When 24-year-old Saul Leiter first saw Henri Cartier-Bresson’s prints at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1947, photographers were content to be considered photographers. The current aspirational ideal is ‘artist’ or ‘artist who uses a camera’. But if Leiter is a consummate artist, it is because his talents were uniquely served by – and completely dependent on – the camera in his hand.

It is tempting – and many people have been tempted – to describe this pioneer of early color photography as “painterly.” The upcoming exhibition Saul Leiter: An Unfinished World at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes – the photographer’s largest exhibition in Britain to date – features some of Leiter’s actual paintings. These small works are the equivalent of Cartier-Bresson’s drawings: interesting only because they were made by a great photographer. Painting – its history and Leiter’s hope to add to that history – is merely the backdrop to his signature achievement.

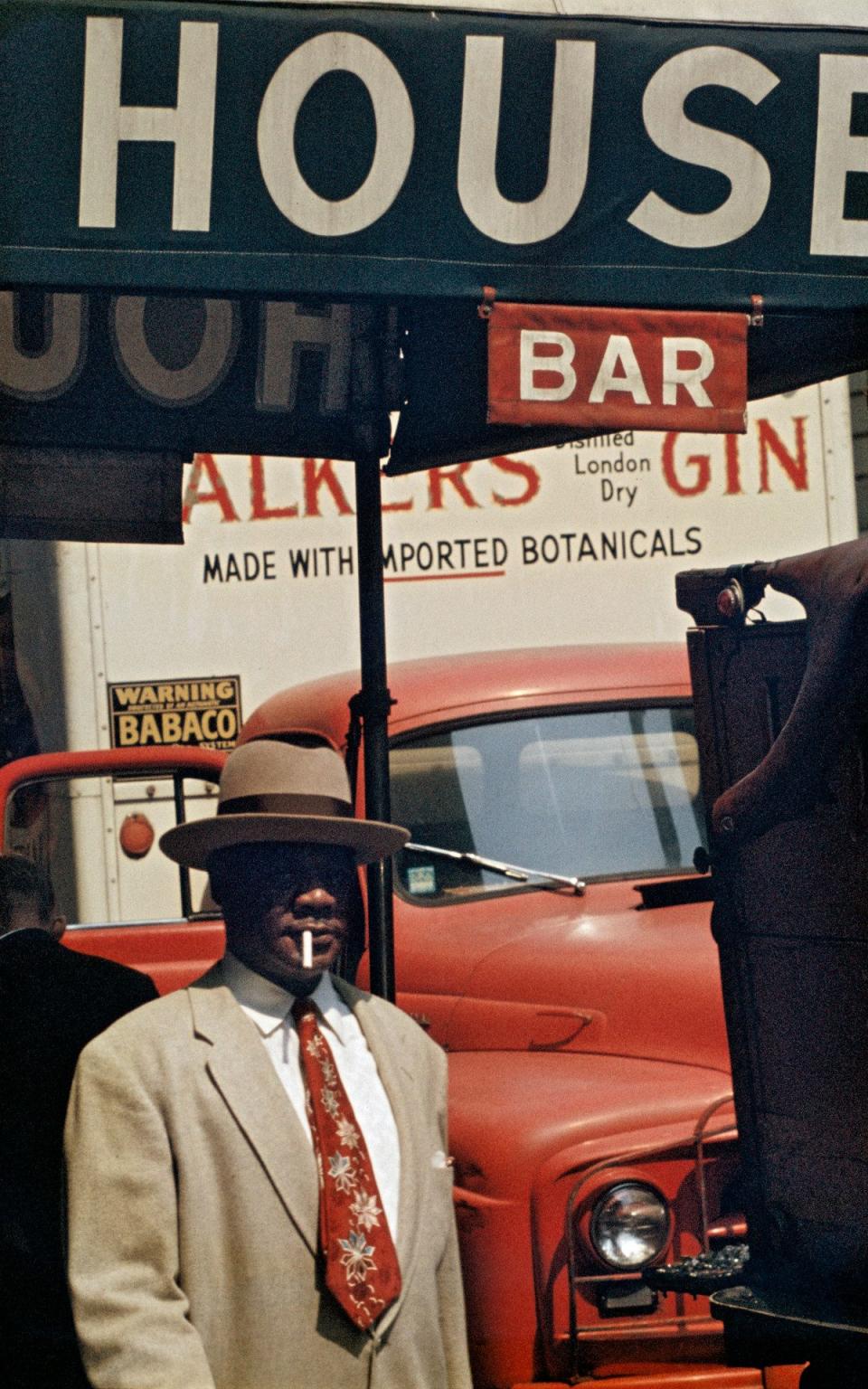

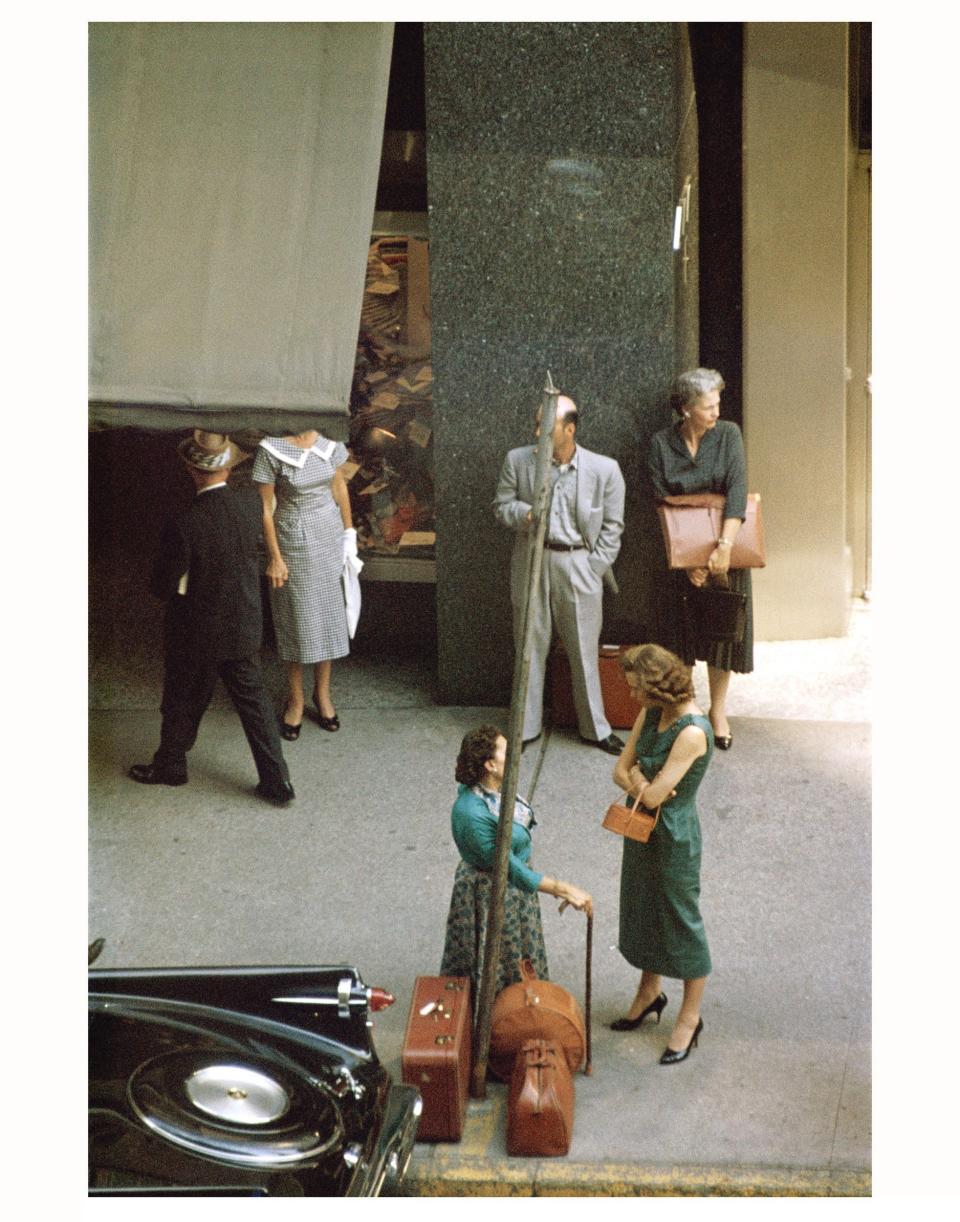

Leiter’s achievement is complicated for several reasons. From the 1950s to the 1980s, he enjoyed some success as a fashion photographer, contributing to publications such as Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue and Elle. But it was the unpaid, personal work that he devoted himself to and valued most. Much of this work was in colour.

Until the 1970s, the photography world seemed to share Robert Frank’s cantankerous assertion: “Black and white are the colors of photography.” Everything changed in 1976 with William Eggleston’s exhibition at MoMA – the museum’s first solo exhibition of color photography. A few American photographers had used color before – most notably Helen Levitt – but it was Eggleston who, in the words of curator John Szarkowski, “really learned to see in color.”

