In a week of national security focus in Washington, the White House confirmed Thursday that it had evidence that Russia was developing a space-based anti-satellite nuclear weapon.

National Security Council spokesman John Kirby told reporters that the White House believes the Russian program is “troubling” despite “no immediate threat to anyone’s security.”

The problem is that, depending on what kind of weapon this is, the consequences of using it can be indiscriminate: everyone’s satellites are threatened and the vital services that come from space infrastructure are broken.

The White House revelations come after House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Turner urged the administration late Wednesday to release information about what he called a “serious threat to national security.” There were then several days of comments and speculation about Russia either being prepared to launch a nuclear weapon into space or deploying an anti-satellite weapon powered by nuclear energy.

Kirby did not fully outline the nature of the threat, but he added that officials believed the weapon system was not an “active capability” and had not been deployed. To reassure listeners, Kirby said the weapon could not be used to cause physical destruction on Earth, but that the White House was monitoring Russian activities and would continue to take it “very seriously.”

During a visit to Albania on Thursday, Secretary of State Antony Blinken confirmed the news and stated that he expected to have more to say soon, adding that the Biden administration was “also consulting with allies and partners on the issue.”

While discussing the issue with Indian Foreign Minister Jaishankar and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Munich Security Conference, Blinken is said to have “emphasized that pursuing this capability should be a matter of concern.”

Denials from Russia

Moscow immediately denied the existence of such a program, stating it was a “malicious fabrication” created by the Biden administration to pressure Congress to pass the $97 billion (£77 billion) foreign aid bill approval, of which 60 billion dollars was intended for Ukraine. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters: “It is clear that the White House, through a con, is trying to encourage Congress to vote on a bill to allocate money; this is clear”.

At a press conference on the death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, Joe Biden declared that there was “no nuclear threat to the people of America or anywhere else in the world with what Russia is doing right now.”

The president added that there is “no evidence that they have made a decision to proceed with anything in space.” If Moscow decided to go ahead with the program, it would violate the Outer Space Treaty signed by 130 countries, including Russia.

The treaty bans “nuclear weapons or other types of weapons of mass destruction” in orbit, or the stationing of weapons in space “by any other means.” Anti-satellite weapons are nothing new. China launched a weapon to destroy a non-operational weather satellite in January 2007.

While the temptation to launch a nuclear strike into space may seem attractive to countries looking to challenge US dominance in this area, such actions come with great risk. It is not necessarily the destruction of objects in space from Earth that should be the primary concern when it comes to anti-satellite weapons in general, but the effect they have in space.

Mass of rubble

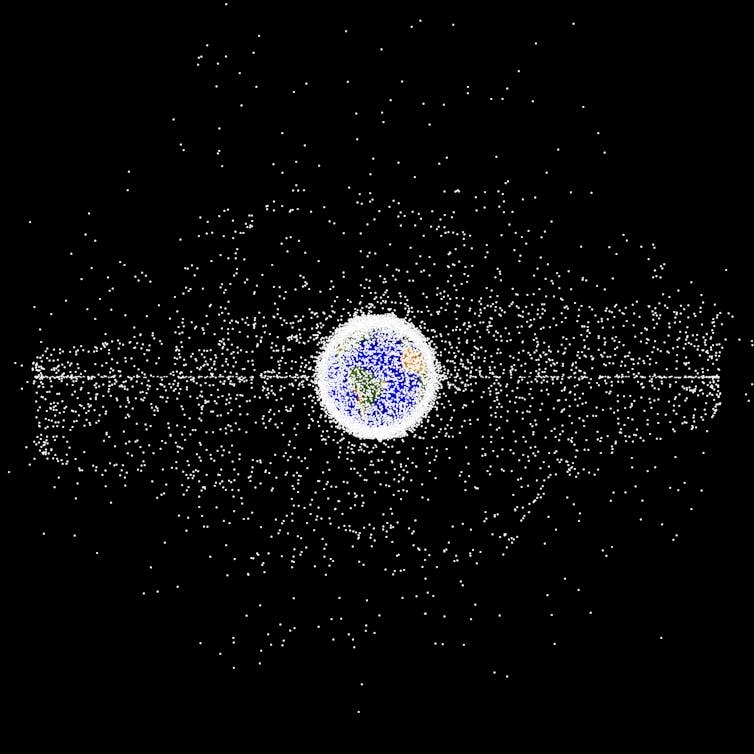

The destruction of a celestial body creates a mass of debris that varies in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. There are currently hundreds of millions of tracked pieces of space debris orbiting Earth.

The speed at which this space debris travels makes it a major hazard to other satellites and entities in space, such as the International Space Station (ISS), which must change course to avoid collisions that could cause widespread damage. The ISS has had to change course 32 times since 1999.

Once space debris is created, it is nearly impossible to control its post-impact trajectory or the orbital pattern it will follow around Earth. This could put a country’s space assets – such as satellites – at the same risk of destruction as those of an adversary. This situation has been described in terms similar to those of nuclear weapons on Earth, in terms of mutually assured destruction.

If a nuclear attack were carried out by a country in space with the intention of destroying satellites and also to demonstrate both the ability and willingness to use nuclear weapons in general, it would be virtually impossible to predict the consequences of such control action.

It would be quite certain that such an attack would have the intended effect of reducing an opponent’s space capabilities. For example, an attack on US assets could disable the satellite-based Global Positioning System (GPS) that Western countries rely on.

However, there is a very real possibility that it would also destroy the space assets of the country behind the attack, as well as that same country’s allies and friends. This could lead to increased tensions and loss of support from that country.

The inability to control the effects of attacks in space, whether they originate from a weapon in space or on Earth, makes such actions the subject of a great deal of consideration and debate in all countries active in the space domain.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The authors do not work for, consult with, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.