Is or was there life on Mars? That profound question is so complex that it won’t be fully answered by the two NASA rovers now investigating it.

But because of the literal groundwork the rovers are doing, scientists are finally examining in depth and in unprecedented detail the evidence for life on the planet, known as its “biosignatures.” This search is remarkably complex and in the case of Mars it spans decades.

As a geologist, I have had the extraordinary opportunity to work on both the Curiosity and Perseverance rover missions. But no matter how much scientists learn from them, it will take another robotic mission to find out if Mars ever hosted life. That mission will bring rocks from Mars back to Earth for analysis. Then we will – hopefully – have an answer.

From habitable to uninhabitable

Although there is still so much mystery about Mars, there is one thing I am certain of. Among the thousands of photos taken by both rovers, I’m pretty sure no alien bears or meerkats will appear in them. Most scientists doubt that the surface of Mars, or its nearby surface, could currently support even single-celled organisms, much less complex life forms.

Instead, the rovers act as alien detectives, searching for clues that life existed centuries ago. That includes evidence of long-vanished liquid surface water, life-sustaining minerals and organic molecules. To find this evidence, Curiosity and Perseverance will take very different paths on Mars, more than 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) apart.

These two rovers will help scientists answer some big questions: Did life ever exist on Mars? Could it exist today, perhaps deep beneath the surface? And could it just involve microbial life, or is there a possibility that it is more complex?

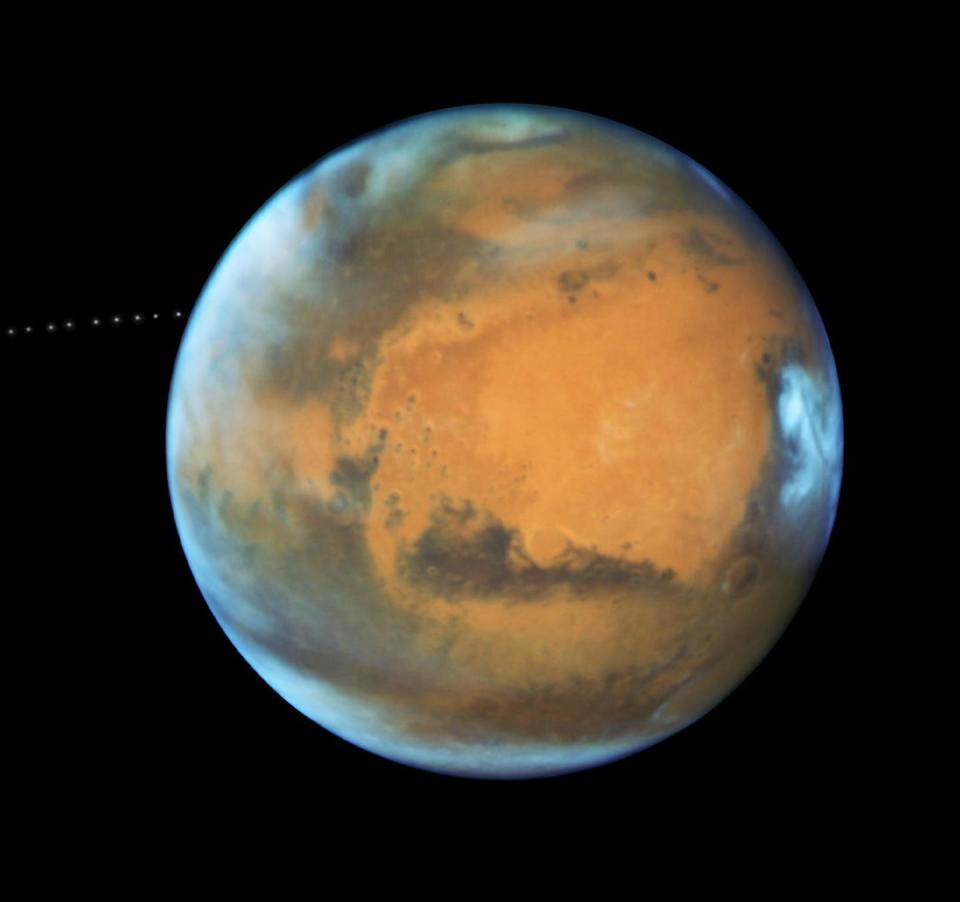

Today’s Mars is nothing like the Mars of several billion years ago. In its infancy, Mars was much more like Earth, with a thicker atmosphere, rivers, lakes, perhaps even oceans of water, and the essential elements necessary for life. But this period was cut short when Mars lost its magnetic field and almost all of its atmosphere – now only 1% as dense as Earth’s.

The change from habitable to uninhabitable took time, perhaps hundreds of millions of years; If life ever existed on Mars, it probably went extinct a few billion years ago. Gradually, Mars became the cold and dry desert it is today, with a landscape similar to the dry valleys of Antarctica, without glaciers and plant or animal life. The average temperature on Mars is minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 62 degrees Celsius), and its meager atmosphere is composed almost entirely of carbon dioxide.

Early exploration

Robotic exploration of the surface of Mars began in the 1970s, when life-detection experiments during the Viking missions failed to provide conclusive evidence for life.

Sojourner, the first rover, landed in 1997 and demonstrated that a moving robot could perform experiments. Spirit and Opportunity followed in 2004; both found evidence that liquid water once existed on the surface of Mars.

