For the first time, the public can enter Balmoral in a series of special (now sold out) summer tours. This Aberdeenshire estate symbolizes the Royal Family’s special relationship with Scotland, but Balmoral means more than that: it reflects a romantic image of Scotland known around the world, an image that the Royal Family played a key role in creating .

This ‘Balmoralization’ is a crucial part of Scotland’s story. It is a story of how English and Scottish Unionists cultivated a new idea of Scotland that linked these two old enemies. When foreign tourists think of Scotland these days, they often think of wild moors, rugged castles, bagpipes and especially tartan. These elements have always been part of Scottish culture, but the reason they became ubiquitous was due to a clever rebranding exercise in which royalty played a leading role.

This royal makeover began 200 years ago, in 1822, with King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh. It was the first visit to Scotland by a British monarch since the 17th century. There was a good reason for this long absence. The 18th century had seen three Scottish rebellions against the English, three attempts to overthrow the British Hanoverian monarchy and restore a Stuart to the throne.

The Stuarts were Scottish and Bonnie Prince Charlie was the last of these Scottish pretenders. Tartan was the uniform of his Highland soldiers, so after his rebellion tartan was banned. The genius of the British monarchy was to transform this rebellious garb into the costume of Unionist Scotland – a sign of loyalty to the crown rather than a sign of rebellion.

Ironically, it was the Hanoverian King George IV who sanctioned this appropriation of Highland dress by the Unionist establishment, aided by Scotland’s greatest writer, Sir Walter Scott. Scott’s historical novels were hugely popular – especially Waverley, his dramatic tale of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s rebellion – and when he was hired to direct George IV’s Scottish visit, he transformed Edinburgh into a sea of tartan.

Scott organized a series of banquets and cavalcades to mark this royal visit, and he urged his civilian Lowland guests to come along in traditional Highland dress. Many of these Lowland townspeople were bewildered. Their ancestors had fought alongside the English against Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Highland rebels. Edinburgh was the capital of the Scottish Enlightenment, a city of doctors, lawyers and academics, not country lords and Highland chiefs. But after King George had his portrait painted in full Highland dress, they obediently followed suit, and tartan became the house style of these festivities.

Following George IV, tartan became mainstream in Scottish society as Scott’s novels fed a growing hunger for an idealized version of Scotland’s past. Never mind that the Highlands had been much more densely populated before the Clearances. It doesn’t matter that the Lowlands were now the cradle of the industrial revolution. Readers did not want gloomy stories about industrialization. They preferred to read nostalgic fantasies about an untamed wilderness, populated by fierce warriors and flame-haired maidens.

One of Walter Scott’s many fans was George IV’s niece, Queen Victoria. In 1842, she traveled to Scotland with her husband, Prince Albert, to visit the locations in Scott’s novels. In 1847 they holidayed at Adverikie, near Inverness, and in 1848 they discovered Balmoral. It was the beginning of a royal love affair with Aberdeenshire that continues to this day.

The most important thing about Balmoral was that, despite its ancient aesthetic, it was actually a thoroughly modern creation. There was already a house on the estate, but Victoria and Albert wanted something bigger and more comfortable, so they built another house next door. The architectural style was Scottish Baronial: faux-medieval on the outside, fully equipped on the inside, a fitting metaphor for their sincere but sentimental relationship with Scotland.

