Recently I was invited to watch a match from one of the hospitality boxes at the new Tottenham Stadium. It was a cold night and as we sat in the large armchairs that offered an uninterrupted view of the field, my host pointed to a switch in the armrest.

“Heated seats,” he said.

That’s not what those of us who grew up in the old school would expect at a football game.

But everything has changed in recent decades. Stadiums that were once death traps have transformed into comfortable, multi-functional entertainment destinations. When Everton move into their new Bramley Dock home, they will become the seventh Premier League club to move into newly built, state-of-the-art premises since the millennium. Provided, of course, that they are not relegated to the Championship.

At the heart of the stadium revolution was the global architectural partnership Populous. Since their first British project – the John Smiths Stadium in Huddersfield – they have spent thirty years designing the buildings that have come to define the way we watch sport. From Wembley and the Principality Stadium, through the Emirates and Tottenham, to Wimbledon’s Center Court and the stand at Ascot, they have been responsible for much of this country’s new sporting infrastructure.

And not just in Great Britain. The futuristic view of the BBVA Monterrey Stadium in Mexico, where matches will take place at the next World Cup, is one of them. As does the Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad, the largest cricket ground in the world and at the heart of the Indian city’s bid to host the 2036 Olympics. And don’t forget the amazing Lusail Stadium in Qatar, where Lionel Messi won the World Cup this time last year.

The next major landmark on the horizon is Manchester United’s aging and creaking Old Trafford, which, as Telegraph Sport revealed on Boxing Day, has already come up with a recommendation from Populous for complete demolition and the construction of a new £2 billion stadium .

Earlier this month the company hosted an exhibition of their work, and I had the privilege of getting a tour from the company’s president, Chris Lee, the man who said this week that a brand new stadium is the best of the three current options – the others are a complete redevelopment or a minor makeover.

“Stadiums used to be functional exercises,” he explains, as we look at photographic evidence of Populous’ global reach. “Not anymore. Now they are considered cultural heritage.”

More than that. As will soon become clear as Liverpool’s derelict old port area is reborn around Everton’s new home, the stadium is now not just an end in itself. It’s the beginning of something.

“Sports venues were once considered bad neighbors,” says Lee. “The American model was to move them outside the city, surrounded by parking garages. Now they are engines of urban renewal.”

