Nine hours and 30 minutes before New York. Five hours and 30 minutes ahead of London. Three hours and 30 minutes behind Tokyo.

For more than a century, Indian clocks have officially stayed below the hour when calculating the time difference with most countries.

And while it is part of a small group of countries and territories that share this 30-minute gap – including Iran, Myanmar and parts of Australia – India is perhaps the most unlikely outlier.

The huge South Asian country geographically spans two time zones, but to the frustration of some groups, it is clinging to its unusual clock settings and refusing to part with a system that has a very complicated past.

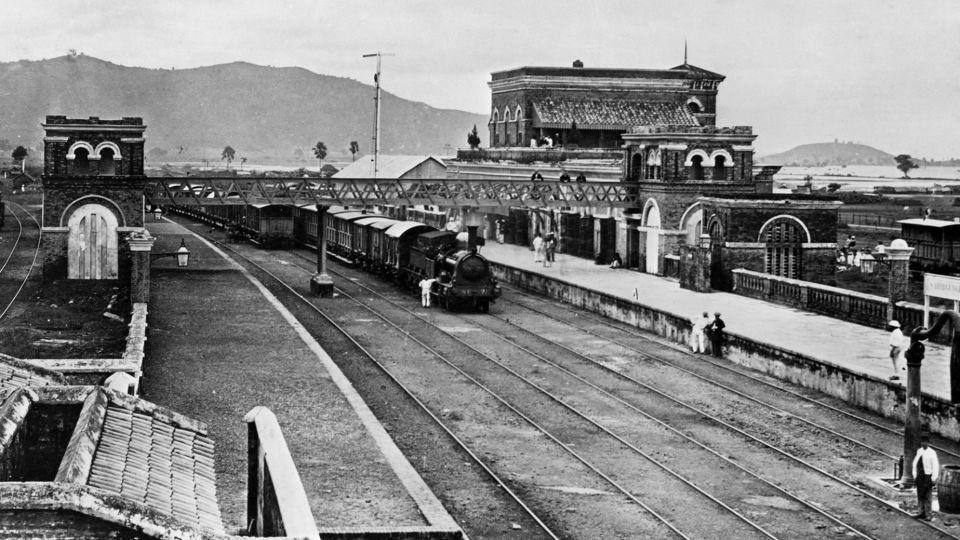

India’s half-hour zone dates back to India’s colonial rule and the era when ever-faster steamships and trains made the world a smaller place.

Until the 19th century, India – like most places in the world – operated on very localized times, which often varied not only from city to city, but from village to village. But playing a key role in the background was the East India Company, a ruthless and powerful British-owned trading organization that gradually took control of large parts of the subcontinent.

The East India Company operated one of Asia’s first observatories in Madras (now known as Chennai) in 1792. Ten years later, the first official astronomer of this observatory declared that Madras Time was ‘the basis of Indian Standard Time’.

However, it took a few decades, the advent of steam locomotives and the commercial interests of the East India Company to make that happen.

“The railways had an enormous influence on the colonial powers,” says Geoff Gordon, senior researcher in public international law at the University of Amsterdam.

“Before the railways won the battle for Madras time, there was a struggle between the mighty cities – Bombay and Kolkata,” Gordon adds. “That fight didn’t last long.”

Meanwhile, similar debates around the world, driven by the need to better coordinate transcontinental rail traffic and improve maritime navigation, led to the creation of the first international time zones at a conference in Washington DC in 1884.

The zones were based around the Greenwich Meridian, a line of longitude that runs from north to south through the Greenwich Observatory in London. Time zones east of the meridian generally fall later than Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), in hourly increments.

It took a while before the system was introduced worldwide. In India, people were still arguing about Madras Time. Despite the time being adopted by the country’s railways, the country faced significant opposition from workers and local communities unwilling to impose rigid new timings.

“There is less room to maneuver because your work rhythm is no longer connected to your boss down the street, the church bell and the twenty other people you will be working with,” says Gordon. “But it is now determined by the railway arriving once a day.”

Finally, Madras Time was established nationwide in 1905, with only a few holdouts remaining.

In the early 20th century, there was some pressure from scientific associations to align Indian time with GMT.

The Royal Society in London proposed two time zones for India, both in full-hour increments relative to GMT and each other: six hours before GMT for the east and five hours for the west of the country.

That recommendation was rejected by the colonial government, which opted for a uniform time that was right in the middle: five and a half hours before GMT.

“It seems to me typical of the colonial mentality,” says Gordon.

And so, in 1906, the British rulers of India introduced what is now known as Indian Standard Time.

The politics of the times

While the 30-minute difference is a lingering remnant of India’s colonial past, some countries have recently changed their own time zones.

Venezuela’s former president Hugo Chávez turned the clocks back half an hour in 2007 to give schoolchildren more daylight, a move later reversed by current leader Nicolas Maduro.

In 2015, North Korea got out of step with South Korea by creating ‘Pyongyang Time’, which put the country eight and a half hours ahead of GMT instead of nine.

However, colonial-era time zone decision-making in India reflected a chorus of political, scientific and commercial voices, both inside and outside the government, Gordon says.

He compares India during this period to ‘Brazil’, the dark dystopian science fiction fantasy film from 1985 directed by Terry Gilliam, or the comically complicated constructions drawn by the American cartoonist Rube Goldberg.

“It’s just this incredibly haphazard Rube Goldberg-esque construct, built up by a lot of different inputs, a lot of people acting opportunistically, a lot of people acting naively,” he adds. “There was a lot of strangeness and wildness.”

The consequences of a single time zone

India’s single time zone has been the subject of much debate over the years, with people in the northeast demanding a separate time zone given the size of the country.

Although this problem is not unique to India: Geographically, China is the third largest in the world and still has only one time zone, which, according to a 2014 study, is symbolic of the state’s centralized control over people’s daily lives.

India’s official timekeepers, the National Physical Laboratory, even called for two separate time zones over the issue, citing reports that Indian time is “badly affecting” the lives of people in the Northeast.

Instead, it proposed two time zones: five and a half hours ahead of GMT for one side of India, and six and a half hours for the other side, specifically what they have described as ‘extreme northeastern regions’, including areas like Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. .

“Despite geographic differences — such as the sun rising and setting almost two hours earlier in the Northeast compared to Gujarat — both regions share the same time zone,” said Maulik Jagnani, an assistant professor of economics at Tufts University.

Jagnani published a widely cited article in 2019 highlighting the impact of sunlight on natural circadian rhythms in India, with a focus on children.

“This arrangement affects children’s sleep patterns […] children exposed to later sunsets go to bed later,” Jagnani adds. “Fixed start times for school and work do not allow for corresponding adjustments in wake-up times, leading to less sleep and poorer educational outcomes.”

The NPL also acknowledged this problem, adding that the impact of the circadian rhythm on health and work efficiency is related to the “overall socio-economic development of the region.”

However, it looks like India’s unusual time zone is here to stay. When the issue of introducing two time zones was put to the Indian parliament in 2019, a government committee rejected the concept for unspecified “strategic reasons.”

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com