Here’s a plan for a day out on the Metropolitan line of the London Underground, although we won’t be underground at any time and will be traveling 25 miles from London. But first a little history.

In 1863 the Metropolitan Railway (Met) built the first underground railway line – from Paddington to Farringdon. Five years later the Met, an ambitious and restless group, added an above-ground northern branch, from Baker Street to St John’s Wood, in the hope of conquering the commuter market. As this cog, then known as the Extension Line – and still so called by an endearingly affected friend of mine – split and stretched into Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire, the Met built adjacent houses in the nostalgic Tudorbethan style. Between 1915 and 1933 (when the Met suffered the indignity of becoming merely a ‘line’ of the London Underground), these were marketed as Metro land.

Fifty years ago, John Betjeman (JB) – recently named Poet Laureate – wrote and presented a BBC documentary called Metro-land – and yes, it is on both YouTube and DVD. In his biography of Betjeman, AN Wilson called it “a great television poem”, with the script partly simplified and the whole very lyrical. The producer, Eddie Mirzoeff, recalls: “When it came together in the editing room, it became something exciting. I knew John liked it because he started bringing his friends to see it.

What follows is partly a replay of the journey JB takes in the film, partly an itinerary for visiting the nicer Metro country spots along the main section of the Extension Line.

We start at Baker Street, the unofficial headquarters of Metro-land. Above the station is a 1920s block built by the Met, Chiltern Court, which has been home to famous railway enthusiasts including HG Wells and the quizmaster Hughie Green, who had a large model railway in his flat. Chiltern Court once had a restaurant and JB starts there, thinking about how Metroland women, “from Pinner and Ruislip, after a day’s shopping at Liberty’s or Whiteley’s”, would have tea at Chiltern Court before driving home via the Extension. Scenes unfold around JB that are almost as grand as he spoke in 1973. That restaurant is now the Metropolitan Bar, a Wetherspoon’s pub that opens at 8am (9am on Sundays), which is either very civilized or very uncivilized. A definite plus is that it is packed with Met Railway memorabilia.

The camera follows Oakington Avenue as Betjeman chants house names: ‘Rusholme, Rustles… Rose Hatch, Rose Hill, Rose Lea…’

We can ignore the first section of the Extension Line, which continued to be rationalized to get trains out of London faster. For example, the stations between Finchley Road and Wembley Park are now served by the Jubilee Line. We might get off at Wembley Park to look at some of the houses in Metroland. In the documentary, the camera follows along Oakington Avenue as Betjeman chants house names: “Rusholme, Rustles… Rose Hatch, Rose Hill, Rose Lea…” Each “slightly different from the next” and built on fields that once “flourished of the buttercups”. ”. There’s a certain acidity here. Although JB had a fondness for Metro country, he is haunted by the “mild homeland acres” that were destroyed to make way for this land.

Related: Steam and sparkle: 6 of the best Christmas train journeys in Britain

Our train, by the way, is one of the S8 trains, built specifically for the Extension run, with some transverse seating (sideways against the window), to mirror the compartments of the old Met cars. After passing the Metro estate at Northwick Park, we disembark at Harrow-on-the-Hill.

At the adjacent bus station we board line 258 to Watford. As the bus travels along Station Road, the half-timbered facades above the modern shop fronts reveal Metroland’s origins. Gradually the houses become thinner; they are also expanding and becoming what the Metro-land brochures call “homesteads.”

After about 15 minutes we alight at leafy Clamp Hill and turn left past Old Redding, with Harrow Weald woodland on either side. Harrow Weald, one of the larger green spaces to survive development, was something of a hole in the middle of Metro-land. On the right we enter the wooded grounds of Grim’s Dyke, which today (and when JB visited) is a hotel. Grim’s Dyke was built as a private house in 1872 by Norman Shaw. “I’ve always thought of it as a prototype of all the suburban houses in southern England,” says JB, marveling at its diverse facades. It also seems like the prototypical Metro mansion.