However, Leiter had taught himself to see a different kind of color decades earlier. While he worked in black and white – elliptical and lyrical street scenes, portraits of friends, nudes – from 1948 onwards he also quietly articulated his own language of color harmony. This work attracted little attention, even after photography had embraced the brave new world of post-Egglestonian color.

So this Pittsburgh-born son of a Talmudic scholar, who left his calling as a rabbi in 1946 to come to New York with the intention of becoming a painter, who photographed in color when serious photography existed only in black and white, continued to walk quietly. his non-corporate business, usually within walking distance of his apartment in the East Village. The tip of the miraculous iceberg resulting from his long patience was barely noticed until 1992, when the then 68-year-old was, appropriately and ironically, included in a book devoted to the so-called New York School. Seen in the context of this larger group, which also included photographers such as Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus, it became clear that Leiter’s style was entirely his own.

Unnoticed for forty years, a Leiter photograph became immediately recognizable following the publication of the book Saul Leiter: Early Color, by Steidl, in 2006. This lengthy delay – which Leiter seems to have regarded without frustration or bitterness – proved fruitful in several respects.

It meant, for a start, that there were many types of time in his photographs. They are records of the time they were made, but even this truth is ambiguous, as he had a penchant for using outdated film; the resulting deterioration was imbued with a desaturated appearance.

Although the places he photographed still existed by the time the photographs saw the light of day, the functions and storefronts had changed, the people on the streets had disappeared, and their clothing had gone out of fashion. So the photos had a kind of nostalgic immediacy, a contemporaneity that was also retrospective. Photographs, many taken by a young man now in his eighties, were at once old and new, revealing a way of seeing that was both ahead of its time and retrospective.

