino has been called “the Giorgione of Florence” – not only because of his impact on those who came after him, but also because he died to the plague just as his powers were beginning to peak (Pesellino was 35; the Venetian Giorgione also died in his thirties).

As with Giorgione, only a small number of Pesellino’s works have survived. But unlike Giorgione, what remains does not inspire great mystique. Giorgione’s portraits of noblemen seem to radiate to us the essence of the human condition from early modern Venice, while Pesellino was best known as an animal painter: his figures are beautifully posed, right down to the testicles on the horses, but they remain mainly symbols.

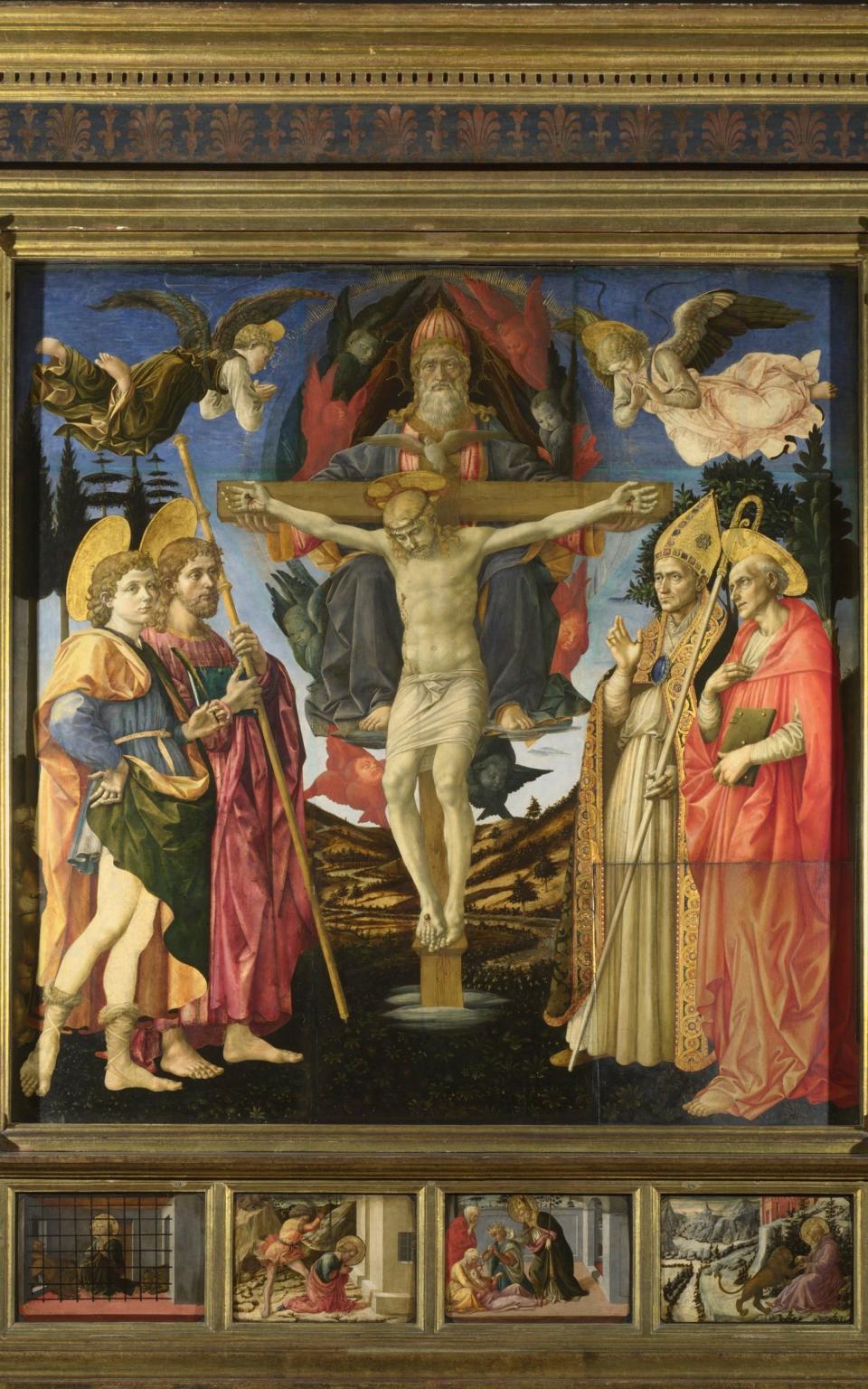

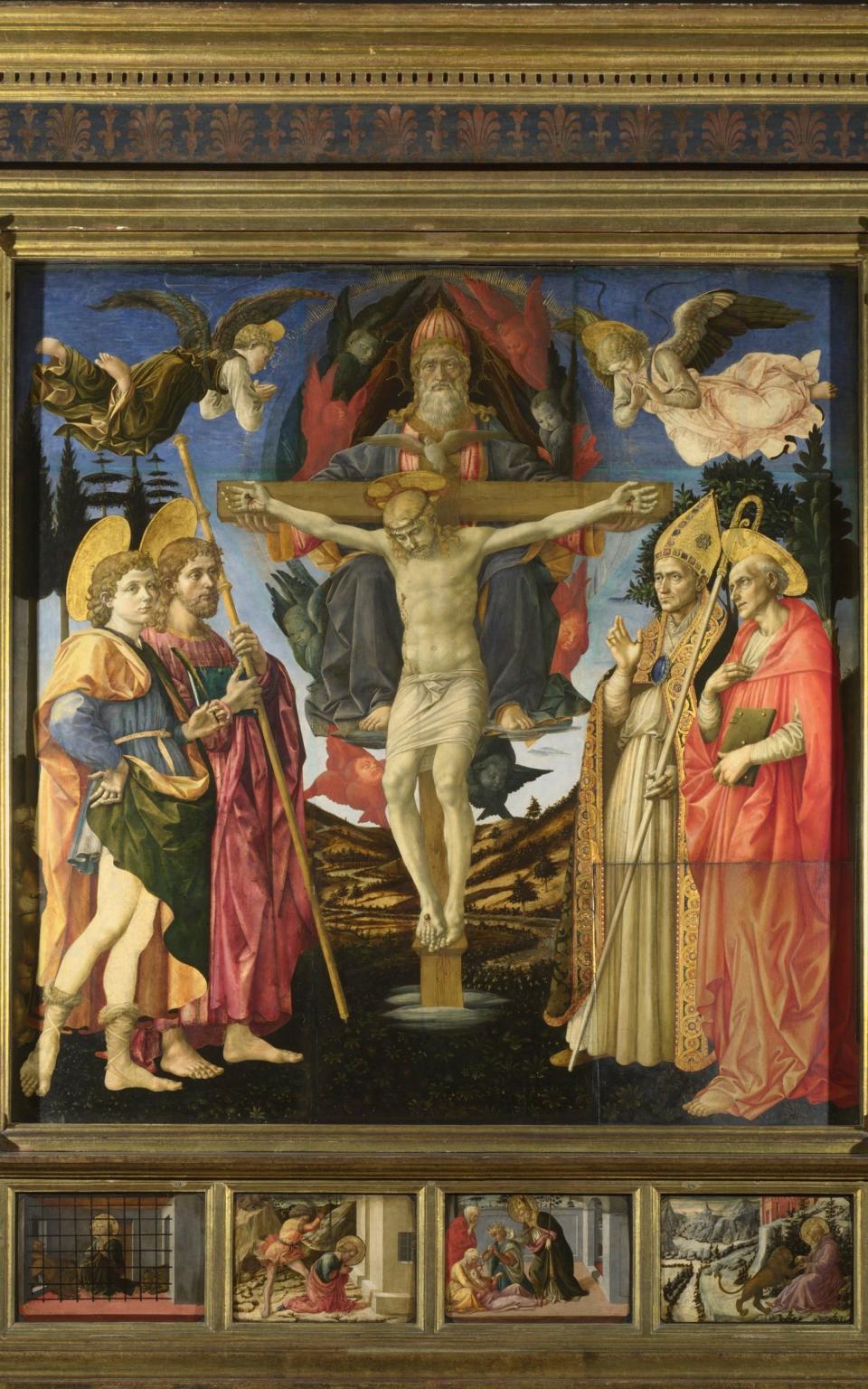

And while it may be difficult to authenticate a Giorgione, we can at least imagine that the works attributed to him in galleries bear the mark of an incomparable master. But it is an unavoidable fact that Pesellino’s altarpiece The Trinity with Saints – the centerpiece of the exhibition at the National Gallery – was cut into pieces and later reassembled with additions by restorers after it had been by another hand finished (Pesellino’s sometime teacher, Fra Filippo Lippi) when it remained incomplete at the time of Pesellino’s death in 1457.

