What does the word nature mean to you? Does it conjure up visions of wild places far from the hustle and bustle of people, or does it also include people? The meaning of nature has changed since the word was first used as early as the 15th century.

Now a new campaign, We Are Nature, aims to convince dictionaries to include humans in their definitions of nature. A collaboration between a group of lawyers and a design firm, this campaign includes a petition and an open letter, as well as a collection of alternative definitions from various thinkers and authors (including myself). Here is my definition of nature:

The living world consists of the totality of organisms and the relationships between them. These organisms include bacteria, fungi, plants and animals (including humans). Some definitions may also include non-living entities as part of nature – such as mountains, waterfalls and cloud formations – in recognition of their important role as the basis for the web of life.

Derived from Latin Naturally, which literally means “birth,” nature used to refer only to the innate properties or essential nature of something. But over time it also came to describe something ‘other’, or something separate from humans. For example, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines nature as:

The phenomena of the physical world collectively; specifically, plants, animals, and other features and products of the Earth itself, as opposed to humans and human creations.

But how did we arrive at such a definition, which depends on being separate from, rather than part of, the natural world? Since the 17th century, a rationalist worldview, inspired by philosophers such as René Descartes, increasingly saw things from a mechanical perspective, likening the workings of the universe to a large machine. Rather than any form of divine spirit inhabiting the natural world, this perspective emphasizes the gap between the human spirit and physical matter.

Anything non-human fell into the latter category and was compared to clockwork machines. But this view has since been shown to lead to animal cruelty, and many environmental organizations, including the European Environment Agency, suggest this disconnect is accelerating the decline of nature.

Is it okay to change words in a dictionary through lobbying? There are two lines of thought here. You might say yes, if the scientific evidence suggests that the distinction between nature and humans is an illusion – something I have argued based on findings in biology, ecology and neuroscience.

A dictionary definition represents society’s way of mapping the natural world. This in turn influences our perception of our place in it – and the actions we take to protect nature. So the words we use have a real impact: they determine how we think and determine how we feel and act. Linguist George Lakoff has argued that they ultimately structure our society.

My children are growing up in a world where people feel disconnected from nature – in fact Britain is one of the most isolated countries. Research shows that this leads to people making fewer positive environmental changes in their behavior, such as reducing their carbon footprint, recycling or doing voluntary conservation work.

Conversely, when people feel enmeshed in nature, they are not only greener in their behavior, but they also tend to be happier. So I definitely want my children to grow up feeling like they are part of nature.

There are some words that I definitely recommend we use less. I don’t like the term ‘natural capital’, which refers to nature as an asset that can be commodified and sold. These words have a place among professional environmentalists and policy makers, but they can also create psychological distance and make us care less about nature.

A sustainability-focused communications agency discovered that the best way to motivate people about protecting nature is through messages based on awe and wonder, rather than the economic value of nature. Scientific studies support this.

Dangers of mastering language

But I’m torn. Another line of thought suggests that it is not okay to change the meaning of words through lobbying, and that dictionaries should reflect how words are used – the OED takes this position.

Dystopian fiction, including George Orwell’s 1984, highlights the dangers of a world where mastering language allows control over the population. Dictionaries that bow to lobbying pressure appear to be setting a dangerous precedent.

As for the meaning of nature, if a word is too broad, it can lose its usefulness in communication, just as a dull knife is a poor tool for cutting food. People who want to express the natural world can simply use other words, such as “environment.” This word is derived from French environmentexplicitly describing something around us.

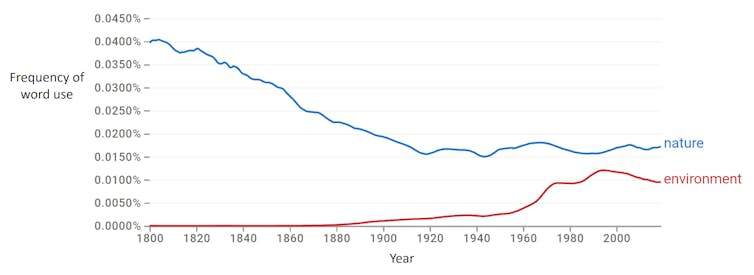

In our modern lexicon, the environment has already replaced nature. This may reflect a subtle cognitive shift where people are increasingly seen as separate entities, separate from the natural world.

Nature versus environment: tracking the use of these words

But the We Are Nature campaign doesn’t just lobby the OED based on preferred language. The organizers have collected many historical uses of the word nature from 1850 to the present, some of which include people, and presented this evidence to the dictionary. As a result, in April 2024 the OED removed the “obsolete” label from a secondary, broader definition of nature that included “the entire natural world, including humans.”

But to change the primary definition of nature from “unlike humans” to “including humans” will require more people to use the word in a way that reflects how humans are intertwined with the entire web of life.

The great thing is that by doing this we rekindle the bonds of care for the living world around us. And by dispelling the illusion of our separation from nature, we can also expect to live happier lives. Words matter – there is restoration and joy in talking about how we are nature.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tom Oliver has received research funding from BBSRC, NERC and Natural England to quantify the impacts of climate change on biodiversity and develop climate adaptation plans for people and other species. He was associated with Defra as a senior scientific fellow on their Systems Research Programme, with the Government Office for Science looking at long-term risks to Britain, and spent four years at the European Environment Agency on their scientific committee. He is a member of the Scientific Board of the Food Standards Agency and of the Expert College Office for Environmental Protection. He is the author of The Self Delusion: The Surprising Science of Our Connection To Each Other and the Natural World, published by Weidenfeld and Nicholson.