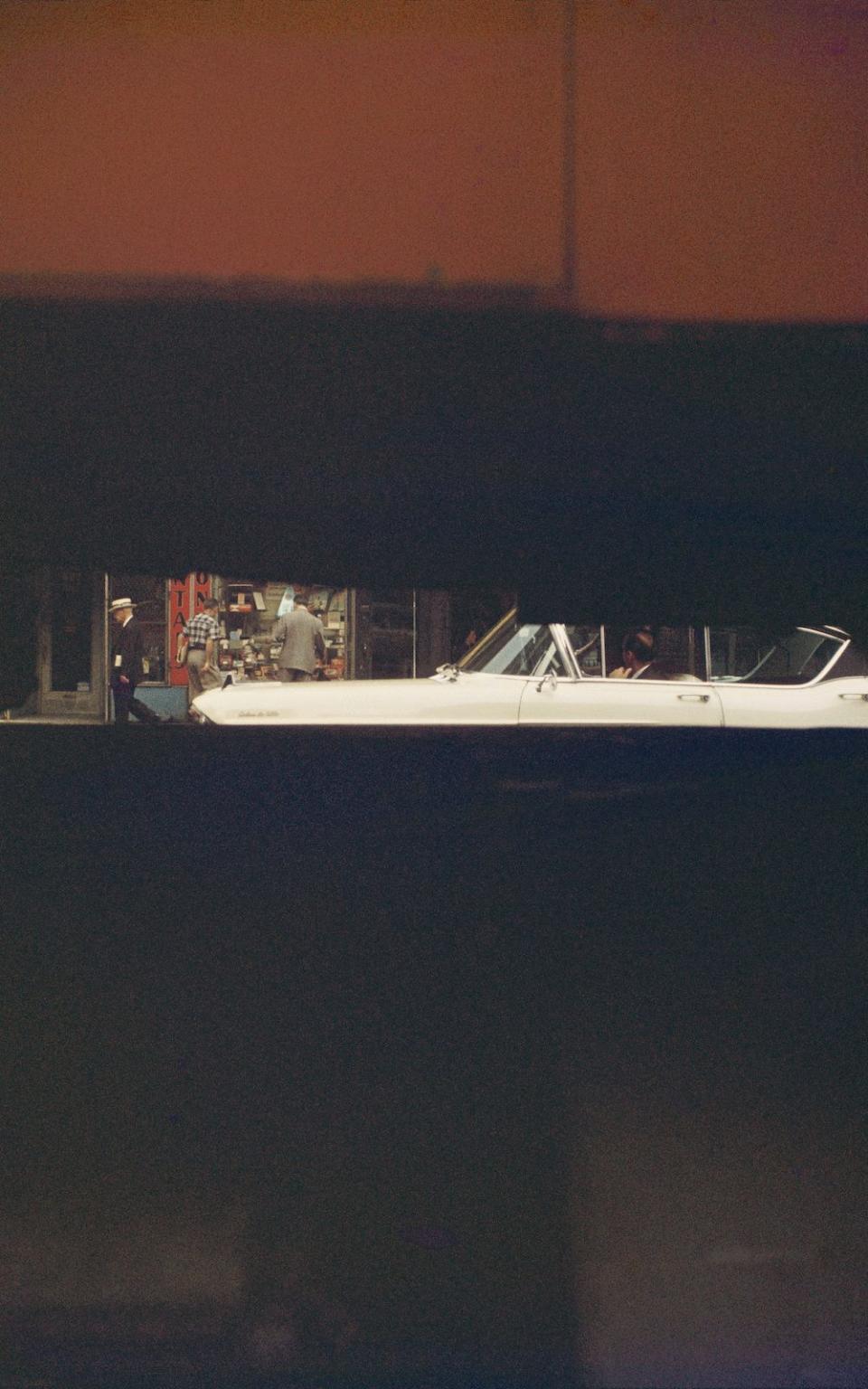

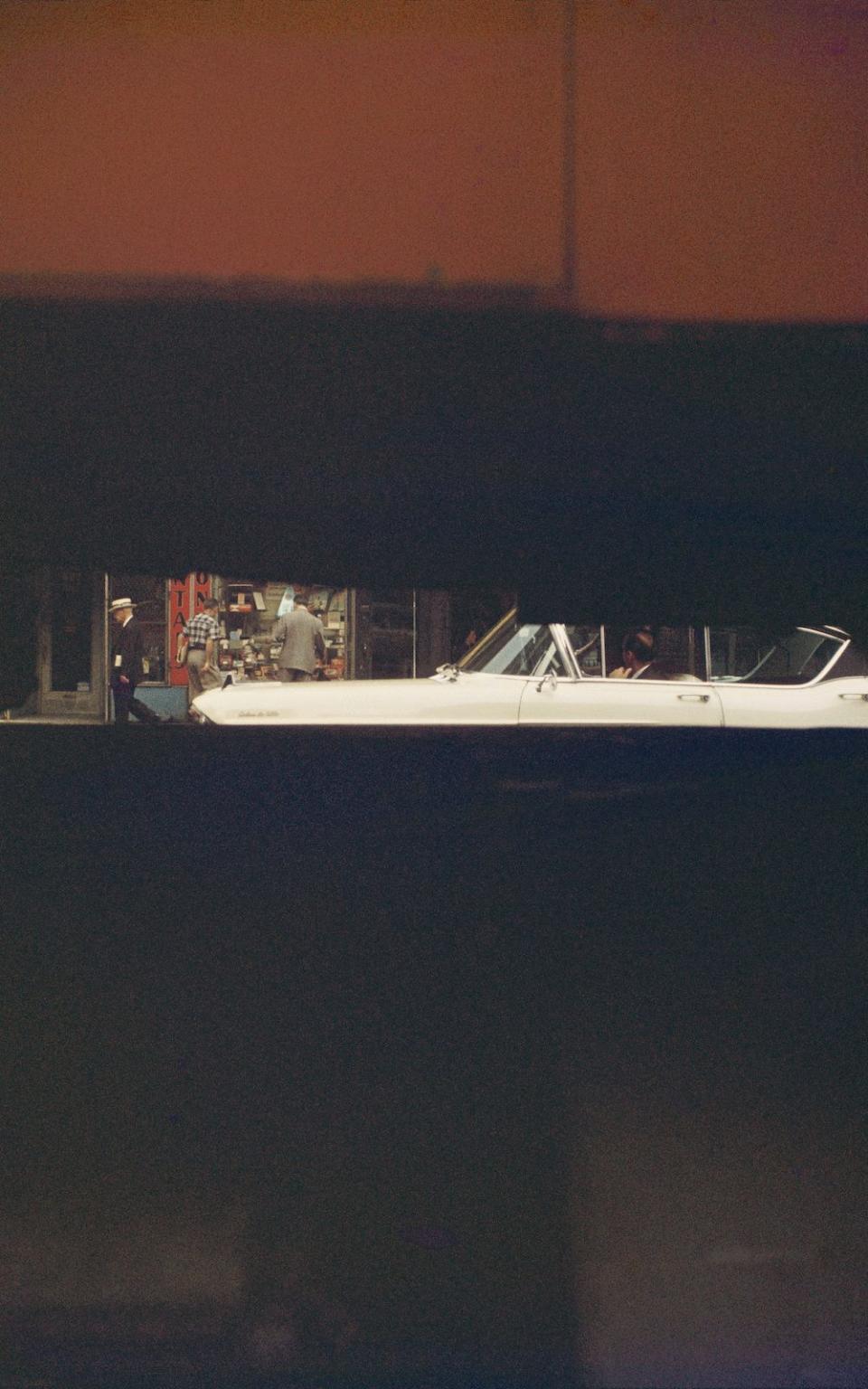

The documentary quality present in each photo was always weak in Leiter’s work, but after half a century it had diminished even further (no news value whatsoever) And intensified, as happens with any relic. At an exact moment – often difficult to pinpoint – a piece of the world looked different this, even as Leiter pushed what he saw to the soft edge of abstraction. This is evident from Leiter’s 1957 recording Through Boards, used on the cover of Early Color and on display in the MK Gallery: Rothko’s red-black eternity with, in the middle, a band of time-specific information in the form of a street, cars, shops and people.

Resolved contradictions are at the heart of Leiter’s magic. The colors flow slowly, as if they have not yet been completely set. His exteriors are often seen from the inside through foggy windows – such as Pull, made around 1960 – or reflected through rain-stained windows. The hectic streets are framed unhurriedly, contemplatively and therefore internalized by a consistently shaping consciousness. This gives his images a subtle psychological depth, while – another harmonious contrast – the frequent use of a telephoto lens flattens the pictorial surface. “The concept is interesting,” writes John Ashbery in his 1977 poem “Wet Casements”:

to see, as if reflected

In streaming windows, the

looking through others

Their own eyes. A summary of them

correct impressions of

Their self-analytic attitude

covered by your

Spooky transparent face.

It seems inappropriate to mention a very English poet in the same breath as Ashbery, but Philip Larkin’s phrase “snow fell, undated” could serve as a caption for Leiter’s many photographs of streets in which snow – the white of black and white of color ! – buries or blurs the identifying marks of time and place. In Footprints (circa 1950), snow causes the rising red of an umbrella to blossom, as if from a source that lies both in the future and in distant memories.

These snowstorms contribute to the felt silence of the photos: muted colors that double the romantic intimacy, the coziness from outside, perceived from within. So the scenes also contain our reactions to them, or – going back to those extended notions of time – ours reflections on them. Just looking at the photos places us inside them.

Leiter had a sour feeling of how skillfully he had avoided success and in some ways the neglect may have been a heavily disguised blessing. Could he continue to work the way he did if he was recognized and noticed enough? Not only because the observer on the street, instead of being able to wander discreetly and very quietly through the neighborhood, would have been observed by people who saw the great Leiter at work; more treacherous, he would have become aware of the Leiter thing.

Had he continued to show the same material year after year, work now receiving critical acclaim might have aroused the dismay of critics eager for change, a development of which, as far as we can see, there is mercifully little. Unlike his colleagues, Leiter had no formative legacy. The world did not configure itself around or in response to his work; Until recently, we didn’t see real-world Leiters everywhere.

Even more time has passed since he was discovered – more snow has fallen and much of it is dated – and the way we look at Leiter’s photos, what we see in them, is changing. Most of the work seems poignantly more beautiful than ever – but not all. The nudes have suffered, not so much because we are forced to see suspicious images of women sprawled on beds in suspenders and stockings, but because these women smoking. Ugh!

There is an irony in Leiter’s fleeting snapshots, which take us back to the language of paint – to the late 19th-century intimate French painter Edouard Vuillard, whom Leiter cited as an influence. As a contemporary once noted of Vuillard, “the element of fantasy” in his work obliged him “to stick to these small panels; it would be impossible for him to go further… If he had to work on a large scale, he would have to be more precise – and then what would become of him?”

The acclaim came so late to Leiter that the question only arose posthumously. Since his death in 2013, at the age of 89, several attempts have been made to ensure that his name is written large – and bigger. The danger of enlarging him in this way – larger prints, larger format books – is that it conflicts with his essential aesthetic and identity. And of course he became a late influence. Todd Haynes’s film Carol (2015) was so steeped in Leiter’s palette and visual vocabulary that it sometimes resembled a moving retrospective. Lately, this most local of photographers has become global, so to speak. In the meantime, the history of photography had to be reshaped around him to do him justice. But his name, like Vuillard’s, must still be written small so as not to obscure himself.

Geoff Dyer’s books on photography, The Ongoing Moment and See/Saw, are published by Canongate; Saul Leiter: An Unfinished World is on view at the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes (mkgallery.org), from today until June 2