With the new Amy Winehouse biopic ‘Back to Black’, which will be shown in American theaters from May 17, 2024, the late singer’s relationship with alcohol and drugs is being reexamined. In July 2011, Winehouse was found dead in her north London flat at the age of 27 after ‘death by misadventure’. That is the official British term used for accidental death caused by a voluntary risk.

Her blood alcohol concentration was 0.416%, more than five times the legal limit for intoxication in the US – causing her cause of death to be later amended to include “alcohol toxicity” after a second inquest.

Almost thirteen years later, alcohol consumption and binge drinking remain a major public health crisis not only in the UK but also in the US.

About 1 in 5 adults in the US report binge drinking at least once a week, with an average of seven drinks per binge episode. This is well in excess of the amount of alcohol thought to cause legal intoxication, usually defined as a blood alcohol concentration of more than 0.08% – an average of four drinks in two hours for women, five drinks in two hours for men.

Among women, the number of days of ‘heavy drinking’ has increased by 41% during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to pre-pandemic levels, and adult women in their 30s and 40s are rapidly increasing their rates of binge drinking, with no evidence that these trends are slowing down. . Despite efforts to understand the general biology of substance use disorders, scientists and physicians’ understanding of the relationship between women’s health and binge drinking has lagged.

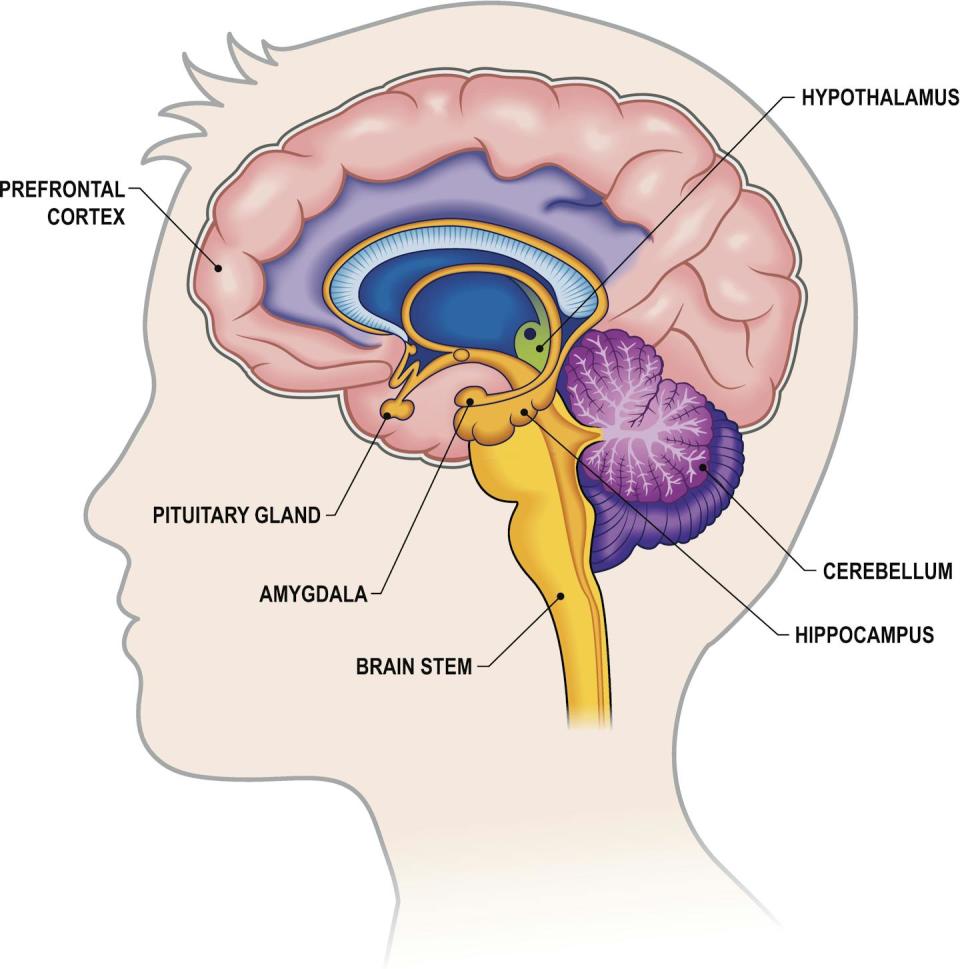

I am a neurobiologist focused on understanding the chemicals and brain regions underlying alcohol addiction. I study how neuropeptides – unique signaling molecules in the prefrontal cortex, one of the most important brain areas for decision-making, risk-taking and reward – are changed by repeated exposure to excessive alcohol consumption in animal models.

