University leaders pay close attention to comparative rankings such as those offered by Times Higher Education, ShanghaiRanking Consultancy and others. Rankings influence student enrollment, attract talented faculty, and justify donations from wealthy donors. University leaders oppose them, and some schools “pull out,” but rankings have an impact.

A radical shift in the data underlying the rankings is about to turn the world of rankings upside down – largely in favor of China’s position.

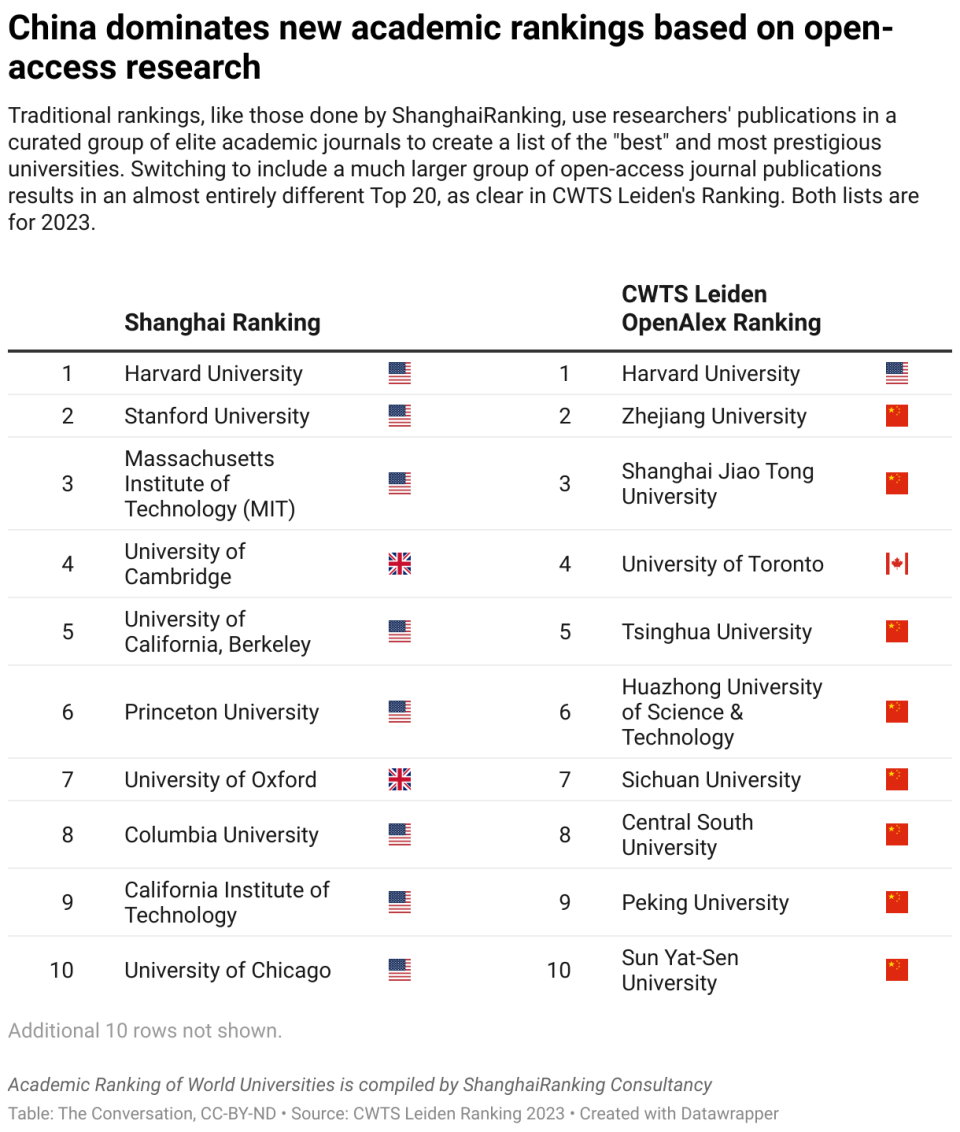

For example, in early 2024, the CWTS group of the Leiden University Center for Science and Technology Studies released new university rankings that add open data sources to the traditionally compiled list of elite journals that had been the standard. The results show that the world is turning upside down for university rankings.

Where once the list of universities with the highest scientific impact would have been Oxford, Stanford, Harvard and MIT, the new top 10 universities with high scientific impact include eight universities from China. Only Harvard and the University of Toronto maintain a top 10 position.

What does this transformation mean for understanding scientific excellence? I study the global research system and its contribution to social welfare. China’s rapid progress in science and technology, driven by investment in research and university strength, has alarmed the United States and other countries. Concerns are growing that the US could lose its competitive advantage to an assertive rival, with potential consequences for national security, economic status and global influence. These new rankings are likely to cause even more alarm.

Wider reach from more sources

The ranking programs rely heavily on quantitative assessments called “indicators.” A look at the influential ShanghaiRanking criteria shows that the input for the rating includes “articles indexed in the major citation indexes.” The popular indices come from a highly curated set of scientific journals such as Cell, The Lancet and Chemical Reviews. The most reputable index that compiles information about these and other journals is Web of Science’s Science Citation Index or SCI, a product of careful standardization and data enrichment by Clarivate.

However, SCI represents only a fraction of the work published worldwide. Among other criticisms, many people criticize the SCI’s exclusivity and perceived Western bias.

But careful management makes it the gold standard for academic indexing and one that journals and authors are eager to adhere to. Its value lies in its reproducibility: it is possible to dive into it multiple times using different search strategies and produce similar results.

The dependency on managed databases is about to end with the introduction of rankings based on open data such as that collected by OpenAlex. OpenAlex claims to include more than 100,000 journals – of widely varying quality and editorial practices – compared to SCI’s 9,200. All data in OpenAlex has been released into the public domain with the laudable goal of making research freely available to everyone. The downside is that this broader network penetrates predatory journals that exploit researchers and undermine the quality and integrity of scholarly communication.

A reflection of Chinese research productivity

The volume of scientific articles appearing in the open databases has a major impact on China’s position in the open source rankings. Chinese scholars produce a vast amount of written work, some in English, some in Chinese; estimates of percentage shares for language vary widely, but hover around 50-50. As China has invested in education and increased its scientific and technical capacity, more and more people are coming out with scientific articles.

From a very small number in the 1980s, China had 2.2 million scientists and engineers in 2023, based on UNESCO data. China’s scientific production of scientific and technical articles has shown a very rapid increase since the 1990s, with growth outpacing all other countries. Quality has lagged behind quantity, but China surpasses the United States in the total number of scientific publications in the Web of Science, in my opinion – a shift in leadership not seen since the US overtook Britain in 1948.

Although the figures are dated, when I counted Chinese scientific publications in 2010, my colleague and I estimated that between 2000 and 2009, China published about 1 million scientific articles that were not collected by the Web of Science. This means that they did not “count” towards the traditional rankings. These publications are counted in the new open databases. Many of the articles in open source or open access journals will not be considered of high quality; nevertheless, they become part of the written record.

Open access publishing services have grown rapidly and offer fast publication times, but there are questions about the quality of their journals. Open publishing services such as MDPI and Frontiers have an inordinately large number of Chinese contributors compared to those from other countries.

The open access services often include content from potential paper mills, companies that produce so-called scientific manuscripts for sale. Despite concerns about the reputation and editorial practices of these publishers and editors, there is little oversight. These services flood the publishing industry with large numbers of lower-quality articles.

Chinese researchers and their sponsoring institutions place enormous value on publishing in international journals, even those from questionable publishers. Citation stacking practices – where authors cite the work of compatriots to improve their citation profiles – skew counts to boost China’s performance.

China is trying to crack down on malicious practices. To its credit, the Chinese government recently announced the retraction of 17,000 articles with a Chinese author or co-author. Efforts are underway to improve quality. Government payments to researchers for articles in ranked journals will be halted.

Despite the quality questions, the numbers alone will push China up the rankings. This rapid shift will strengthen China’s position relative to the rest of the world. In itself, the increase does not reflect a change in quality, status or output, but it will continue to fan the flames of those alarmed by China’s rise in global science, technology and innovation circles, and perhaps further question the rankings.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Caroline Wagner, The Ohio State University

Read more:

Caroline Wagner does not work for, consult with, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.