Exactly how far the Trinity Altarpiece was completed when Pesellino died cannot be known with certainty – but we do know that the degree to which it was completed was important at the time. The altarpiece was commissioned in 1455 for a chapel in Pistoia, Tuscany, by priests with a budget of 200 florins, a considerable sum. After Pesellino died, his widow sued his former business partner for his pay cut, claiming that the altarpiece was largely completed; Lippi’s workshop, on the other hand, estimated it was only halfway there.

Today, Jill Dunkerton, curator of paintings at the National Gallery, has told me, we can get a good idea of the veracity of these competing claims by examining the main panel using infrared light, which reveals Pesellino’s signature: we see that the finished panel closely matches his plans. In contrast, the same method suggests that the panels on the predella – the lower layer of the altarpiece – were made almost entirely by Lippi’s workshop. In a sense, both Pesellino’s widow and Lippi’s workshop were right: Pesellino had indeed almost completed the altarpiece, if by the altarpiece you mean the main panel; but in terms of the work in general there was still about half to be done.

Lippi would have been an obvious candidate to complete the commission after Pesellino died: Pesellino had worked in Lippi’s workshop earlier in his career; they had worked on committees in the past. But Pesellino was a ‘control freak’, planning obsessively and working largely alone at this stage: one reason why his assignments tended to be slow.