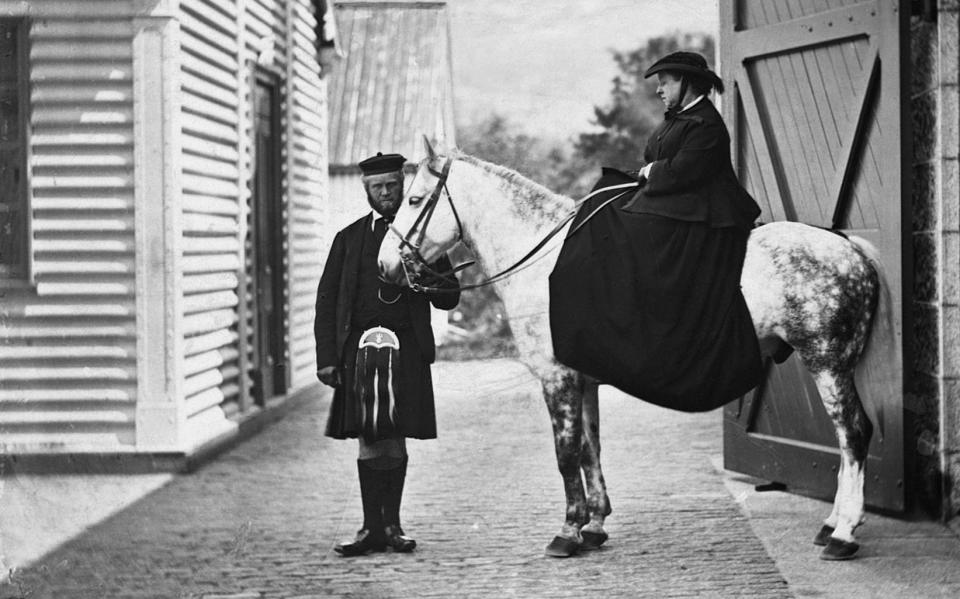

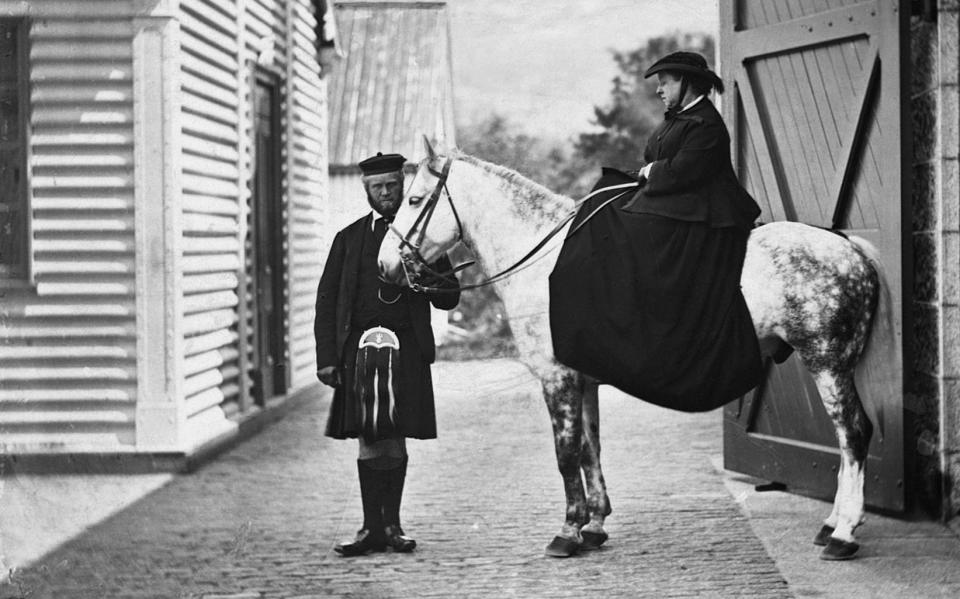

Victoria’s family tree was predominantly German, but she had some Scottish blood, and to celebrate her (relatively tangential) Scottish heritage, she decorated Balmoral with tartan: green Hunting Stewart; white dress Stewart and red Royal Stewart. She dressed her servants in kilts and sporrans. One of her prime ministers, Lord Rosebery, called her tartan drawing room the ugliest room in the world.

Rosebery had a point – Victoria’s decor was quite boring – but some things are more important than good taste. This ersatz Caledonian decor served a higher purpose. As Scottish historian Michael Lynch noted in his astute book ‘Scotland – A New History’: ‘The Scottish nature of Balmoral helped to give the monarchy a truly British dimension for the first time.’ And despite a few recent hiccups, it’s a dimension that has lasted.

