As I push down the red airlock lever and step into our space station, I half wonder: Will I eventually lose my mind and be dragged out? After all, in the current popular television drama For All Mankind, one of the first astronauts to live on the moon for a long period of time does just that.

I’m not actually on the moon, of course, but instead confined to something called the Space Analogue for Moon and Mars (SAM) – a research center in the southern Arizona desert that boasts of being “as close as you can come’. to live on Mars without reducing gravity or dropping temperatures to 100 degrees Celsius below zero.” Same for the moon.

I’ll spend a week indoors, in a pressurized habitat intended to simulate missions beyond Earth and help us prepare for our first shaky steps as a multiplanetary species.

I’m a bit worried. I’ve been in extreme environments and know the price you can pay. Twenty years ago I lived in tents with scientists in Antarctica for a month. I began to suffer from insomnia, obsessiveness (I kept counting the remaining pairs of clean underwear), and finally severe depression. Before the expedition ended, I was evacuated by plane because I had suicidal thoughts.

Fortunately, this mission – called Imagination 1 – would go a lot better than that.

I lived in SAM with three artists—a poet, a textile designer, and a dancer—from the University of Arizona, where I had just retired as a creative writer. After all, if we want to make permanent homes in space, we will have to take our cultural life with us. For example, our dancer Liz George rehearsed movements for when she would put on a space suit during a simulated moonwalk. I took notes, planned articles and wrote daily mission reports.

But practical matters dominated, just like on the surface of the moon or the red planet. We monitored the CO2 level. We recycled our breath in the form of condensate into drinking water. We took turns cleaning the cozy 1,200-square-foot facility: the crew quarters, the equipment room, and the greenhouse module. We prepared dinner and dried the food scraps – ultimately to feed mushroom colonies for future ‘astronauts’ at SAM. We had to monitor and adjust the pressure maintenance system.

Our only contact was by email, as if we were in space, cut off from the rest of humanity, and we felt our isolation deeply.

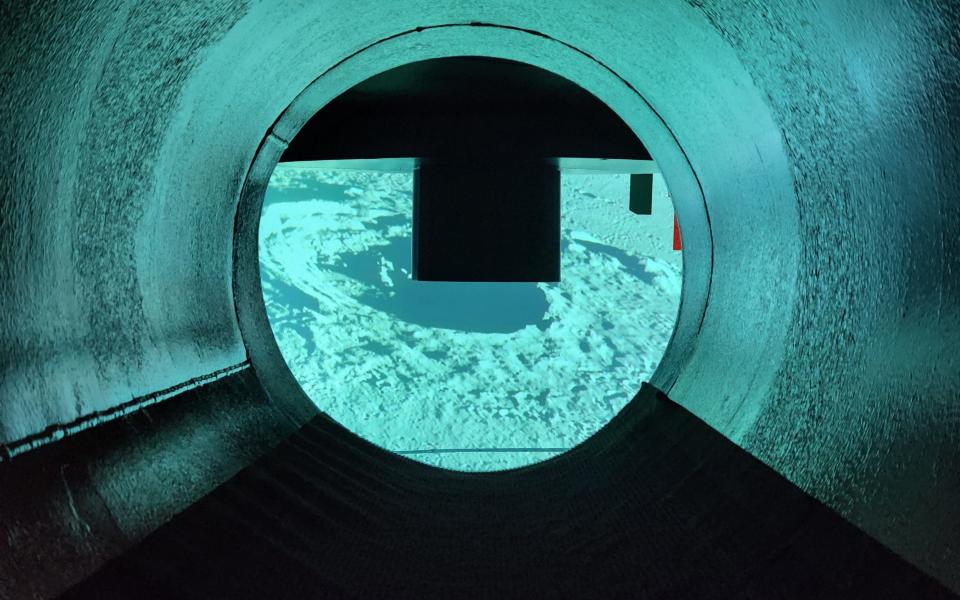

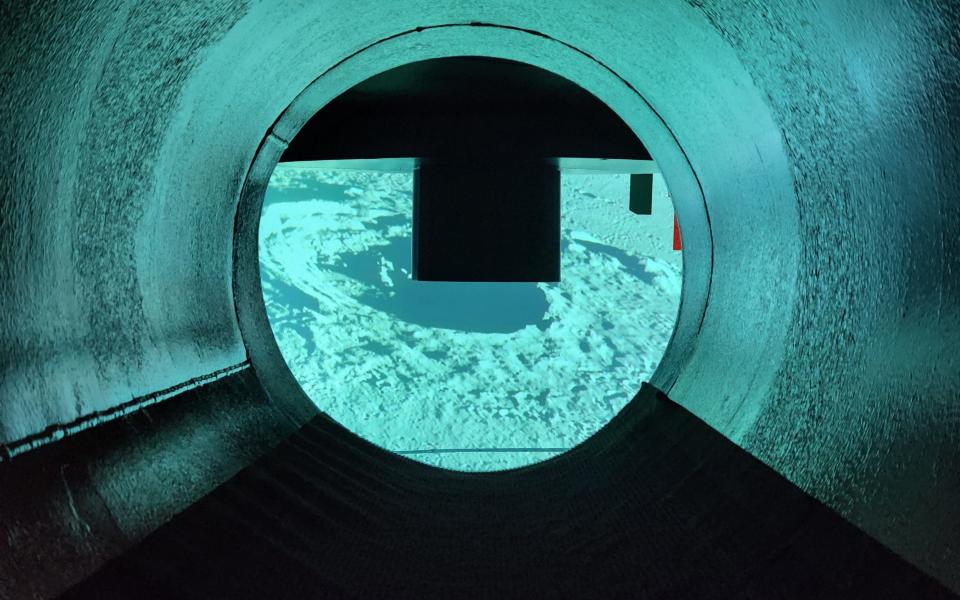

All this despite the pre-mission training, meeting several times before the “launch” and building a close-knit crew, which was essential because we worked on our projects from morning to night and on the maintenance of the high-tech systems from SAM. We even projected giant images of the moon onto the walls. Sometimes it really felt like we were there.

There were inevitably problems. Small groups in confined spaces experience poor sleep, along with stress that can lead to moodiness, moodiness, anxiety, mild to severe depression and even reduced dexterity. As the only man on the crew, I moved my sleeping mat from the crew quarters to under a plank in the Engineering Bay. Even that didn’t stop the women from hearing my disturbing snoring. The days were long with housework, from washing dishes with very little water to final checks of the air pressure and hydroponic rack before bed. We were tired. Small irritations can take on major proportions during confinement.

But to our credit, we handled the disruptions well. We checked on each other’s well-being. When one of us wanted space, the others remained quiet and distant. But if something had to be done, we told each other – and we didn’t back down. There wasn’t a single eye roll.

But add a few more weeks to Imagination 1 and that would certainly have changed. I know from my time in Antarctica that the extreme nature of such places can cause the ‘thousand meter stare’ and worse.

These are the challenges that the real astronauts of the Artemis program will face. NASA will send astronauts on a lunar flight later next year, followed by an actual landing with Artemis 3, scheduled for fall 2026. The crew will land on the moon’s dramatic, rugged south polar region, where water ice permanently lurks in the shadows. craters. The sun is low on the horizon and casts long light and longer shadows.

However, this is the mission that could usher in a new era of long-term exploration and science, because that ice could be turned into drinking water, air and rocket fuel.

The Artemis 3 crew will spend several days on the lunar surface, longer than any Apollo mission, and the vision (shared by China, which continues its own space missions) is for permanent “base camps” on the moon. Some of these may be underground, in empty lava tubes, protected from the many dangers of life on the moon.

The moon’s surface is buffeted by beams of radiation, from the sun and other stars, even other galaxies, particles traveling at the speed of near light that cut through living tissue that is not protected, severing DNA molecules like rice paper and ultimately leading up to cancer mutations. Long-term lunar residents could also suffer the lingering effects of long-term exposure to a sixth gravity. Lots of exercise will be needed to keep the heart, muscles and bone density strong.

Moondust is also a big problem. The post-1969 Apollo astronauts were annoyed by the acrid powder, which ended up under their fingernails and in their noses, lungs, mouth and eyes. Apollo 12’s Alan Bean said that residual dust in the lunar module cabin “made breathing difficult without a helmet, and there was enough particulate matter present… to affect our vision.”

Yet we will try to conjure up the green world from this gray land. In 2015 and 2016, Scott Kelly grew the first flowers in space: zinnias. He was absorbed by the sprouts, the leaves, the blossoms. Before astronauts on the International Space Station feast on lettuce leaves grown in hydroponic racks, they eat the sights, smells and textures of these memories of Earth. They will do exactly the same on the moon.

They will also create, as we did. Because as we came to the end of our week, it became clear to me that culture will become as essential in space as CO2 scrubbers, radiation shields and Moondust filters. If we don’t include creativity, our lives will become impoverished – both for the astronauts and for the rest of us who want to know what it’s like.

I was the last of the four people in the group to do a simulated moonwalk. As I put on my spacesuit, helped by my crewmates in the bulky, multi-layered garment, I further realized how difficult it is to be an astronaut. The fingertips of the gloves were large and rigid, but I still used them to press buttons on a camera. I remembered feeling claustrophobic in all my cold weather gear in Antarctica. The pressure suit was much more restrictive. After mounting my helmet, the air flowed past my ear like a steady river. In a partially landscaped industrial garden, I walked in wide, galloping steps while attached to a counterweight system that simulated the moon’s gravity.

It felt a little uncomfortable at first, but then, toe by toe, with my arms wide as if I were floating, I got used to this new effect on my body. I wasn’t exactly graceful, but I was smiling. As a 60-year-old child of Apollo and amateur astronomer, I knew this was as close to the moon as I could ever get.