My lab focuses on understanding how things like alcohol alter these brain systems before diagnosable addiction occurs so that we can better inform efforts for both prevention and treatment.

The biology of addiction

Although problematic alcohol use has likely occurred as long as alcohol has existed, it wasn’t until 2011 that the American Society of Addiction Medicine recognized substance addiction as a brain disease—the same year as Winehouse’s death. The diagnosis of alcohol use disorder is now used in place of outdated terms, such as labeling an individual as an alcoholic or having alcoholism.

Researchers and doctors have made great strides in understanding how and why drugs – including alcohol, a drug – change the brain. Often people consume a drug like alcohol for the rewarding and positive feelings it provides, such as enjoying a drink with friends or celebrating a milestone with a loved one. But what starts as controlled alcohol consumption can quickly turn into cycles of excessive alcohol consumption, followed by withdrawal symptoms.

While all forms of alcohol consumption carry health risks, binge drinking appears particularly dangerous because of the way that repeatedly switching between a high state and a withdrawal state affects the brain. For example, for some people, alcohol consumption can lead to “hangxiety,” the feeling of anxiety that can accompany a hangover.

Repeated episodes of binge drinking and drunkenness, combined with withdrawal symptoms, can spiral, leading to relapse and alcohol reuse. In other words, alcohol consumption shifts from a reward to an attempt to avoid feeling bad.

It is logical. With repeated alcohol use over time, the brain areas involved with alcohol can shift from those traditionally associated with drug use and reward or pleasure, to areas of the brain typically involved with stress and anxiety.

All these stages of drinking, from enjoying alcohol to withdrawal to the cycles of craving, are constantly changing the brain and its communication pathways. Alcohol can affect several dozen neurotransmitters and receptors, complicating understanding its mechanism of action in the brain.