Pesellino was also a remarkably logical painter, Dunkerton says. And if you look closely at the main panel, you can spot ‘illogical points’, or areas that haven’t quite been mapped out with the usual precision – hinting at Lippi’s involvement. For example, Christ on the cross has finely detailed hands, but God’s hands are a bit of a mess in comparison and give no sense of the weight of the cross.

Is the Trinity Altarpiece a lesser work because it does not bear the full sign of Pesellino? When I posed this question to Dunkerton, her response was immediate and emphatic: “No!” Lippi was a “much less logical” artist than Pesellino, she says. But you have to Real look for the “illogical details” to see them – and they were both “great” painters anyway. The altarpiece is also a testament to the student-teacher relationship that helped shape Florentine painting during this period.

This speaks about its historical significance. Pesellino was no Raphael. The Trinity Altarpiece is a beautiful work, but less important in itself from an art historical perspective than as a transition to something else – an “amazingly inventive and influential” work, according to Dunkerton, full of elements that would accompany Pesellino’s Florentine successors. The altarpiece belongs, or largely belongs, to the neglected master Pesellino. But it also belongs to a specific moment in Florentine art. Perhaps a city can also be an author.

There is a lesson in this when it comes to works that remained unfinished at the time of the creator’s death. There are two broad schools of thought – at least when it comes to publishing or exhibiting them (you could also just destroy them, or let them languish in some archive). The first is that the works should be released as they are, in whatever fragmentary state the late genius left them. The second is that they need to be tidied up and given some appearance of completeness, in accordance with what we can infer (for example from studying diary entries) as to what the artist’s likely intentions were.

In the first camp we have Max Brod publishing Kafka’s incomplete novels (famously against his late friend’s express instructions that Brod destroy them); and Robert Musil’s interminable modernist masterpiece The Man Without Qualities, whose published editions often include the author’s drafts, notes, and various false starts. In March 2024, an unfinished manuscript by Gabriel García Márquez – who died in 2014 – will be published as “the lost novel”, despite the author’s wish that the work will never see the light of day.

Meanwhile, in the second we have Beethoven’s once hypothetical 10th Symphony, composed in 1988 by Beethoven scholar Barry Cooper based on his study of the composer’s sketchbooks. And Jane Austen’s Sanditon, of which several ‘finished’ versions exist (including, most recently, a three-series TV drama adaptation by Andrew Davies). Perhaps we can also count in this category parts two and three of Marx’s Capital, which Engels completed after his death.

The first approach prioritizes fidelity to the authenticity of the artwork, unwilling to sacrifice it in the service of producing a recognisably ‘complete’ work. The second prioritizes creating a finished work and is willing to risk ignoring the author’s intentions to create such a work.

Any editor or successor must be guided by the condition in which he finds the unfinished work, as well as by its original purpose. And sometimes art for art’s sake can be beautiful, even if it’s unfinished. You can appreciate the imperfect charm of the 19th century portrait of an Austrian military officer, shown below. Or consider the version of Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, salvaged from fragments by Degas, which now hangs in the National Gallery. But the priests of 15th-century Pistoia would never have stood before an unfinished altarpiece. It makes sense to give an Austen romance a satisfying conclusion; but it seems like someone missed Kafka’s point if they tried to weave a traditional complete whole out of The Trial. Beethoven’s notes would never have resulted in a symphony without major intervention.

But it’s in them failure, rather than their success, to meet any predetermined standard of completeness in which the real value of such posthumous works lies. Whether completed, like Pesellino’s altarpiece, or left deliberately fragmented, such works remind us that (although the art market might argue otherwise, in its attempt to drive up increasingly obscene prices) each artwork is likely to be the product of multiple authors, or at least always open to intervention, whether from editors, conservators, translators, critics, or even readers. To quote a famous philosophical puzzle, Plutarch’s “Ship of Theseus” (if every plank is eventually replaced to prevent the ship from simply rotting away, is it still the ship of Theseus?), a ship can be more than have one shipbuilder.

The meaning of a work can change: art lives on through being appropriated, referenced, sampled and bastardized. Shakespeare’s greatness lies not just in how great his plays are, but also in the way they have shaped and continue to shape literature, popular culture, and language beyond. Or consider how the pedestrian fresco Ecce Homo (1930) by the painter Elías García Martínez for a church in Borja, Spain only became internationally known after it was accidentally transformed into the so-called ‘Monkey Christ’ by the eighty-year-old parishioner and unqualified restorer Cecilia Giménez ‘. ” in 2012.

Great works are not immediately and eternally great – the sole product of transcendent genius. Great works are the product of their time, in which many less brilliant people worked; individuals who were contemporaries of, who collaborated with, who inspired, informed or imitated those we recognize as “real” greats; who pushed things forward in their own way. Great works are important because of what we can do with them: how we can build on them today or transform them. This is surely the whole point of ‘rediscovering’ a painter like Pesellino. The beauty and brilliance of art lie in the promises it has not yet fully fulfilled.

Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed is on view at the National Gallery, London WC2 (nationalgallery.org.uk) from December 7 to March 10