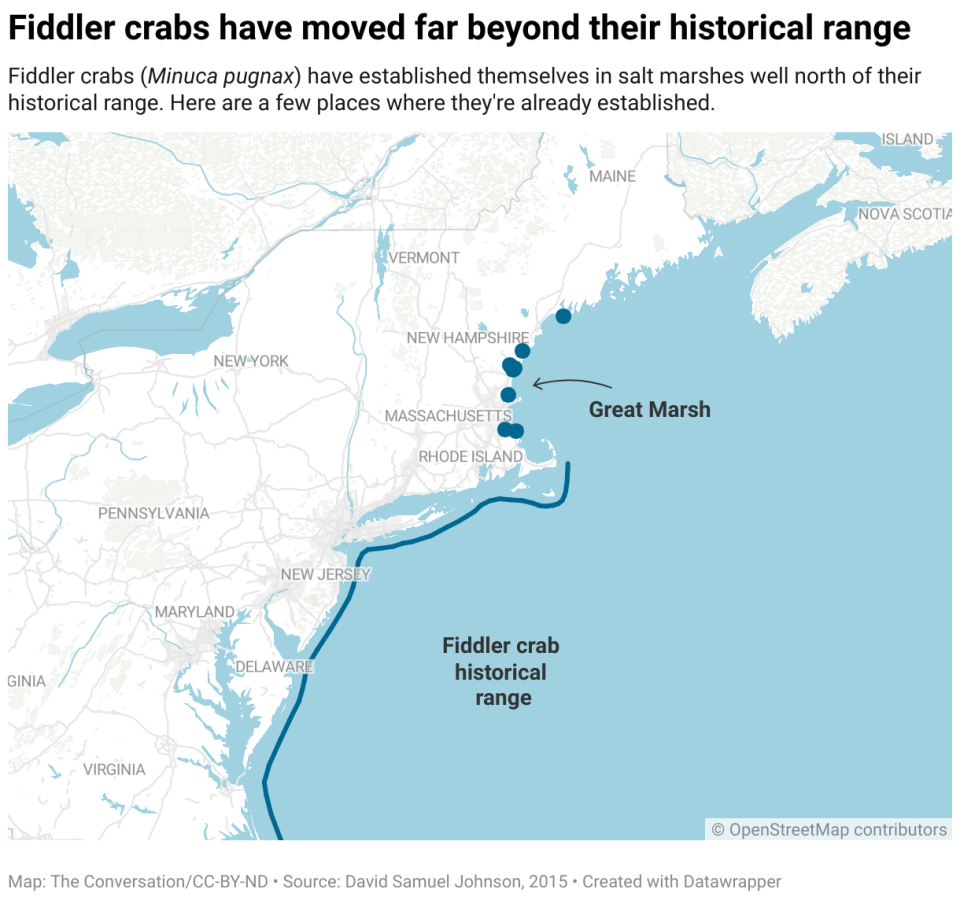

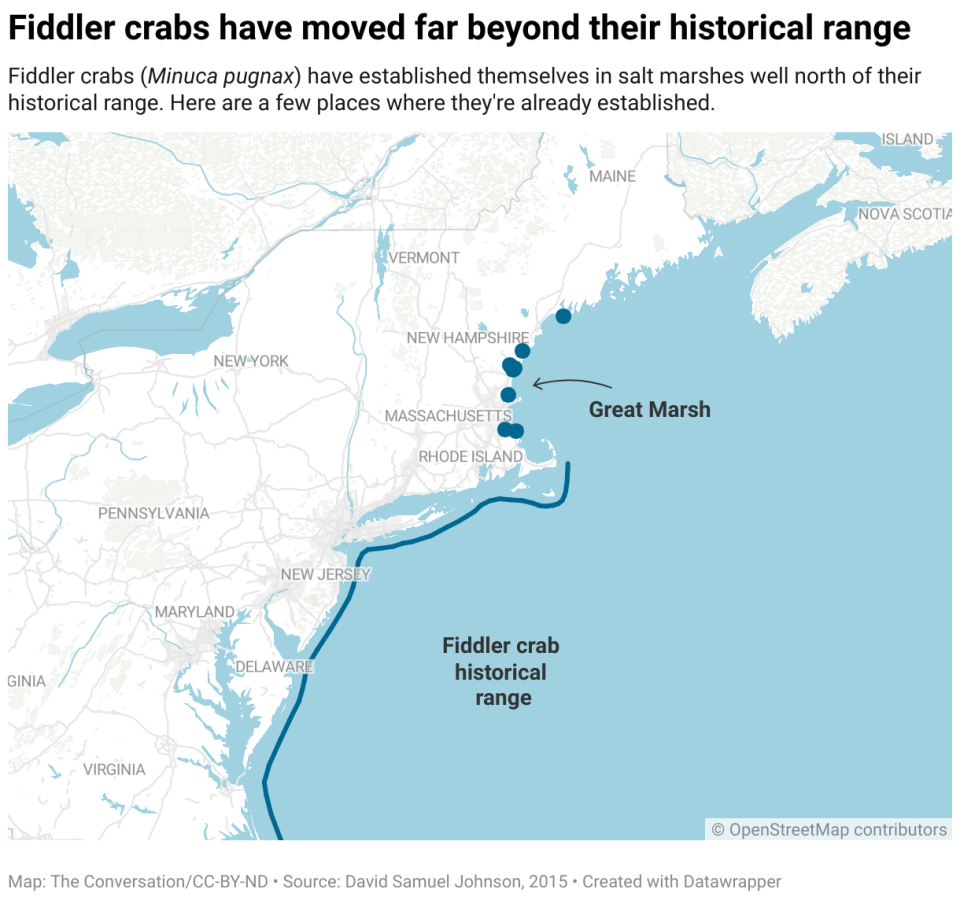

Nine years ago, I stood on the muddy banks of the Great Marsh, a salt marsh an hour north of Boston, and pulled a thumb-sized crab with an absurdly large claw from a hole. I was looking at a fiddler crab – a species that wasn’t supposed to occur north of Cape Cod, let alone north of Boston.