The Curiosity rover landed in 2012 and began its ascent of Mount Sharp, the 5,500-foot mountain in Gale Crater. There’s a reason NASA chose it as a research site: the mountain’s rock layers show a dramatic shift in climate, from a climate with abundant liquid water to the arid environment of today.

So far, Curiosity has found evidence at several sites of past liquid water, minerals that can provide chemical energy, and intriguingly, a variety of organic carbon molecules.

Although organic carbon itself is not living, it is a building block for all life as we know it. Does its presence mean that life once existed on Mars?

Not necessary. Organic carbon can be abiotic, that is, not related to a living organism. For example, perhaps the organic carbon comes from a meteorite that crashed on Mars. And while the rovers are carrying wonderfully sophisticated instruments, they can’t tell us definitively whether these organic molecules are linked to past life on Mars.

But laboratories here on Earth probably can. By collecting rock and soil samples from the surface of Mars and then returning them to Earth for detailed analysis with our state-of-the-art instruments, scientists can finally get the answer to an age-old question.

Perseverance

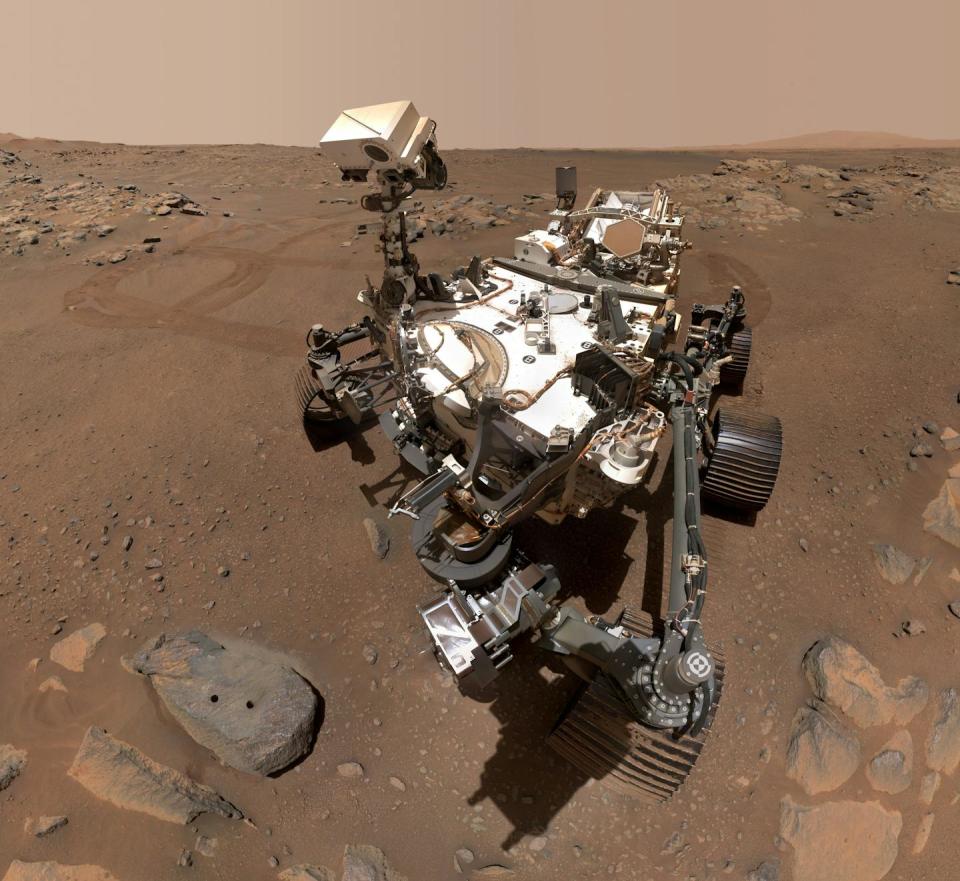

Meet Perseverance, NASA’s newest flagship mission to Mars. For the past three years — it landed in February 2021 — Perseverance has searched for signs of bygone microbial life in the rocks inside the Jezero crater, which was chosen as a landing site because it was once home to a large lake.

Perseverance is the first step of the Mars Sample Return mission, an international effort to collect rocks and soil on Mars for return to Earth.

The instrument suite aboard Perseverance will help the science team choose the rocks that seem to promise the most scientific returns. This will be a careful process; after all, there would only be 30 seats on the ride back to Earth for these geological monsters.

Budget problems

NASA’s original plan called for returning these samples to Earth by 2033. But work on the mission – now estimated to cost between $8 billion and $11 billion – has slowed due to budget cuts and layoffs. The cuts are serious; a request for $949 million to fund the mission for fiscal year 2024 was reduced to $300 million, although efforts are underway to restore at least some of the funding.

The Mars Sample Return mission is critical to better understanding the potential for life beyond Earth. The science and technology that make this possible are both new and expensive. But if NASA discovers that life once existed on Mars — even just by finding a microbe that’s been dead for a billion years — it will show scientists that life isn’t a one-time fluke that only happened on Earth. occurred, but a more general phenomenon that occurs on many planets.

That knowledge would revolutionize the way humans see ourselves and our place in the universe. This undertaking involves much more than just returning some stones.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Amy J. Williams, University of Florida

Read more:

Amy J. Williams is receiving funding from NASA Participating Scientist grants related to the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover and the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover.