Bourdon House, a stone’s throw from Berkeley Square, may be in the middle of the crowds of 21st-century Mayfair – tourists taking selfies outside Louis Vuitton, and Annabel’s club dismantling its latest eye-catching exhibition – but the atmosphere here on a crisp winter morning is completely different. Behind those gleaming black doors – the very ones that greeted the Duke of Westminster when he lived here – is a private members’ club so discreet it would never deign to reveal its fees, all luxurious burgundy interiors and patrician dress codes. But the real action takes place upstairs.

Unlike most tailoring businesses, whose studios are typically located below street level, Dunhill’s bespoke operations are located on the upper floors of Bourdon House. It’s a pair of modest rooms where canvases dotted with the tiny print of each tailored jacket and trousers line the rails, and a whiteboard charts each item’s progress through the system, and who it’s for – a kind of tailor-made war. command. Its elevated position within Bourdon House means light floods the warren of rooms, ready for Dunhill’s new life under recently installed creative director Simon Holloway.

“There is a sense of responsibility in looking after the heritage of a house like Dunhill and its future trajectory,” says Holloway. French conglomerate Richemont – which counts Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels and Alaïa among its crown jewels – bought Dunhill in 1998. Holloway, who cut his teeth at Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren, was led across from historic British outfitter James Purdey & Sons, also owned by Richemont, in April 2023. “But I like to think Alfred Dunhill would approve of the direction we’re going in,” says Holloway, who replaced former creative director Mark Weston, and before him John Ray, previously Gucci’s head from the men’s clothing department. It’s fair to say there have been a few ups and downs over the last fifteen years, but Holloway’s focus is Dunhill: a nod to the impeccable tailoring that has been a success in our home, better known for its sportswear and accessories. .

‘We’ve seen a significant increase in suit sales, and I think this is because the pendulum is swinging back towards a more tailored silhouette from a fashion perspective. I think people have become so casual that they’re actually tired of slouching,” says Holloway. His first focus on arrival was the bespoke arm of the house, enlisting Savile Row’s secret weapon, William Adams – a tailor who has worked at some of the finest houses including Ede & Ravenscroft and Kilgour – to create the tailoring department and Holloway’s vision of refined, refined, elevated fit.

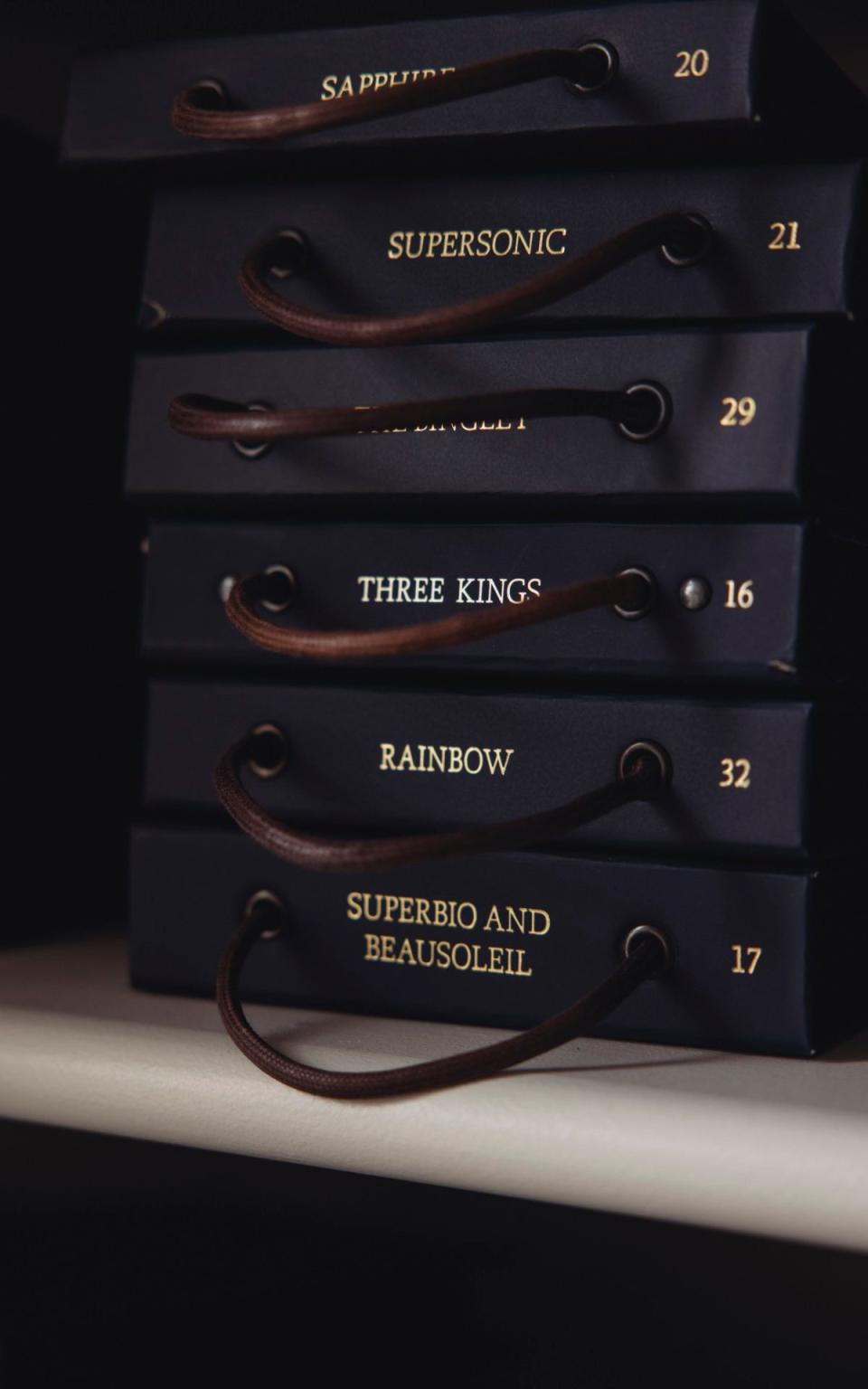

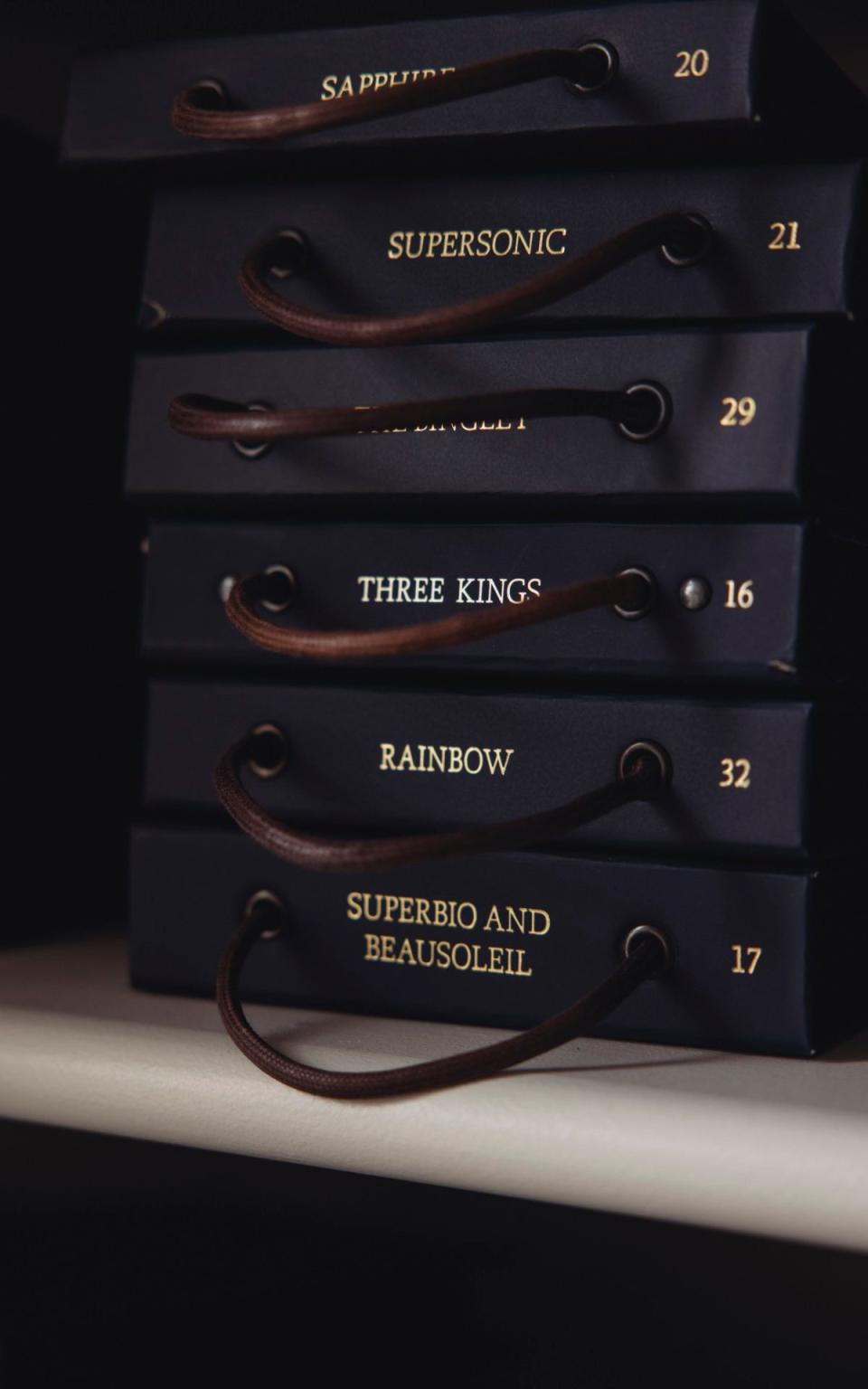

The nerve center of Bourdon House consists of three cutters, a trouser maker and two coat makers; the latter is the traditional term for the complex craft of making a jacket. The emphasis here is on manufacturing excellence. First, a customer sits down for a consultation in one of the beautiful rooms leading off the central staircase, and to browse through fabric samples, mainly those from British factories; Adams gestures to an inky expanse of navy blue pinstripes, destined for a single-breasted suit. The process involves consulting with the tailoring team on the details of fabric, style and fit – anywhere from one to three meetings to fine-tune the details, although repeat orders can be placed anywhere in the world as long as Dunhill has your measurements. Once the shape and structure have been determined – single-breasted or double, tuxedo jacket or something sportier – the entire process takes up to 10 weeks; costs depend on fabric choice and details, but expect a hefty four figures.

The most adventurous piece the bespoke studio has worked on to date was a fleece jacket with a difference: the polyester fabric was replaced with cashmere and the nylon accents with suede. But as a rule you can go here for special tailor-made suits for events and serious business meetings. They are working on up to 80 suits at any time.

“I wanted to refine the feeling that this is the pinnacle of British craftsmanship and the sense of handcraft and careful composition,” says Holloway of his interpretation of Dunhill’s tailoring. Connoisseurs can spot the signature stylistic details from miles away: the soft draping of Anderson & Sheppard, the pointed lapels of Edward Sexton. What does Holloway plan to do with Dunhill? “It will be a masculine silhouette,” he says. This will be welcome; After years of striking, oversized shapes at Zegna and Versace, or reed-thin, gender-fluid cuts at houses like Celine and Saint Laurent, the proportions of men’s suits have not been in favor of the common ‘classic’ for some time now. “Structure but with lightness, a very British feel and fabrics with a very English color palette and texture,” says Holloway, who worked with historic yarn makers in Hawick, Scotland, to formulate special fabrics. ‘There is a sense of Britishness at the heart of Dunhill.’

One of the few British-born luxury houses, Dunhill has perhaps more than ever stood for innovation and doing things with courage and courage. Alfred Dunhill was a pioneering young fellow who started as an apprentice at his father’s saddlery shop at the age of 15 and took over in 1893 at the age of 21. As technology changed, he responded by equipping the new world of cars and creating, as he put it, “everything but the engine.” A mischievous young Bertie Wooster could have had his Morgan dressed in Dunhill leather, Jeeves tucked away his white tie in his elegant suitcases and – by the Roaring Twenties – lighting his cigarettes with a Dunhill lighter.

In a way, the Dunhill man has always seemed rather glamorous. Choosing a Dunhill suit was actively choosing something edgier than the rather staid Savile Row; sport coats, car accessories and eventually an exuberant range of evening wear became his calling card. Fleming’s Bond loved his lighters, and Truman Capote wore Dunhill’s black tie for his 1966 black and white ball.

Back in the eyrie above Bourdon House, the tailors concentrate on the finer details of the robe effect on a shoulder, or the alignment of stripes on a lapel. “It’s important to thread a needle through an entire century of Dunhill in this new era,” Holloway says. The trusty suit is a solid place to start.