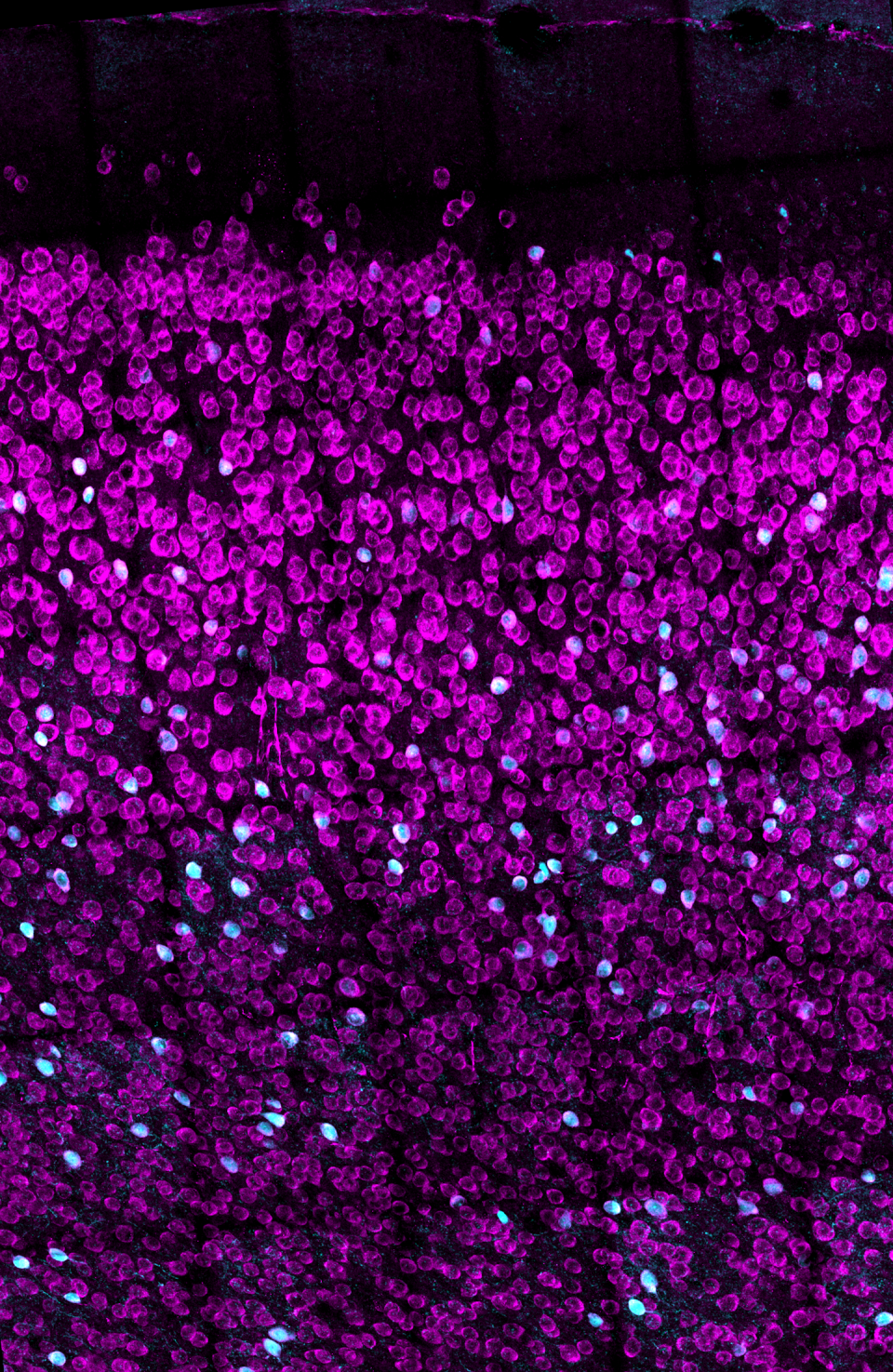

The work in my lab focuses on understanding how alcohol consumption changes the way neurons in the prefrontal cortex communicate with each other. Neurons are the brain’s main communicator, sending both electrical and chemical signals to the brain and to the rest of your body.

What we’ve found in animal models of binge drinking is that certain subtypes of neurons lose the ability to talk to each other properly. In some cases, binge drinking can permanently reshape the brain. Even after a prolonged period of abstinence, the conversations between the neurons do not return to normal.

These changes in the brain can occur before noticeable changes in behavior occur. This could mean that the neurobiological basis of addiction can take root long before an individual or their loved ones suspect an alcohol problem.

Researchers like us don’t yet fully understand why some people are more sensitive to this shift, but it likely has to do with genetic and biological factors, as well as the patterns and circumstances under which alcohol is consumed.

Women are forgotten

As researchers continue to understand the welter of biological factors underlying addiction, there is one population that has been largely overlooked: women.

Women may be more likely than men to experience some of the most catastrophic health effects caused by alcohol consumption, such as liver problems, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Middle-aged women are now at the highest risk for binge drinking compared to other population groups.

When women consume even moderate amounts of alcohol, their risk of several cancers increases, including digestive, breast and pancreatic cancer, among other health problems – and even death. Thus, the worsening rates of alcohol use disorders in women necessitate the need for a greater focus on women in research and the search for treatments.

Yet women have long been underrepresented in biomedical research.

It wasn’t until 1993 that clinical research funded by the National Institutes of Health was required to include women as test subjects. In fact, until 2016, the NIH didn’t even require sex to be considered as a biological variable by federally funded researchers. When women are excluded from biomedical research, doctors and researchers are left with an incomplete understanding of health and disease, including alcohol addiction.

There is also increasing evidence that addictive substances can interact with sex hormones such as estrogen and progesterone. For example, research has shown that when estrogen levels are high, such as before ovulation, alcohol may be more satisfying, which could lead to more binge drinking. Currently, researchers do not know the full extent of the interaction between these natural biological rhythms or other unique biological factors involved in women’s health and propensity for alcohol addiction.

Looking forward

Researchers and lawmakers recognize the vital need for more research into women’s health. Major federal investments in women’s health research are a critical step toward developing better prevention and treatment options for women.

While women like Amy Winehouse may have been forced to struggle with substance use disorders and alcohol both privately and publicly, the increasing focus of research on addiction to alcohol and other substances as a brain disorder will open up new treatment options for those who suffer its consequences.

Visit the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to learn more about alcohol use disorders, causes, prevention and treatments.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Nikki Crowley, Penn State

Read more:

Nikki Crowley receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences endowment funds.