Scientists are sounding the alarm as a crucial part of the planet’s climate system is gradually deteriorating and could one day reach a tipping point that would radically change global weather patterns.

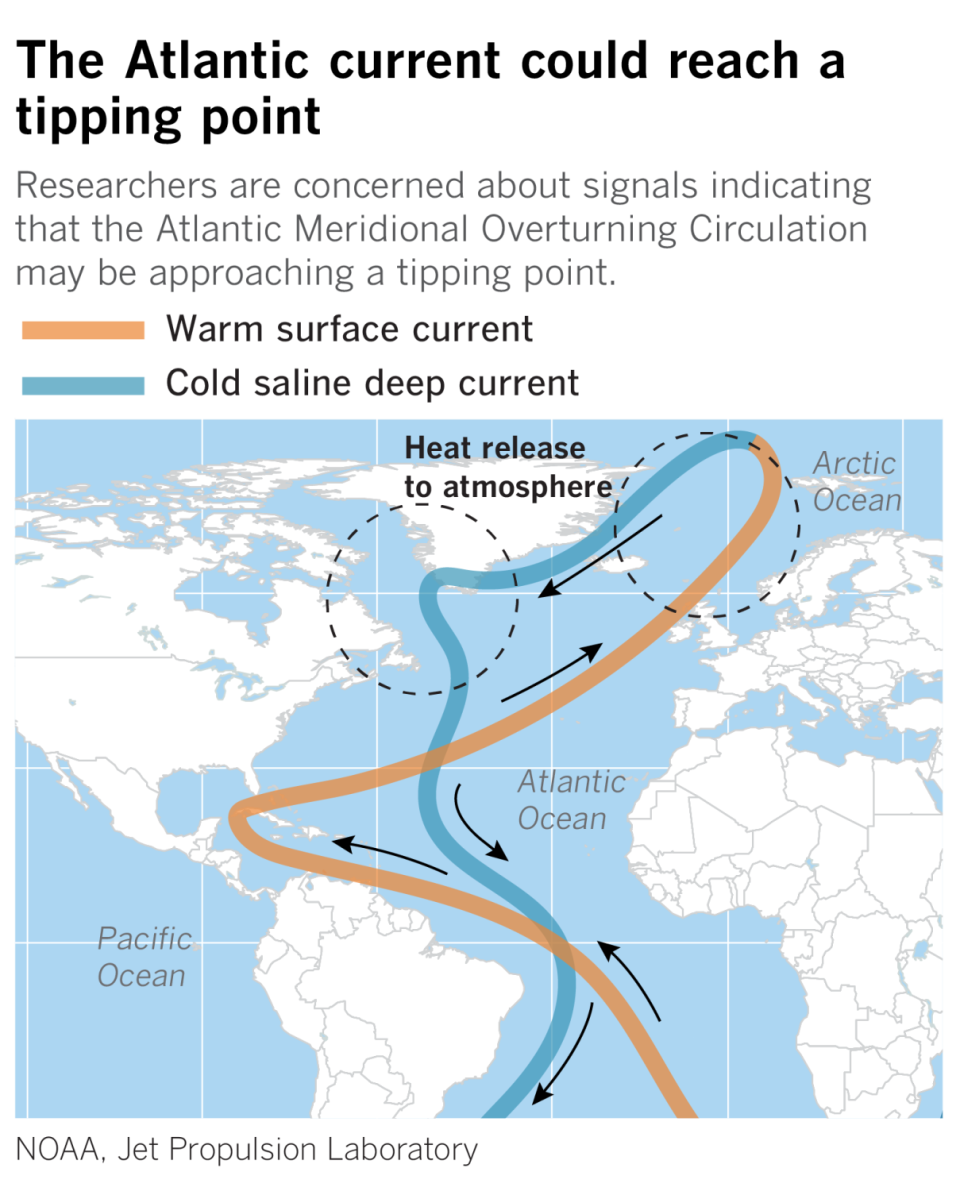

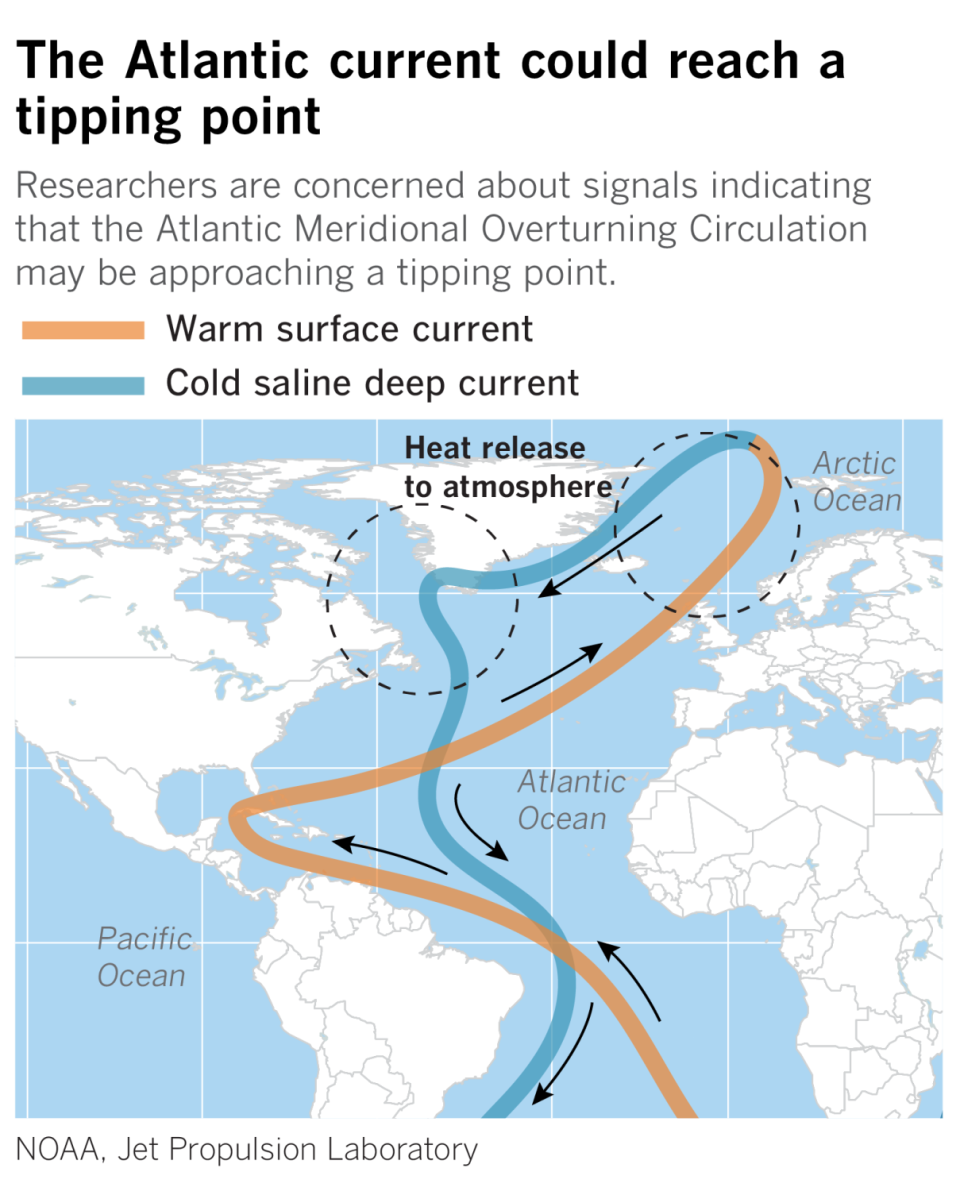

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, is a system of ocean currents that circulate water in the Atlantic Ocean like a conveyor belt, redistributing heat and regulating global and regional climate. However, new research warns that the AMOC is weakening under a warming climate, and could potentially undergo a dangerous and abrupt collapse with global consequences.

“This is bad news for the climate system and humanity,” researchers from the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research at Utrecht University wrote in a new study published in the journal Science Advances.

Since the AMOC is the workhorse of the Atlantic Ocean, the consequences of such a collapse would result in “massively chaotic changes in global weather patterns” that extend well beyond the Atlantic Ocean, said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA who did not was involved in the study.

“It would essentially plunge Europe into a regionalized ice age, while leaving the rest of the world on a continuing warming path,” Swain said. “The Southern Hemisphere would decay, the Pacific storm track would go crazy, and there would be extreme shifts in weather patterns that are very different from what you would expect from a more incremental or linear warming path.”

The chance of such a collapse is small — about 5% or 10% this century, according to some researchers — but the consequences are so great that it would be unwise to ignore the possibility, Swain said.

“There’s one more [90%] up to a 95% chance that won’t happen, but would you be willing to bet the farm on one [90%] to a 95% chance that something like that won’t happen?,” he said. “Would you get on a plane if there was one [90%] up to a 95% chance it won’t crash? I certainly wouldn’t do that.”

Read more: La Niña on the horizon? California’s wild weather year could get even stranger

The AMOC moves water in the Atlantic Ocean in a long cycle from north to south and back again, but there is evidence that it has weakened over the past century, including a decline of about 15% since 1950.

The system depends on a delicate balance between warm surface water and cold, salty water that sinks to the seabed, which together maintain the current. But as the planet warms, melting glaciers and ice sheets – such as the Greenland Ice Sheet – add more freshwater to the system, reducing salinity and disrupting traditional patterns.

“It’s a self-reinforcing feedback loop that mainly affects salinity, and the fresher the North Atlantic gets, the weaker the AMOC, until you reach a critical value,” said René van Westen, lead author of the study.

The study does not indicate a time frame for when such a collapse could occur, and Van Westen said such estimates could be controversial. But the paper was the first to show that the AMOC can reach a tipping point if enough freshwater is added to the system.

“There is still intense debate about whether this is a possibility in the 21st century, but we cannot rule it out at this time,” he said.

A similar scenario played out in the movie “The Day After Tomorrow,” although experts said the events in that movie, which take place over the course of a few days, are heavily dramatized.

Read more: As climate dangers converge, more and more Californians are living in danger

Dutch researchers say models indicate an AMOC collapse is possible, and that such an event would significantly change the planet’s climate. The impacts would be most acute in Europe, where temperatures could drop to 18 degrees on average, or as high as 36 degrees in places like Norway and Scandinavia. It could also lead to ‘see-saw’ conditions between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Other potential impacts include rapidly rising sea levels, with sea level rises of more than 60 cm possible along some coastal areas, including the Netherlands and the east coast of the US. New York City could be swamped by as much as 30 inches of sea level rise, Van Westen said.

The Amazon rainforest would see its dry and wet seasons reverse, potentially leading to its own tipping point. (A separate study published this month found that parts of that rainforest could collapse as early as 2050.)

The impacts on the Pacific Ocean and the U.S. West Coast would likely be smaller because of their distance from the Atlantic Ocean, Van Westen said. However, his models show that a collapse of the AMOC could result in reduced precipitation and slight cooling in Los Angeles, which would compete with the larger signal of climate change toward regional warming.

In fact, the possible future collapse of the AMOC is in some ways a different scenario from the effects of climate change already occurring, says Swain of UCLA. Currently, climate change is mainly amplifying known pre-existing patterns and risks, such as worsening wildfires in California, or more extreme downpours and floods.

“But a collapse of the global overturning circulation would be really different, because it would result in realignments of the jet stream, of the storm track, of which places on Earth are very cold compared to other places,” he said.

The jet stream — the river of air that moves storms eastward around the world — often helps send atmospheric rivers toward California.

Such disruptions would not only affect climate and temperature conditions, they would also erode the fabric of civilization. Agriculture in Europe would likely come to a standstill, while coastal cities would experience major problems from flooding. Building codes and infrastructure could become outdated as seasonal and precipitation patterns quickly turn warm places into cool places, and vice versa.

“It would mean that all the climate adaptation we’re working on now wouldn’t necessarily be the climate we would experience,” Swain said.

Read more: The planet is dangerously close to this climate threshold. This is what 1.5°C really means

Other experts said some of the scenarios outlined in the study are at the extreme end of what is plausible. The model required exceptional amounts of freshwater flow into the Atlantic Ocean to trigger the tipping point — an amount equivalent to about seven Greenland ice sheets — according to Josh Willis, an oceanographer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge.

“It is still possible that the overthrow will stop, and if it does, it will have major consequences,” Willis said. “But it is not immediately one meter sea level and immediately a cooling of 15 degrees Celsius. It is not ‘the day after tomorrow’.”

Still, Willis said the system may be more sensitive than previously thought, and that future models and simulations could add to the growing body of work. Other recent studies have also warned of an impending collapse of the AMOC and of a possible collapse of the Antarctic Ocean current.

“It’s an interesting study,” he said of the latest paper, “and the AMOC could still show that it can be closed. But this study isn’t necessarily conclusive on that. There are still a lot of questions open.”

Lynne Talley, a distinguished professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, similarly said there is “natural variability” in the AMOC, which can include both strengthening and weakening on a timescale of about ten years. -term trend.

However, she said the research into its possible collapse is compelling and worth considering.

“First of all, it’s possible…I wouldn’t shy away from saying that,” she said.

Research on salinity is particularly valuable, she added, because salinity helps determine the density of water in the AMOC. A similar mechanism may have caused the AMOC crash at the end of the last ice age, about 14,000 years ago.

At the time, the melting of the North American ice sheet was sending a lot of freshwater into the North Atlantic Ocean, “and that obviously slowed it down and it kind of stopped,” Talley said.

“I find it completely plausible that it would crash at some point, and the control is salty,” she said. “But what year does that happen? I don’t know.”

Such a collapse would likely be irreversible – at least over any timescale relevant to a human lifetime. But there are safeguards to prevent such a collapse: namely reducing emissions of methane, carbon dioxide and other fossil fuels that are warming the planet, melting ice and releasing more fresh water into the ocean.

“That’s really the answer to everything,” Talley said. “I think we need to protect ourselves from a lot of things regarding climate change, and this is one of the big ones for the Northern Hemisphere.”

This story originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times.