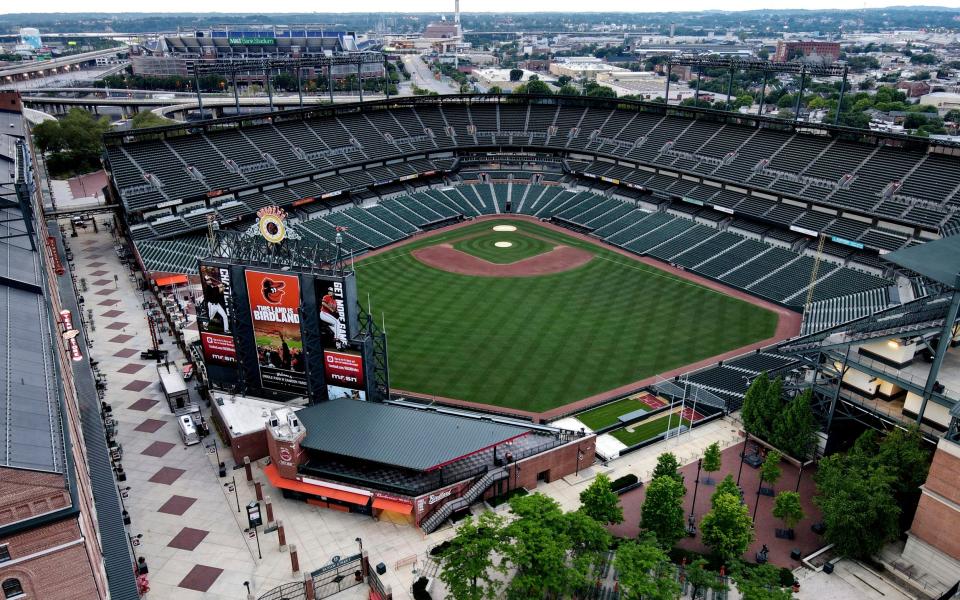

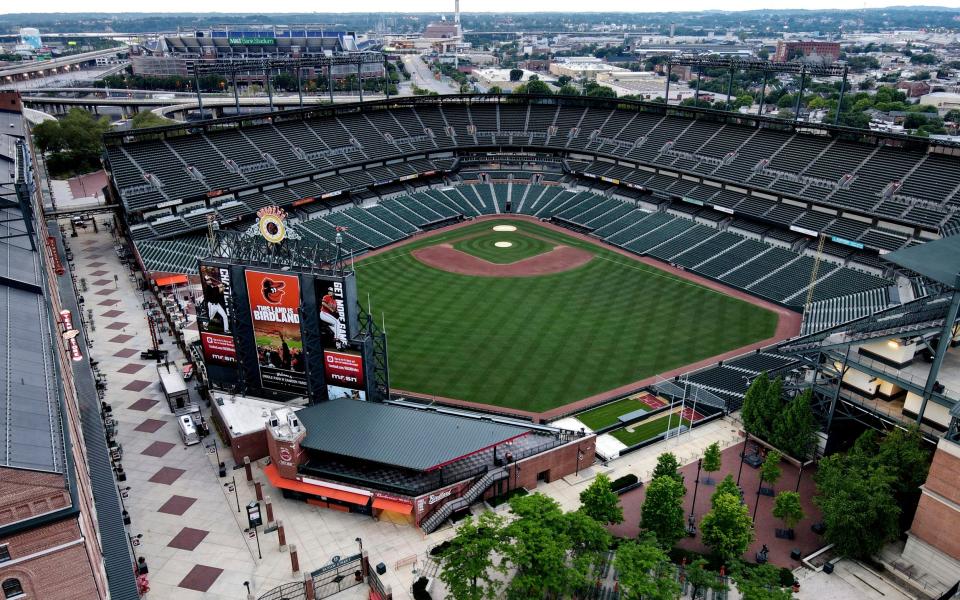

The first place to recognize that a stadium could be used to spur development was Baltimore, Maryland, when the new Orioles ballpark was built at Camden Yards; a neglected, post-industrial part of the city center.

“Since they moved there, the whole area has completely revitalized,” says Lee. “And you see that in this country. When we did the Emirates it was a crucial part of a plan to connect Lower Holloway to Islington; 4,500 new homes will be built around Spurs; Wembley is undergoing a massive redevelopment of what was a pretty sad area of disrepair.

However, whatever the wider implications for development, these buildings are the most important places for fans. And even there the accents have changed over the years.

“English football used to be guilty of seeing its spectators as a captive audience. You know ‘we’ll treat you how we want to treat you and you’ll still come back’,” says Lee. “The change over the last 30 years is that we recognize that fans are customers with choices.”

Although initially a certain category of fans was given priority.

“Yes, I admit that the emphasis in the beginning was mainly on company facilities. The big step at Spurs was to go from the least to the most expensive seat, we give you something.”

And at Spurs that is something substantial. Extensive food and drink halls, beautiful sight lines, reinforcement of the acoustics: everything to create an experience.

“The focus of the Tottenham Stadium design was on atmosphere, how to create identity in a seating bowl,” Lee explains. “Daniel Levy and I spent a lot of time traveling. We went everywhere and shamelessly borrowed things we liked. Not only to sports venues, but also to concert halls and theaters. There are little pieces from everywhere together in that building.”

Levy was hands-on in the process, sending a flurry of emails and anxious to make sure things were done as best as possible. Not least because of the stadium’s capacity: by channeling the energy of the North London derby, it had to accommodate more fans than the Emirates. Although Lee suggests the Spurs vice-chairman wasn’t the only client he had who was keen to be involved every step of the way.

“When we made the new Ascot stand [which opened in 2006], the queen was very practical. We had a monthly meeting with her where we showed progress on design and construction. She had so much input. And it always eases the planning process when the customer is the sovereign.”

The late queen was the Daniel Levy of Ascot: who knew?

As beautiful as it may be, even the Spurs Stadium is certainly not the end all be all. The innovation is relentless. Populous is building the new Coop Live indoor arena next to the Etihad in Manchester, incorporating modern acoustic engineering that will soon shape the design of outdoor venues. And then there’s the Sphere: the Las Vegas entertainment bowl that Lee and his colleagues designed.

“When we started, the necessary technology hadn’t even been invented yet,” he says of the state-of-the-art sound and lighting systems there. “And I think you saw at the recent Grand Prix in Vegas what that building can be.”

Indeed, it was the visual centerpiece of the race, with the cars spinning around what Lee describes as the largest billboard in the world. And the technical possibilities of the building point to a new future of sports viewing. Soon there could be Spheres all over the world, showing footage of live events in the most extraordinarily immersive way. As the North London derby takes place at the Tottenham Stadium, thousands of fans in Shanghai, Singapore and Saudi Arabia could watch things unfold in their local atmosphere, feeling as if they were are actually there.

“The truth is that the future of sports viewing will involve technology, lots of technology,” says Lee.

Well, that and heated seats.