It turned out that the swamp I stood in would never be the same again. I witnessed climate change in action.

The Great Marsh is located on the Gulf of Maine, the stretch of the Atlantic Ocean that extends approximately from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Nova Scotia, Canada. The marshes along the gulf are crucial breeding grounds for many bird species. But the water there is warming faster than anywhere else in the world. And with warming water comes warm water species.

Maryland blue crab and black sea bass, both southern species, are now being caught in Maine lobster traps. And fiddler crabs, whose charismatic males have oversized claws to attract mates and defend themselves against rivals, are marching along the eastern seaboard.

This rapid migration is partly due to their young. While adult fiddler crabs scurry around in the mud, their young swim in the water and are carried away by the current. The warming water allows them to complete their life cycle, and the current carries the next generation further north.

As a marine ecologist who has worked in the Great Marsh for decades and studies climate migrants—species that have shifted or expanded their ranges due to climate change—I want to know how these migrations affect the ecosystems they move to. I was surprised to find fiddler crabs in the Great Swamp, but I was more surprised by the way they are affecting the swamp.

Fiddler friend turns enemy

Salt marshes are grasslands that are flooded by the sea every day. Imagine a Midwestern prairie as oceanfront property.

South of Cape Cod, decades of research has shown that grass is more productive when fiddler crabs are present. Fiddler crab poop and burrows release nutrients and fuel plant growth. They are the earthworms of the salt marsh; they help plants grow.

But in the Great Swamp it doesn’t work that way.

Burrowing by fiddler crabs reduced shoot and leaf biomass in the Great Marsh by 40% and roots by 30% over the summers of 2020 and 2021. That’s the opposite of what we would predict for summer growth.

I was surprised because the crabs lived next to the same plant species. Spartina alterniflorain the Great Marsh, as they were south of Cape Cod.

Why the different effects? One reason is that although these plants belong to the same species, they did not evolve with fiddler crabs like their southern relatives. Fiddler crabs don’t eat the grass, but when they dig, they damage the grass from Sparta carrots. Plants in southern areas have adapted to this damage and are now benefiting from it, but plants in the north have yet to adapt.

A chain reaction through the ecosystem

The damage from this disturbance could extend far beyond the grasses and affect the rest of the Great Swamp food web.

Insects, spiders, snails and small crustaceans all depend on the grasses for food. These animals in turn are food for fish, shrimp and crabs. Less plant biomass could lead to fewer fish and shrimp. The many birds that breed in the swamp and stay there during migration depend on that food web.

Will this damaging relationship with crabs continue forever for the plants? Probably not. Spartina has been able to adapt to new circumstances within decades. Plants in the Great Marsh and the rest of the Gulf of Maine will also likely adapt to the fiddler’s presence over time.

In the meantime, however, fiddler crabs may increase the effects of climate change in the area.

Accelerated sea level rise due to global warming already threatens to drown the Great Swamp. Salt marshes have kept pace with sea level rise for millennia, just as you might deal with rising water that threatens your home: by building up. Plants build marshes by capturing sediment brought in by each tide. Less grass could mean less swamp, and the swamp could drown.

Fiddler crabs also reduce the Great Marsh’s ability to store carbon. Salt marshes are gigantic compost piles that take centuries to rot, if ever. Every gardener knows that temperature and oxygen get a compost pile cooking. This is why you turn your compost.

Every year, dead plant roots are buried in soils lacking oxygen. As a result, decomposition is significantly slowed, allowing the “compost” and carbon to accumulate and be stored. Therefore, salt marshes are crucial as places where carbon is stored, keeping it out of the atmosphere where it would contribute to climate change. However, fiddler crab burrows encourage decomposition. The dead plants begin to rot and the carbon, once buried, is released.

Climate migrants occur worldwide

Fiddler crabs are just one of thousands of climate migrants we’ve seen worldwide. Although ecosystems will adapt as climate migrants arrive, they will likely never be the same again.

In Australia, as a herbivorous sea urchin expanded its range south, plant and animal diversity declined after kelp forests were denuded. In California, a predatory nudibranch (also known as a sea slug) reduced the local population of other nudibranchs as it migrated north. In Antarctica, krill move south. Krill is the main diet for whales, penguins and seals, so this shift could disrupt the Antarctic food web.

But it’s not always bad news when climate migrants appear.

When mangroves replace swamps in the southern United States, they store more carbon. Climate migrants can also benefit fisheries.

My lab studies the blue crab, famous in the Chesapeake Bay, which generated more than $200 million in dockside landings in 2022. With blue crabs being found in lobster pots in Maine, a fishery could be developed in northern Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine. However, it is unknown how blue crabs and lobsters get along.

In Virginia, warming waters have brought an abundance of white shrimp, along with a new fishery. To the delight of anglers, snook – a fun sport fish – has expanded into Florida’s Big Bend in the Gulf of Mexico.

There is still more migration to come

The year 2023 set a record for heat waves in the world’s oceans, and with greenhouse gas emissions still rising, warming will continue.

Although climate migrants are not considered invasive species, they can alter ecosystems, as we are already seeing in the Great Marsh. It’s important to understand how that happens, and whether ecosystems can adapt as species continue to change their zip codes.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and analysis to help you understand our complex world.

It was written by: David Samuel Johnson, Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences.

Read more:

David S. Johnson receives funding from the National Science Foundation.