It is impossible to discuss the character and evolution of modern British theater without referring to Edward Bond. More than any other playwright of his generation – those who grew up during the war – he was drawn to violence.

“I write about violence as naturally as Jane Austen wrote about manners,” he once declared. The play that made a name for itself at home and abroad – Saved (1965) – contains one of the most famous scenes from post-war drama. In it, a group of young working-class men abuse and stone (in a simulated but gruesome manner) an invisible baby in his pram, one of his own father’s culprits.

Like John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, which premiered at the Royal Court in 1956, it caused national shockwaves and ushered in a generation prepared to confront contemporary life with an explicitness that had hitherto been lacking. The theatrically alluring rhetoric that was characteristic of Osborne’s work or that of Pinter had also disappeared. The explosion of visceral drama in the 1990s – especially the work of Sarah Kane – is difficult to imagine without his example.

The outrage over Saved (1965) and Early Morning (1968) even brought the issue of centuries-old theater censorship to a head. Laurence Olivier himself took the stand in Saved’s defense after the Lord Chamberlain’s office urged a prosecution at the Royal Court, on the grounds that the piece had not been approved for presentation. So many people tried to attend the trial that the author himself was denied entry. The theater lost that particular battle, but the debate was sparked in parliament and a bill was being drafted to take theaters out of state control. Then the blatantly irreverent Early Morning – which revealed, among other things, that Queen Victoria was in love with Florence Nightingale and cannibalistically gorged herself – was refused a license.

That was the first outright ban on a play – removing the loophole of a “club” performance (members only) – in the 20th century. The show went ahead through an attended dress rehearsal – an insult to the authorities, but one that did not provoke prosecution. When the Theater Act of 1968 was passed, the tide had turned.

Enduring gratitude is therefore owed to Bond. And that was just the beginning of a career in which he wrote until the mid-2010s (he wrote more than 50 plays). Yet it is entirely possible that you have been an avid theatergoer for the past thirty years and have barely seen any of his work – a testament to his increasingly isolated position, revered but existing almost in a vacuum.

That a playwright should have been regarded as one of the most important and influential of his time and yet has been so sidelined is one of the most glaring anomalies of British theatre. It could be argued that after helping to dismantle state censorship, he then dismantled his own professional career. He competed against the most important new writing theaters of the subsidized sector. The RSC launched his apocalyptic trilogy The War Plays (1985), but after leaving rehearsals, as director he criticized the production and the setting.

“The men who run the National and the RSC – I call them the floating dead,” he railed. He hated the Royal Court’s 1984 revival of Saved (directed by Danny Boyle); then-artistic director Max Stafford-Clark described him as “the most difficult person I have worked with”. Turning his back on the main subsidized stages, Bond’s new work in the 21st century could often be found in Birmingham, performed by a theatre-in-education company called Big Brum, or abroad, particularly in France.

He always felt that the theater had failed him. He told me in 2011: “They’ve lost the Lord Chamberlain, but they’ve also lost me.” We met during rehearsals for the first London revival of Saved in almost 30 years (at the Lyric, Hammersmith). It was a production that reaffirmed the visceral impact of that stoning scene, but also the cruelty that lurks in low-level domestic exchanges – as original director Bill Gaskill noted, perhaps the most disturbing scene of all is the one in which the the baby’s cries at home go unnoticed for a small eternity.

Bond saw a continuum between the violence practiced in wartime and the inherently violent functioning of society in peacetime. People, he claimed, were not naturally aggressive or cruel, but became so through the social structures they inherited; it was the drama’s job to show us that uncomfortable fact. And by extension, most theater recoiled from it.

Bond’s bracing theoretical writings and grenades of aphorisms (“What is called the end of history is in reality the disappearance of the future”) usefully survive; they testify to the integrity in his work, but they also explain an ideological streak that caused him to see all social relations in the same dreary light. His later plays invited audiences to dine on horrors: Coffee (written in 1995) was inspired by the wartime mass murders of Jews by the Einsatzgruppen in the Babi Yar ravine. At The Inland Sea (1996), concentration camp victims entered the bedroom of a schoolboy immersed in history. His last play, Dea, a reference to Medea – performed off the beaten track, in Sutton, in 2016, was a litany of rape and bloody brutality – so much so that, to some, it seemed like self-parody.

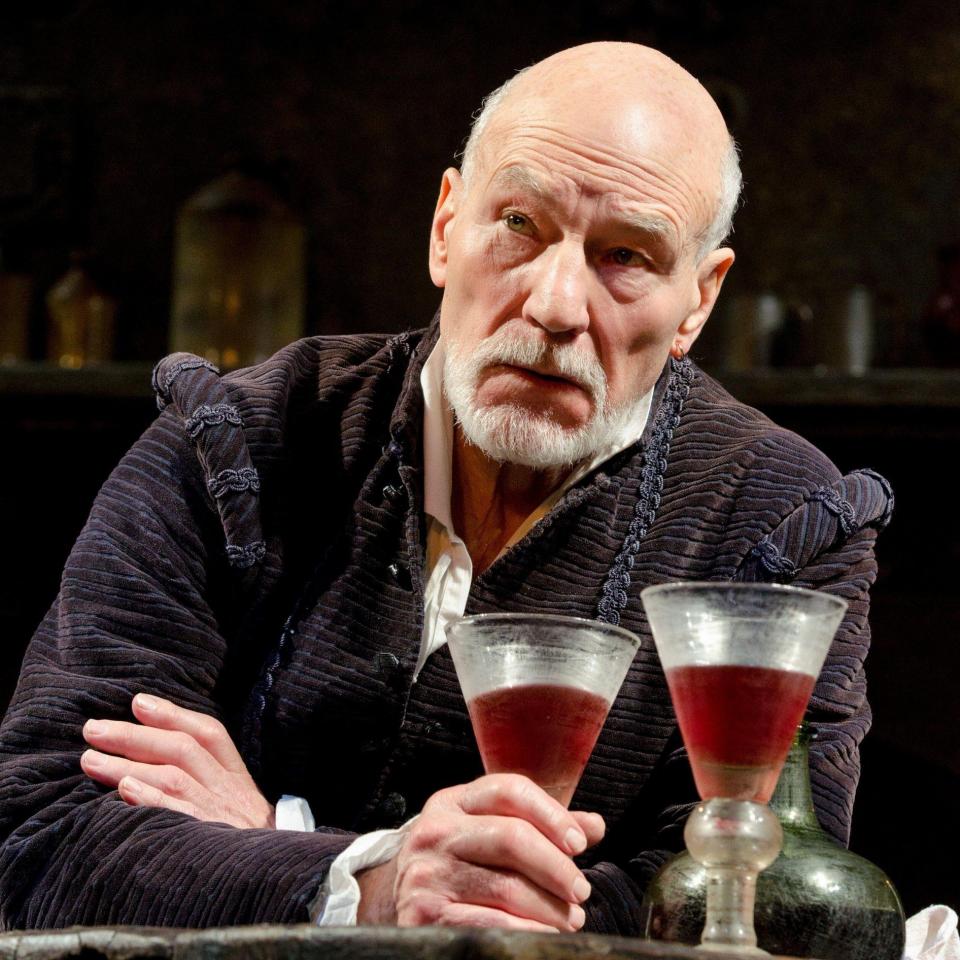

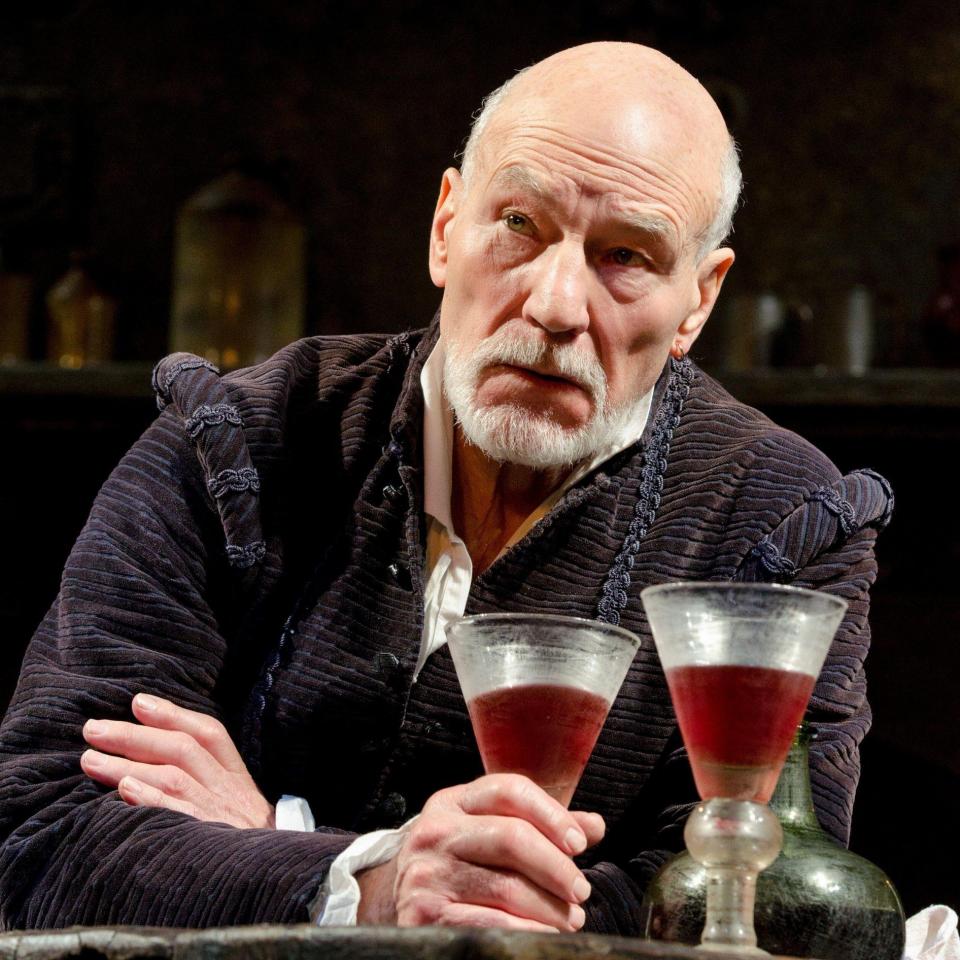

Yet his best work could be brilliantly unpredictable, his dialogue sharp and his stage imagination gloriously unbridled. Lear (1971) was a brilliant, brutal, modern rewriting of Shakespeare’s tragedy. And while Jonathan Kent’s revival of The Sea (a dark comedy set in Victorian East Anglia) largely washed over me, one optimistic thread stuck. “All destruction is ultimately petty, and in the end life laughs at death.”

Perhaps Bond’s plays will have the last laugh. His vision of a civilized society straddling destructive fault lines now seems more prescient than ever. The verdict has long been made on stage censorship, but I think the jury is still out on the full scope of Bond’s performance.