“All seemed to breathe liberty and peace, and forget the world and its sad turmoil,” Queen Victoria wrote poetically of Balmoral, and it is clear that her great-great-granddaughter felt in her own, more down-to-earth way, Queen Elizabeth II pretty much the same. During her 70-year reign, she spent most of her summers here, along with her father, King George VI, and her grandfather, King George V.

With numerous homes to choose from, what drew Elizabeth to Balmoral? The late Sir Malcolm Ross, Comptroller of the Royal Household, said it best. “It’s the setting, it’s the place, it’s the atmosphere,” he explained. “It’s the wide open spaces. No distractions, no planes, no noise, no traffic – just this beautiful estate where she can roam freely.” The estate includes 50,000 hectares of pine forest, farmland and moorland, home to red deer, grouse and highland cattle. Elizabeth loved walking, riding and picnicking here with her dogs.

Elizabeth remained true to Victoria’s Caledonian home style: the Queen’s Piper played the bagpipes every day at 9am (a tradition started by Victoria); the upholstery featured heather and thistle motifs; the walls were covered with Scottish landscape paintings and the antlers of deer shot on the estate. Still, her lifestyle here was more informal than in London, and that was part of the appeal. The visiting Prime Ministers were pleasantly surprised to see Her Majesty tidying up after the meal, stacking the crockery and washing the dishes.

Balmoral was also a welcome retreat for the Duke of Edinburgh. Elizabeth’s devoted husband manned the grill at countless Balmoral barbecues. He also helped maintain these gardens, adding herbaceous borders and water features. The devoted couple spent the pandemic at Balmoral, where they celebrated their 73rd (and final) wedding anniversary.

They both had close ties to Scotland, albeit for different reasons. Prince Philip’s love of Scotland stemmed from his school days in Gordonstoun. Queen Elizabeth was actually half Scottish; her mother came from an ancient Scottish clan and grew up in Glamis Castle, one of Scotland’s most historic country houses, the setting for Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

Elizabeth’s love for Scotland extended far beyond Balmoral and encompassed the entire nation. At the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 2021, she spoke of her “deep and abiding affection for this beautiful country”, a country whose public image her family had done so much to shape.

Does it matter whether that public image is partly fantasy? Does it matter that Scotland isn’t all grouse, deer and Highland games? Not really. All travel, all tourism, is partly an act of imagination. We see what we want to see, we find what we want to find. Of course, Scotland has more to offer than Balmoral, but it is still part of Scotland, and the things it represents, the things Elizabeth advocated for, are real.

The king’s Scottish roots run as deep as those of his late mother. Educated in Gordonstoun, like his father, his love of Balmoral is reflected in his charming children’s story, The Old Man of Lochnagar, named after the highest hill on the estate, one of seven Munros (peaks over 3,000 feet) within its boundaries.

Like his late mother, Charles’ love of Scotland is not limited to Balmoral. There are countless examples of his philanthropy, but Dumfries House is a particularly good example. Dumfries House, built by John and Robert Adam and decorated by Thomas Chippendale, is one of the best-preserved Palladian houses in Britain, and when it came up for sale in 2007 it seemed that its priceless collection would be lost forever, until Charles led a consortium that bought it for the nation.

Thanks to Charles’ charity, Dumfries House remains open to the public and its valuable contents remain on site, but it’s not just a dusty old museum. The house also provides employment and training to many local young people, in an area struggling with high unemployment. Dumfries House shows that ‘Balmoralisation’ at its best is more than mere nostalgia. As Charles has shown, it can also be a progressive force.

The Balmoralization of Scotland was clever PR, designed to integrate a turbulent nation into Britain, but like all the best PR campaigns it was used to sell a brilliant product. The tartan clichés may be corny, but they are rooted in reality. Much of Scotland remains wilderness and its cultural heritage remains unique.

Queen Elizabeth was right about Scotland, as she was right about so many things. “It’s the people that make a place,” she said, “and there are few places where that is truer than Scotland.” How fitting that she should have died in her beloved home, Balmoral.

This article was first published in September 2022 and has been revised and updated.