Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific developments and more.

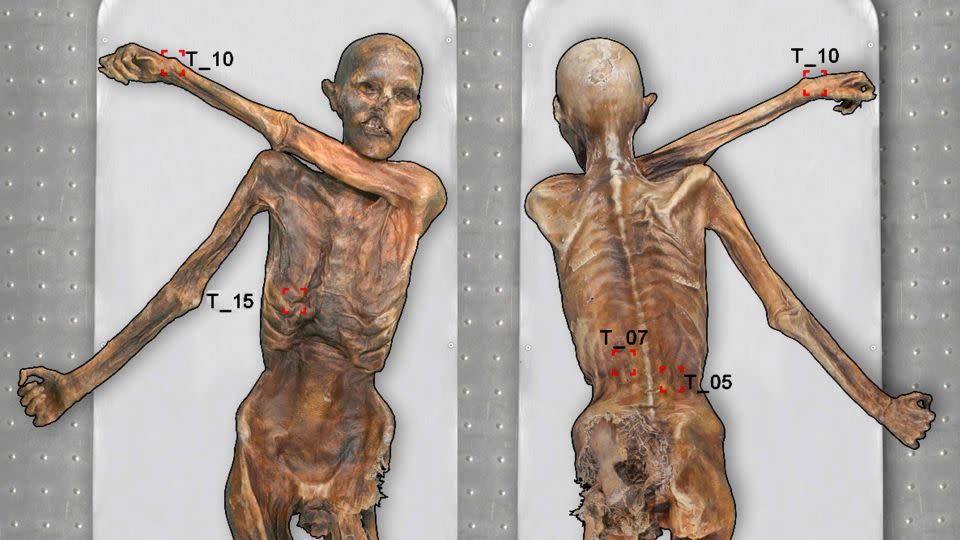

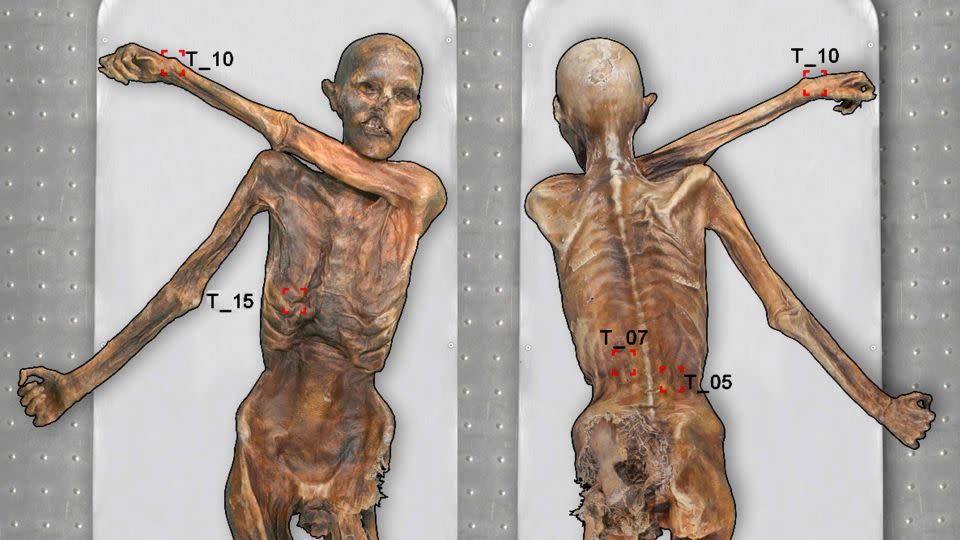

Ötzi the Iceman was found high in the Tyrolean Alps in 1991 and had dark skin and eyes and was probably bald. His remarkably well-preserved remains, frozen beneath the ice for about 5,300 years, revealed 61 tattoos inked all over his body.

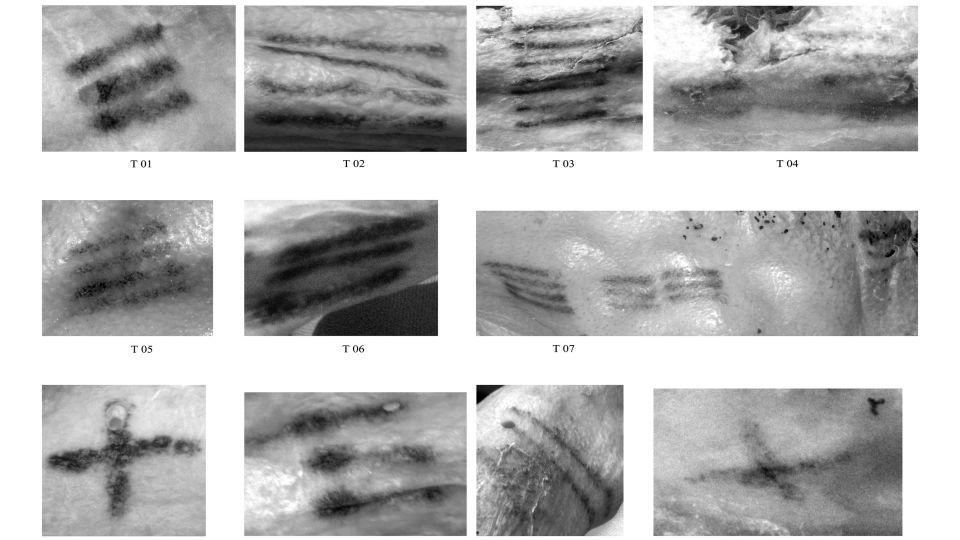

How and why Ötzi, perhaps the most studied corpse in the world, came to be the body art has long been a source of fascination. Initial analysis showed that the tattoos had been incised with a knife and then impregnated with black pigment. Now the latest research strongly suggests that a single-point lancing instrument, fitted with a carbon-pigmented tip, could have been behind the markings.

“One of the points we identified is that a lot of the work done on his tattoos was initially done by scientists who were excellent scientists, but who were not tattooed themselves and had no personal experience with tattooing,” said Aaron. Deter-Wolf, lead author of the new study.

“Over the years I’ve had countless conversations with professional tattoo artists and when you talk about them and look at the pictures, they say, oh, no, oh, no, they definitely weren’t cut into the skin… but they weren’t. “It hasn’t been shown in a scientifically sound environment,” explains Deter-Wolf, a prehistoric archaeologist with the Tennessee Division of Archeology, who has a tattoo on his wrist similar to Ötzi’s.

The study, published in the European Journal of Archeology on March 13, reviewed existing literature on Ötzi’s tattoos and drew on contemporary experiments replicating ancient tattooing techniques.

“Most were on the lower legs and ankles. One on the left wrist and a couple on the lower back around the cervical spine,” Deter-Wolf said.

“These are lines that are sometimes crossed, but more often parallel to each other. They range from two (lines) to five or six.”

Scientists have analyzed almost every part of Ötzi and his belongings, painting an intimate picture of life at the end of the fourth millennium BC. And now the new study offers a better understanding of how the oldest known tattoos in human history came to be, although questions still remain about the meaning behind the body art.

A scientific celebrity

Originally, researchers thought Ötzi froze to death, but a 2001 X-ray revealed an arrowhead in his shoulder, which would have been fatal. The iceman also had a head wound, possibly suffered at the same time, and his right hand shows a defensive wound.

The mystery of Ötzi’s violent death, who he was and how he ended up on a mountain pass, has sparked interest far beyond archaeology. Every year thousands visit his mummified remains, which are on display at the South Tyrolean Archaeological Museum in Bolzano, Italy.

The existing scientific knowledge about Ötzi is astonishingly comprehensive. Stomach contents provided information about his last meal and where he came from, examination of his DNA has revealed his origins and appearance, his weapons showed he was right-handed and his clothing provided a rare glimpse into what ancient people actually wore.

In a February 2016 study, Deter-Wolf compiled a database of dozens of examples of ancient tattoos, including body art found on mummified remains from Egypt, China and the Incas, identifying Ötzi’s body art as the oldest known examples of tattoos. This feat was possible thanks to non-destructive digital imaging technology and collaborations between archaeologists and tattoo artists.

“If we all put our heads together, we’ll come up with a much better and more informed hypothesis about how these things work,” he said.

The 2016 study suggests that tattoos are a long-standing and widespread cultural practice, with various ways of permanently placing pigments under the skin. The techniques include hand poking or tapping using a single-point tool that may or may not have a handle; incision; and subdermal tattooing, or skin suture, which uses a needle to thread an ink-soaked filament or tendon.

Deter-Wolf and his colleagues also experimented with several traditional techniques in a September 2022 study. Using eight tools made from animal bone, obsidian, copper and boar’s tooth, along with a modern steel needle, New Zealand-based traditional tattoo artist and study co-author Danny Riday inked tattoos on his leg .

The tattoos on Ötzi’s body have rounded edges that resemble a hand-poked tattoo, most likely made with bone or copper, Deter-Wolf said. Incision tattoos, on the other hand, create edges that are pointed due to the way the lines are cut into the skin.

“There’s a variation within the line because you put all these individual punctures so close together and the degree to which they overlap results in a kind of stippling effect when you look at it with enough magnification.”

A bone awl that Ötzi carried in his toolbox was a potential candidate, but has yet to be studied in detail to confirm whether microscopic wear marks are consistent with a tattoo function. However, Deter-Wolf thinks this is unlikely.

“It is highly suggestive in (the) context (of a) lumberjack outfit rather than a tattoo kit.”

The new knowledge of how Ötzi’s tattoos were likely made was “particularly exciting” because the piercing method used showed continuity with contemporary tattooing techniques, said Dr. Matt Lodder, associate professor of art history and theory, and director of American Studies. at the University of Essex in Great Britain.

“The real magic of Ötzi’s story for modern eyes is how familiar it feels – anyone who has been tattooed, especially if you have been tattooed with hand tools, can identify with the sensations he would have felt while being tattooed, the process he went through to heal his tattoos,” says Lodder, who is also the author of “Painted People: Humanity in 21 Tattoos.” He was not involved in the investigation.

“That we can empathize so deeply with a man who lived five millennia ago is a remarkably powerful link to our shared human past.”

Unsolved mystery of Ötzi’s tattoos

Why did Ötzi have so many tattoos? One explanation put forward in the scientific literature is that it was an ancient healing technique, somewhat similar to an early form of acupuncture, rather than body art. Many of the tattoos could have been an age-old way to treat joint pain in his lower back, knees, hip and wrists.

“We don’t disagree with the idea that they could have been therapeutic. I think it’s all on the table. Just because something has given us therapeutic treatment doesn’t mean it doesn’t have cultural symbolic value,” Deter-Wolf said.

Marco Samadelli, a senior researcher at the Institute for Mummy Studies of Eurac Research, a private research institute in Bolzano, said the work was of a “high scientific standard.”

“The authors do not claim with absolute certainty the technique of piercing tattoos with a single-pointed instrument, but provide extensive and plausible explanations,” he said via email.

Samadelli urged the team to continue their investigation into Ötzi’s tattoos and how they were made.

‘To date there are no plans to examine the bone awl and horn tooth found on the Iceman to see if they were used as hand tools, but I hope Aaron Deter-Wolf will maintain his interest and submit an application to the scientific committee from the Ötzi Museum to analyze and study them.”

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com