During his visit, Betjeman met the apparently all-female Byron Luncheon Club in a conference room (Byron attended Harrow School). I sat in the cozy bar – the woods misty behind the stained glass windows – next to a man trying to sell an AI app to a businesswoman. He kept saying things like, “Let’s ask the bot the question, okay? I really have no idea what it says!”

As we drive further north – across the most rural part of the Extension – we come to Chorleywood, a harmonious collection of cottage-like Metro country houses

The menu featured grilled halloumi and Bombay street food, but I thought pumpkin soup and a cheese sandwich were more in keeping with Metro-land. After lunch I wandered into the misty woods in search of what JB calls the “gloomy pool” where in 1911 the librettist WS Gilbert – owner of Grim’s Dyke – died saving a young woman from drowning. So Gilbert never saw what JB calls “the rising tide of Metroland.” If he had, it might have been a good subject for one of his (and Sullivan’s) satirical operettas.

After driving the 258 back to Harrow-on-the-Hill, we continue north on the Extension, to Moor Park station. This serves the Moor Park Estate, described in a 1925 Metro-land brochure as “perfect modern houses in a fine old half-timbered park”. I once walked through Beverly Hills until I was turned away by an LAPD officer (“No one walks here, buddy”), and Moor Park is the closest I’ve seen to Britain. The documentary shows a commissioner at a traffic barrier being sycophantic with a resident before brusquely ordering a stranger to go back where she came from. Nowadays the barriers go up automatically, but your license plate is photographed and the ‘access only’ rule applies. But everyone can walk through the streets of gigantic white villas, silent, except for the occasional Porsche that does twice the 20mph speed limit.

Moor Park is also the name of the adjacent golf club, and a public footpath crosses the course (search for Moor Park on shareyourroute.com). As far as a golf course can be beautiful, Moor Park is, partly because buggies are not allowed. The path provides views of the Neo-Palladian mansion that stands ghostly next to the fairways and is now Moor Park’s clubhouse. JB penetrates the beautiful interior, which regular footpaths are not allowed to do. As he examines the painted gods, he says: “What Georgian has heard with these classical gods / who should now listen to the golfer’s story…”

There are six golf courses within walking distance of Moor Park. They – and many others – were depicted on Metro maps as little red flags. Stations and roads were also highlighted, which the Met deemed not a threat, believing that cars would only be used for leisure and not for commuting.

Moving further north – across the most rural part of the Extension – we come to Chorleywood, a harmonious cluster of cottage-like Metro country houses, mainly to the west of the station; to the east is the 80-hectare Common, which is both surprisingly wild and equipped with walking trails. JB loved Chorleywood: “A lot of effort has been made to maintain the quality of the land here.” In 2004, a study by the University of Oxford named Chorleywood the happiest place in Britain. I thought about this as I joined the crowd of commuters holding their contactless cards waiting to tap out of the station – a slow process as everyone said, “After you,” “No, after you.”

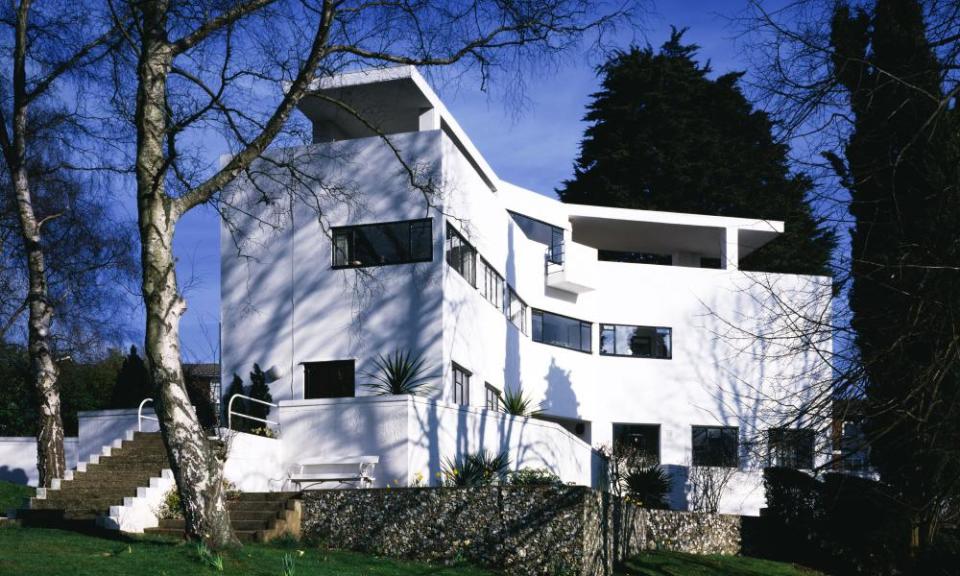

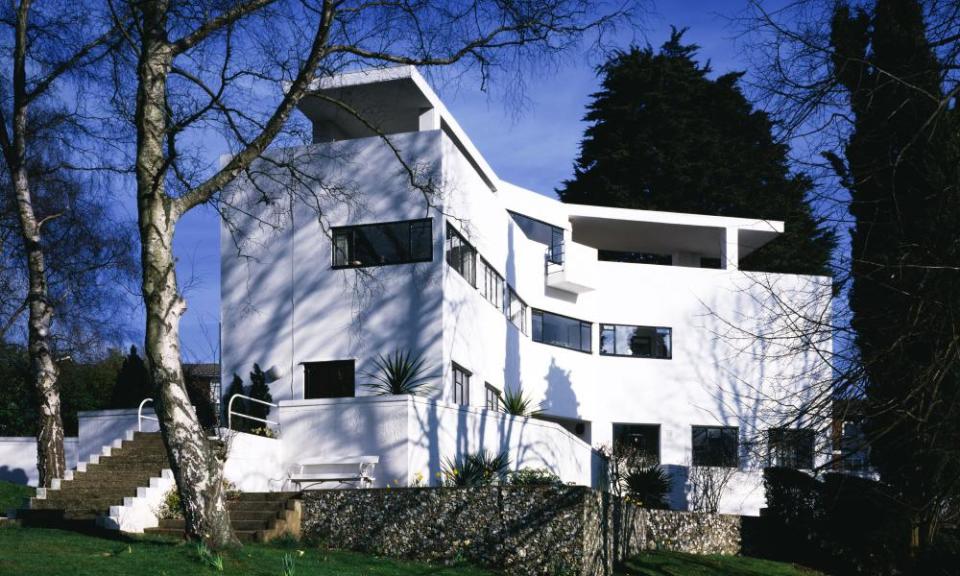

On to Amersham, whose Metro mansions surround the station, but Old Amersham High Street is the draw, with its select shops and stooped pubs, and this requires a 15-minute stroll down another Station Road. When JB came this way, he stopped to look at “a concrete house in the shape of a letter Y.” This – just off Station Road – is High and Over, a stern modernist statement from 1931, and perhaps a rebuke to the pleasant farmhouses in the area. On the slope below are a few smaller modernist houses, as if to provide moral support.

In Old Amersham, I dined on fancy fish and chips at the 15th-century Kings Arms, whose exterior is so warped it looks like a reflection of itself in water. This is, perhaps even more than Grim’s Dyke, the true prototype of Metro country houses.

Afterwards there was nothing to do but return to the city (and a £3 glass of wine in those Baker Street ‘Spoons’) as Amersham is the end point. Beyond that, JB notes, “Grass triumphs. And I have to say I’m quite happy with it.”

Andrew Martin is the author of Death on a Branch Line (Faber & Faber, £9.99). To support The Guardian and Observer, order your copy at Guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply